A large bird is not a mammal; it is a member of the class Aves, characterized by feathers, beaks, and the ability to lay hard-shelled eggs. One of the most iconic examples of a large bird is the ostrich, which stands as the tallest and heaviest living bird species in the world. When people search for information about whether birds are mammals or what defines a large bird, theyâre often trying to understand the biological distinctions between animal classes while also exploring the cultural significance and observable traits of prominent avian species. This article will explore the biology of large birds, their ecological roles, symbolic meanings across cultures, and practical tips for observing them in the wildâoffering a comprehensive answer to questions surrounding a large birdâs place in nature and human society.

Defining Characteristics of Large Birds

Large birds share several defining biological features that distinguish them from mammals and smaller avian species. These include powerful skeletal structures adapted for weight support, advanced respiratory systems with air sacs, and high metabolic rates. Unlike mammals, birds are warm-blooded vertebrates that reproduce by laying eggs and lack mammary glands. The term a large bird typically refers to species exceeding four feet in height or weighing over 20 pounds. Notable examples include the common ostrich (Struthio camelus), the southern cassowary, the emu, and the Andean condor.

Ostriches, native to African savannas and deserts, can reach up to 9 feet tall and weigh over 300 pounds. They possess long legs built for speedâcapable of sprinting at 45 miles per hourâand have only two toes on each foot, an adaptation for running. Despite their size, ostriches cannot fly due to their heavy bodies and underdeveloped wing muscles. Instead, they use their wings for balance, courtship displays, and shade provision.

