A loon bird is a large, aquatic diving bird known for its haunting calls, striking black-and-white breeding plumage, and exceptional swimming and diving abilities. Often associated with remote northern lakes, the common loon (Gavia immer) is not only a symbol of wilderness and solitude but also a fascinating subject for birdwatchers and biologists alike. If you're asking 'what is a loon bird' or seeking to understand its role in nature and culture, this comprehensive guide covers everything from its biology and behavior to its symbolic significance and best practices for observing loons in their natural habitat.

Biology and Physical Characteristics of the Loon Bird

The common loon belongs to the family Gaviidae and is one of five species of loons worldwide. It is primarily found across Canada, Alaska, and the northern United States, particularly around freshwater lakes during the breeding season. In winter, loons migrate to coastal marine environments along both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

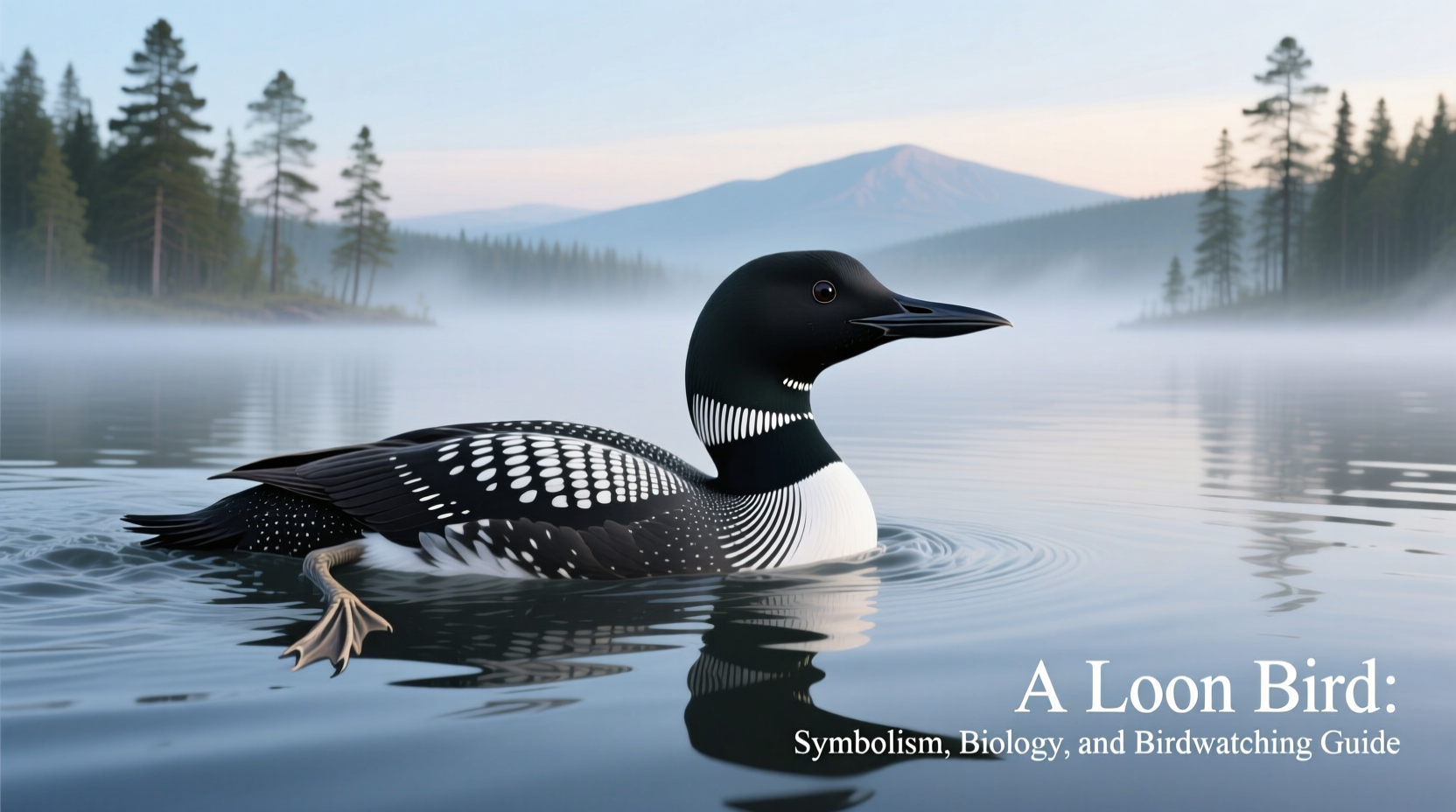

Loons are easily identified by their dagger-like bill, red eyes, and robust body built for life in water. Adults in breeding plumage display a black head, white throat patch, checkered black-and-white back, and a thick striped neck. During non-breeding seasons, they appear more subduedâgray above and white belowâwith a less distinct facial pattern.

