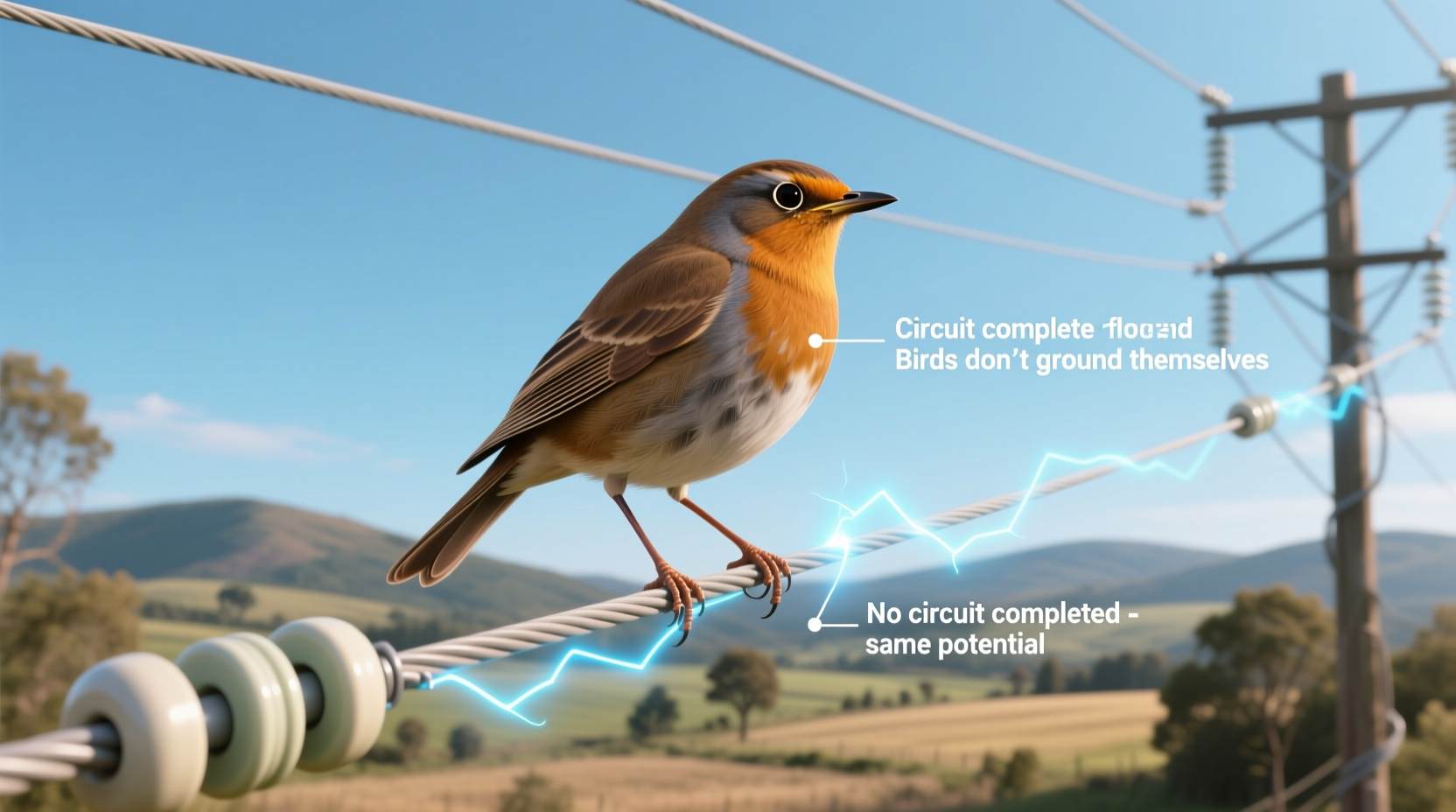

Birds don't get electrocuted on power lines because they do not complete an electrical circuit. When a bird lands on a single power line, its body is at the same electrical potential as the wire, and since electricity always seeks the path of least resistance to the ground, no current flows through the bird’s body—this phenomenon explains why don’t birds get electrocuted on power lines. As long as the bird doesn’t touch another wire or a grounded object like a pole or tree, it remains safe from electric shock. This basic principle of electrical conductivity and grounding is central to understanding avian safety around high-voltage infrastructure.

The Science Behind Why Birds Don’t Get Electrocuted

Electricity travels along conductive paths, moving from areas of high voltage to low voltage, typically toward the ground. For a creature to be electrocuted, there must be a difference in electrical potential across its body—meaning one part of the body must contact a high-voltage source while another contacts a lower voltage point or the ground. This creates a circuit, allowing current to flow through the organism.

Birds perched on a single power line are only in contact with one electrical potential. Their feet are close together on the same wire, so there's minimal voltage difference between them. Because their bodies offer higher resistance than the copper or aluminum wire, electricity continues along the path of least resistance—the wire itself—bypassing the bird entirely. This is why small birds like sparrows, starlings, and swallows can sit on live wires without harm.

When Birds *Can* Get Electrocuted: The Danger of Contacting Multiple Wires

While sitting on one wire is safe, birds can—and sometimes do—get electrocuted when they bridge two wires at different voltages or touch a live wire and a grounded structure simultaneously. Large birds such as eagles, hawks, owls, and vultures are especially vulnerable due to their wide wingspans. If a raptor takes off or lands and its wingtip touches a second wire or a transformer while one foot remains on the live wire, it creates a short circuit through its body, resulting in fatal electrocution.