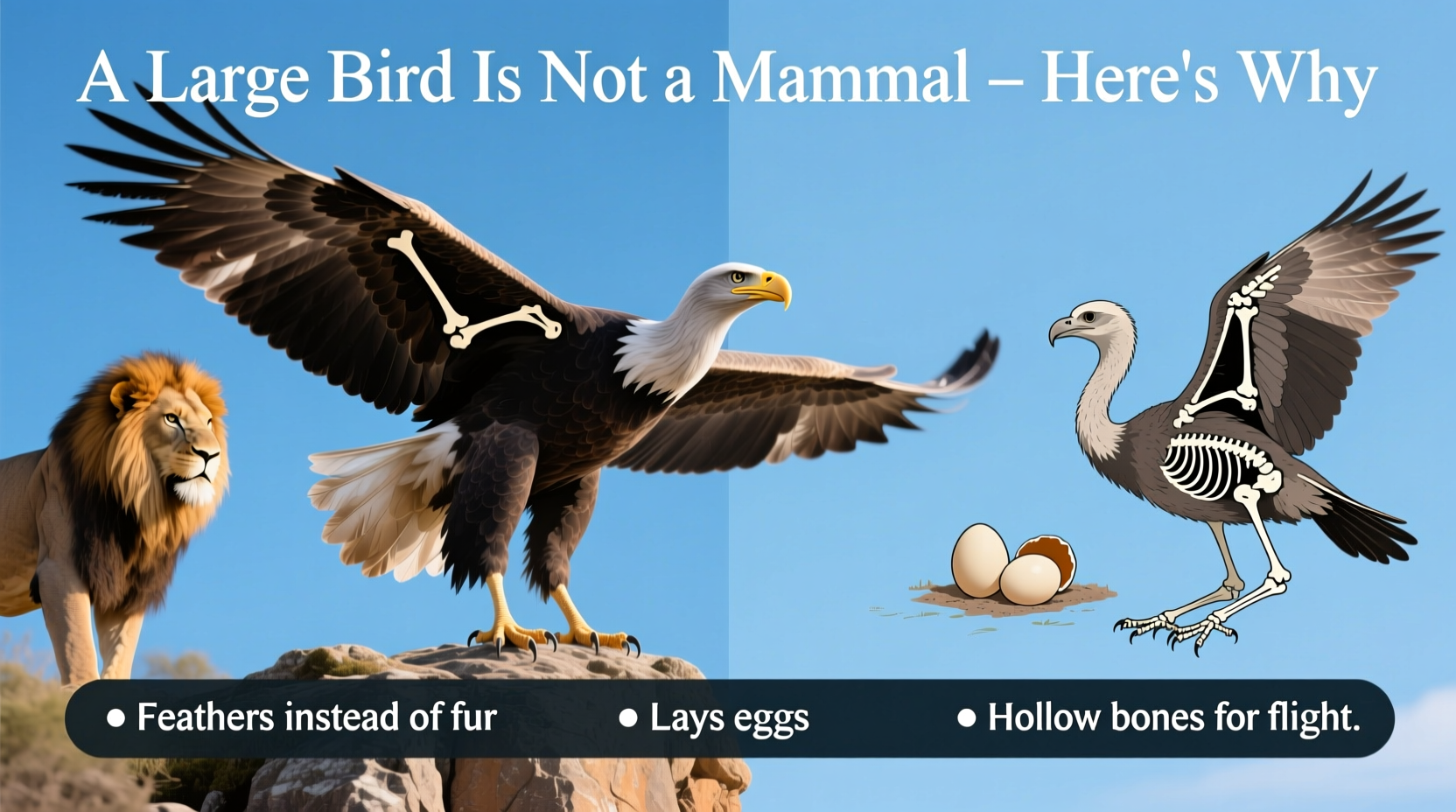

Biological Classification: Why a Large Bird Is Not a Mammal

One of the most common misconceptions involves confusing large flightless birds like ostriches with mammals due to their ground-dwelling habits and substantial size. However, taxonomically, all birdsâincluding a large bird such as the emu or rheaâare part of the clade Avialae, which evolved from theropod dinosaurs. Key differences between mammals and birds include:

- Reproduction: Birds lay amniotic eggs with calcified shells; mammals mostly give birth to live young (except monotremes like the platypus).

- Body Covering: Birds have feathers; mammals have hair or fur. \li>Feeding Young: Birds feed offspring via regurgitation or direct provisioning; mammals nurse using milk produced by mammary glands.

- Skeletal Features: Birds have hollow bones and a keeled sternum for flight muscle attachment (even if flightless); mammals have denser bones and no keel.

These distinctions firmly place a large bird within Aves, not Mammalia.

Habitat and Distribution of Major Large Bird Species

Different large bird species occupy distinct ecological niches across continents. Understanding their habitats helps explain their evolutionary adaptations and informs conservation efforts. Below is a comparative overview:

| Species | Native Region | Average Height | Average Weight | Conservation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Ostrich | Sub-Saharan Africa | 7â9 ft | 200â300 lbs | Least Concern |

| Emu | Australia | 5â6 ft | 60â90 lbs | Least Concern |

| Southern Cassowary | New Guinea, Australia, Indonesia | 5â6 ft | 70â130 lbs | Vulnerable |

| Andean Condor | South American Andes | 4â5 ft | 20â33 lbs | Vulnerable |

| Greater Rhea | Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia | 4â5 ft | 40â88 lbs | Near Threatened |

While some large birds thrive in open grasslands (ostriches, rheas), others inhabit dense tropical forests (cassowaries) or mountainous regions (condors). Their distribution reflects dietary needs, predation pressures, and climate adaptability.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Large Birds

Beyond biology, a large bird often carries deep symbolic meaning in human cultures. In ancient Egypt, the ostrich feather was a hieroglyph representing truth and justiceâMaâat, the goddess of order, wore one. Pharaohs used ostrich fans in ceremonial processions, symbolizing divine authority. Similarly, among the Maasai of East Africa, ostrich feathers signify bravery and social status.

In Aboriginal Australian traditions, the emu plays a central role in Dreamtime stories. The constellation now known as the Southern Cross is interpreted as part of an emu in the sky, linking celestial patterns to terrestrial animals. Emu tracks also appear frequently in rock art, indicating spiritual reverence.

The Andean condor holds sacred status among indigenous peoples of the Andes. In countries like Peru and Ecuador, it symbolizes power, freedom, and a connection between Earth and the heavens. It appears on national emblems and is protected by law in several South American nations.

Ecological Roles of Large Birds

Large birds serve vital functions in ecosystems. As scavengers, condors help prevent disease spread by consuming carrion. Their highly acidic digestive systems neutralize dangerous pathogens like anthrax and botulism. In contrast, seed-dispersing species like the cassowary are called ârainforest gardenersâ because they swallow fruit whole and excrete viable seeds over wide areas, promoting forest regeneration.

Ostriches, though primarily herbivorous, influence vegetation patterns through grazing and trampling. Their nesting behaviorâshallow scrapes in soilâcan create microhabitats for insects and small reptiles. Predators such as lions and hyenas rely on ostrich eggs as seasonal food sources, highlighting the interconnectedness of species.

Threats Facing Large Birds Today

Despite their resilience, many large bird species face significant threats. Habitat loss due to agriculture, urban development, and logging is the primary danger. For example, the southern cassowaryâs rainforest habitat in Queensland, Australia, has been reduced by over 80% since European settlement.