These birds range from 61 to 91 cm (24â36 inches) in length and can weigh between 2.4 and 7 kg (5.3â15.4 lbs), making them among the heavier flying birds relative to their wingspan. Despite their weight, loons are capable of flight but require a long runway across water to take off due to their legs being positioned far back on their bodiesâa trait ideal for swimming but awkward on land.

Habitat and Distribution Patterns

Loons breed on clear, deep lakes surrounded by coniferous forests, where they build nests close to shorelines. These habitats provide access to fish, protection from predators, and minimal human disturbance. Key breeding regions include Ontario, Quebec, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Maine.

In late fall, as lakes begin to freeze, loons migrate southward. They spend winters along ocean coasts, bays, and estuaries, where food is abundant. Some individuals may travel over 1,000 miles between summer and winter ranges. Migration typically occurs at night, reducing predation risk and allowing efficient navigation using celestial cues.

Understanding where to see loon birds in North America depends on the season. Summer offers the best chance to observe nesting pairs and chicks, while winter sightings are more common offshore, especially during boat-based birdwatching tours.

Vocalizations: The Haunting Calls of the Loon

One of the most distinctive features of the loon bird is its vocal repertoire. Loons produce four primary calls: the wail, yodel, tremolo, and hootâeach serving a specific communicative function.

- The Wail: A long, mournful call resembling a wolfâs howl; used to reestablish contact between mates or family members separated on large lakes.

- The Yodel: Exclusively produced by males; a complex, rising series of notes signaling territorial defense. Each male has a unique yodel, which helps identify individual birds. \li>The Tremolo: A rapid, laughing call indicating alarm or aggression; often heard when humans approach too closely or during aerial conflicts.

- The Hoot: A short, soft call used for close-range communication within family groups, especially between parents and chicks.

These calls contribute to the loonâs reputation as a symbol of wild, untouched nature. Hearing a loon's yodel echo across a misty lake at dawn is an unforgettable experience for many outdoor enthusiasts.

Behavior and Feeding Habits

Loons are expert divers, capable of reaching depths of up to 60 meters (about 200 feet) and remaining submerged for over a minute. Their solid bones (unlike the hollow bones of most birds) reduce buoyancy, aiding deep dives. They propel themselves underwater using powerful webbed feet set far back on their bodies, steering with their wings folded tightly against their sides.

Diet consists mainly of small to medium-sized fish such as perch, minnows, and suckers, though they will also consume crustaceans, mollusks, and aquatic insects. Chicks are initially fed small prey items that adults bring to the surface.

Nesting begins in late spring, usually May or early June. Pairs form long-term bonds and often return to the same lake year after year. Nests are simple scrapes lined with vegetation, built within a few feet of water. Females typically lay one to two olive-brown, spotted eggs per clutch.

Chicks hatch after about 28 days and are able to swim within hours. They often ride on their parentsâ backs during the first two weeks, which provides warmth and protection from predators like snapping turtles, gulls, and raccoons.

Cultural and Symbolic Meaning of the Loon Bird

Beyond its biological uniqueness, the loon holds significant cultural symbolism, particularly among Indigenous peoples of North America. For many Anishinaabe communities, the loon is a sacred creature linked to creation stories. One widely shared legend tells of how the loon dove into primordial waters to retrieve mud that formed the Earthâa tale emphasizing courage, sacrifice, and connection to the spirit world.

In broader Western culture, the loon symbolizes introspection, mystery, and emotional depth. Its eerie calls evoke feelings of solitude and longing, often featured in literature and film to underscore themes of isolation or transformation. The birdâs ability to move effortlessly between air, water, and land makes it a powerful metaphor for navigating different realms of existence.

Additionally, the loon appears on the Canadian one-dollar coin, affectionately known as the âloonie,â reinforcing its national identity and ecological importance. This cultural embedding increases public awareness and supports conservation efforts.

Conservation Status and Threats Facing Loon Populations

While the common loon is currently listed as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), localized populations face growing threats. Mercury contamination, acid rain, habitat loss, and climate change all impact loon survival rates.