This risk is particularly high on older utility poles that lack proper insulation or spacing. In fact, electrocution is a leading cause of death for some endangered raptors, including the golden eagle and the California condor. Power companies in many regions have begun retrofitting poles with wider spacing, insulated covers, and perch deterrents to reduce avian fatalities.

Biological Factors That Help Protect Birds

Birds also possess certain biological traits that contribute to their safety on power lines. Their feet are covered in dry, scaly skin with relatively high electrical resistance. Unlike mammals with moist skin or sweat glands, birds do not easily conduct electricity through their extremities. Additionally, most small birds have lightweight bodies and minimal contact area with the wire, further reducing the chance of current flow.

It’s important to note that feathers play no direct role in insulating against high voltage. While feathers are excellent thermal insulators, they offer little protection against electrical currents—especially if damp or soiled. The real safeguard lies in the bird’s behavior and positioning, not its plumage.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Birds on Wires

Beyond biology and physics, birds lined up on power lines have captured human imagination across cultures. To some, they symbolize unity, communication, or even surveillance—silent observers of the modern world. In photography and film, flocks on wires often represent transition, freedom, or urban isolation. Artists and poets have likened them to musical notes on a staff, evoking rhythm and harmony in otherwise chaotic cityscapes.

In various spiritual traditions, birds perched high above the ground are seen as messengers between realms—the earthly and the divine. Their ability to rest safely on man-made structures carrying invisible energy may subtly reinforce this symbolism. While these interpretations are metaphorical, they reflect a deep human fascination with how nature adapts to technological landscapes.

Practical Implications for Utility Companies and Conservationists

Understanding why birds don’t get electrocuted on power lines isn’t just a scientific curiosity—it has real-world applications. Wildlife biologists and electrical engineers collaborate to design bird-safe infrastructure, especially in ecologically sensitive areas. Measures include:

- Installing perch discouragers (spikes or rotating devices) on dangerous parts of poles

- Using insulated cables or covering exposed connectors

- Increasing separation between energized components

- Placing raptor nesting platforms away from hazardous equipment

These modifications are cost-effective and significantly reduce avian mortality. In the U.S., the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and Endangered Species Act provide legal incentives for utilities to adopt bird-friendly practices.

| Bird Type | Risk Level on Power Lines | Main Risk Factor | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small songbirds (e.g., finches, robins) | Very Low | Rarely span multiple conductors | Minimal intervention needed |

| Pigeons and crows | Moderate | Nest on poles; may contact grounded parts | Insulate transformers; discourage nesting |

| Raptors (eagles, hawks, owls) | High | Wide wingspan bridges conductors | Wider spacing; perch management |

| Waterfowl (herons, cranes) | Moderate to High | Long legs and necks increase contact risk | Elevate lines; use markers |

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Electricity

Several myths persist about birds and power lines. One common belief is that birds are immune to electricity due to special insulation in their bodies. This is false—birds are not electrically insulated by nature. Another misconception is that all birds avoid power lines. In reality, many species prefer them as vantage points for hunting or resting due to unobstructed views and warmth radiating from transformers.

Some people assume that if a bird can sit on a wire, it must be de-energized. This dangerous assumption can lead to accidents during maintenance work. Always assume power lines are live unless confirmed otherwise by utility professionals.

Tips for Observers and Birdwatchers

If you're a birder or nature enthusiast, here are practical tips for safely observing birds on power lines:

- Use binoculars or a spotting scope to observe behavior without disturbing the birds or approaching dangerous areas.

- Avoid photographing near substations or transformers, which pose risks to humans and may be restricted zones.

- Report injured or dead birds near power lines to local wildlife rehabilitators or utility companies—they may indicate unsafe conditions.

- Learn to identify high-risk species like eagles or great blue herons that may be more prone to electrocution.

- Support conservation initiatives that promote avian-safe utility designs in your community.

Regional Differences and Infrastructure Design

Safety standards for power lines vary globally. In rural areas of developing countries, overhead lines are often older, less insulated, and more densely packed, increasing the risk to birds. In contrast, European and North American utilities increasingly follow avian protection guidelines set by organizations like the Avian Power Line Interaction Committee (APLIC).

In desert regions where large raptors are common, such as the southwestern United States, special mitigation efforts are underway. Solar farms and wind installations in these areas often include avian monitoring programs to prevent collisions and electrocutions.

What Happens When a Bird Dies on a Power Line?

Occasionally, a bird may die on a wire due to illness, predation, or electrocution. If the carcass remains on the line, it usually dries out and eventually falls off due to wind or scavengers. Utility workers typically remove animal remains during routine inspections, especially if they pose a fire hazard or cause power fluctuations.

Unlike rodents or squirrels—which frequently cause outages by bridging connections—birds rarely disrupt service unless they are large enough to create a short circuit. Even then, modern grid systems often have automatic breakers that minimize damage.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why don’t birds get shocked on power lines but humans would?

- Humans are usually grounded (via feet on earth or ladders), so touching a live wire creates a circuit. Birds aren’t grounded, so no current flows through them.

- Can baby birds get electrocuted on power lines?

- Yes, if they fall and flap between wires or from a wire to a pole. Juvenile birds exploring near nests on poles are at higher risk.

- Do all types of birds sit on power lines safely?

- Most small birds do, but large birds with wide wingspans—like eagles and owls—are at risk if they touch multiple conductors.

- Is it dangerous to stand under a power line where birds are perched?

- No, the presence of birds doesn’t increase danger. However, never approach downed lines—even if birds seem unaffected.

- How can we make power lines safer for birds?

- By insulating connections, increasing spacing between wires, installing perch deterrents, and relocating nests away from hazards.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4