Human-wildlife conflict also poses risks. Ostriches may wander into farmland, leading to culling or capture. Vehicle collisions are a growing cause of mortality, especially in areas where roads cut through migratory corridors. Poaching remains an issueâfor feathers, meat, or traditional medicineâparticularly in regions with weak enforcement.

Climate change affects food availability and breeding cycles. Rising temperatures alter fruiting seasons, disrupting the feeding schedules of frugivorous birds like the cassowary. Droughts reduce water access for ground-dwelling species, increasing competition and stress.

How to Observe Large Birds in the Wild: Practical Tips for Birdwatchers

Observing a large bird in its natural environment is a rewarding experience for amateur and expert ornithologists alike. To maximize your chances of sightings while minimizing disturbance, follow these best practices:

- Research Local Habitats: Identify regions where target species live. Use resources like eBird or IUCN Red List maps to locate recent sightings of a large bird such as the Andean condor or greater rhea.

- Visit During Optimal Seasons: Many large birds have predictable breeding or feeding patterns. For instance, condors soar more frequently during thermal-rich mornings in dry seasons when carcasses are easier to spot.

- Use Appropriate Gear: Binoculars with 8x42 magnification or spotting scopes enhance visibility without requiring close approach. Wear neutral-colored clothing to avoid startling animals.

- Maintain Distance: Always respect wildlife boundaries. Approaching too closely can provoke defensive behaviorsâespecially in cassowaries, which are known to kick aggressively when threatened.

- Follow Local Guidelines: National parks and reserves often have specific rules for viewing large birds. Check official websites before visiting to ensure compliance with trail restrictions or seasonal closures.

In North America, visitors to Arizonaâs Grand Canyon may see California condors released through reintroduction programs. In Australia, guided tours in Daintree Rainforest offer safe cassowary viewing opportunities. African safaris in Namibia or Kenya provide excellent ostrich observation in semi-arid plains.

Debunking Common Misconceptions About a Large Bird

Several myths persist about large birds, often stemming from folklore or incomplete understanding. Letâs clarify three prevalent ones:

- Myth: Ostriches bury their heads in the sand. Reality: When alarmed, ostriches lower their long necks to the ground to blend in visually. From a distance, this looks like head-burying, but they are actually camouflaging themselves.

- Myth: All large birds are flightless. Reality: While ostriches, emus, and cassowaries cannot fly, the Andean condor is a master glider, capable of soaring for hours without flapping its wings. Its wingspan exceeds 10 feet.

- Myth: Large birds are aggressive toward humans. Reality> Most are shy and avoid contact. Exceptions occur during nesting season or when provoked. Cassowaries deserve caution, but attacks are rare and usually involve habituated individuals near human settlements.

Conservation Efforts and How You Can Help

Protecting a large bird requires coordinated global action. Successful initiatives include captive breeding, habitat restoration, and legal protections. The California condor recovery program, launched in the 1980s when only 27 individuals remained, increased populations to over 500 today through zoo-based breeding and careful release strategies.

You can contribute by supporting organizations like BirdLife International, the World Parrot Trust, or local sanctuaries. Avoid purchasing products made from wild bird parts, and advocate for road signage in critical habitats to reduce vehicle strikes. Participating in citizen science projects like Audubonâs Christmas Bird Count also provides valuable data for researchers.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is a large bird always flightless?

- No. While many large birds like ostriches and emus are flightless, others such as the Andean condor and swan goose are strong fliers despite their size.

- What is the largest flying bird alive today?

- The wandering albatross holds the record for longest wingspanâup to 11.5 feetâthough it weighs less than 25 pounds. Among heavier flyers, the Andean condor is one of the largest, with a 10-foot wingspan and weights up to 33 pounds.

- Can you keep a large bird like an ostrich as a pet?

- In some rural areas, ostriches are raised on farms for feathers, leather, and meat. However, they are not suitable as household pets due to space requirements, specialized diets, and potential danger if startled.

- Why do large birds have long legs or necks?

- Long legs aid in running (ostrich) or wading (cranes), while long necks help reach food sources like treetop fruit (dromornithids, extinct relatives) or improve vigilance against predators.

- Are large birds intelligent?

- Yes. Studies show that birds like cassowaries and condors exhibit problem-solving skills, memory, and social learning. Though brain structure differs from mammals, avian intelligence is increasingly recognized in scientific literature.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4