Methylmercury, a toxic compound formed from industrial emissions, accumulates in fish and subsequently in loons. High mercury levels impair reproduction, leading to reduced chick survival and abnormal behaviors. Studies show that even low concentrations can disrupt parental care and migration timing.

Lakefront development brings increased boat traffic, shoreline erosion, and noise pollutionâall of which disturb nesting loons. Oil spills and lead fishing tackle also pose serious risks. Ingested lead sinkers, even as small as half a gram, can cause fatal poisoning in adult loons.

Climate change alters ice melt and freeze patterns, potentially desynchronizing migration with peak food availability. Warmer temperatures may allow invasive species like smallmouth bass to invade northern lakes, preying on loon chicks.

Organizations such as the LoonWatch program at Northland College and the Biodiversity Research Institute monitor populations and advocate for clean water policies, lead-free fishing regulations, and protected nesting zones.

How to Observe Loons Responsibly: Tips for Birdwatchers

If youâre hoping to spot a loon bird in the wild, planning and ethical observation are key. Here are practical tips for maximizing your chances while minimizing disturbance:

- Visit during breeding season: Late May through July is optimal for seeing loons with chicks on inland lakes.

- Use optical aids: Bring binoculars or a spotting scope to view nests and behaviors from a distance without encroaching.

- Keep quiet and maintain distance: Stay at least 200 feet away from nesting areas. Avoid loud noises or sudden movements.

- Choose eco-friendly transportation: Canoes, kayaks, or electric-powered boats allow silent approach and reduce wake near shorelines.

- Join guided birding tours: Local Audubon chapters or wildlife refuges often offer loon-monitoring programs open to the public.

- Report sightings responsibly: Contribute data to citizen science platforms like eBird to support research and conservation tracking.

Avoid using drones near loon habitats, as they can trigger stress responses similar to predator attacks. Always follow local regulations regarding access to sensitive nesting sites.

Regional Differences in Loon Behavior and Observation Opportunities

While the basic biology of the loon remains consistent, regional variations affect viewing opportunities and conservation challenges.

| Region | Best Viewing Season | Common Challenges | Recommended Locations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota | MayâAugust | Boat traffic, shoreline development | Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness |

| Maine | JuneâJuly | Mercury pollution, tourism pressure | Rangeley Lakes, Moosehead Lake |

| Ontario | MayâSeptember | Climate variability, cottage expansion | Algonquin Provincial Park, Lake Superior |

| Washington State | Winter (NovâMar) | Oil spills, marine traffic | San Juan Islands, Puget Sound |

| Wisconsin | MayâAugust | Lead tackle use, recreational disruption | Northern Highland-American Legion State Forest |

These differences highlight why location-specific knowledge enhances both observational success and responsible stewardship.

Common Misconceptions About Loon Birds

Despite their popularity, several myths persist about loons:

- Myth: Loons can walk well on land.

Fact: Due to rear-set legs, loons struggle on land and only come ashore to nest. - Myth: Loons are ducks.

Fact: Though both are waterfowl, loons are evolutionarily distinct, more closely related to penguins than to ducks. - Myth: Loons migrate in flocks.

Fact: Most migrate alone or in small groups, unlike geese or swans. - Myth: All loon calls are sad or ominous.

Fact: Calls serve functional purposesâterritorial defense, mating, chick recognitionânot emotional expression.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What does it mean when you hear a loon call at night?

Hearing a loon call at night is common during breeding season. It usually indicates communication between mates or territorial announcements. The wail or yodel may carry farther in cool, still evening air, enhancing sound transmission across lakes.

Can loons fly?

Yes, loons can fly, though they need a long stretch of water to gain speed for takeoff. They fly strongly and directly at speeds up to 70 mph during migration.

Why do baby loons ride on their parentsâ backs?

Chicks ride on parentsâ backs for warmth, safety from predators, and rest during their first weeks of life. This behavior decreases after about three weeks as they grow stronger swimmers.

Are loon populations declining?

Overall, common loon numbers remain stable, but certain regions report declines due to mercury pollution, habitat loss, and climate impacts. Long-term monitoring shows mixed trends depending on local environmental conditions.

How can I help protect loon birds?

You can help by supporting clean water initiatives, avoiding lead fishing weights, respecting buffer zones around nests, participating in citizen science projects, and spreading awareness about loon conservation needs.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4