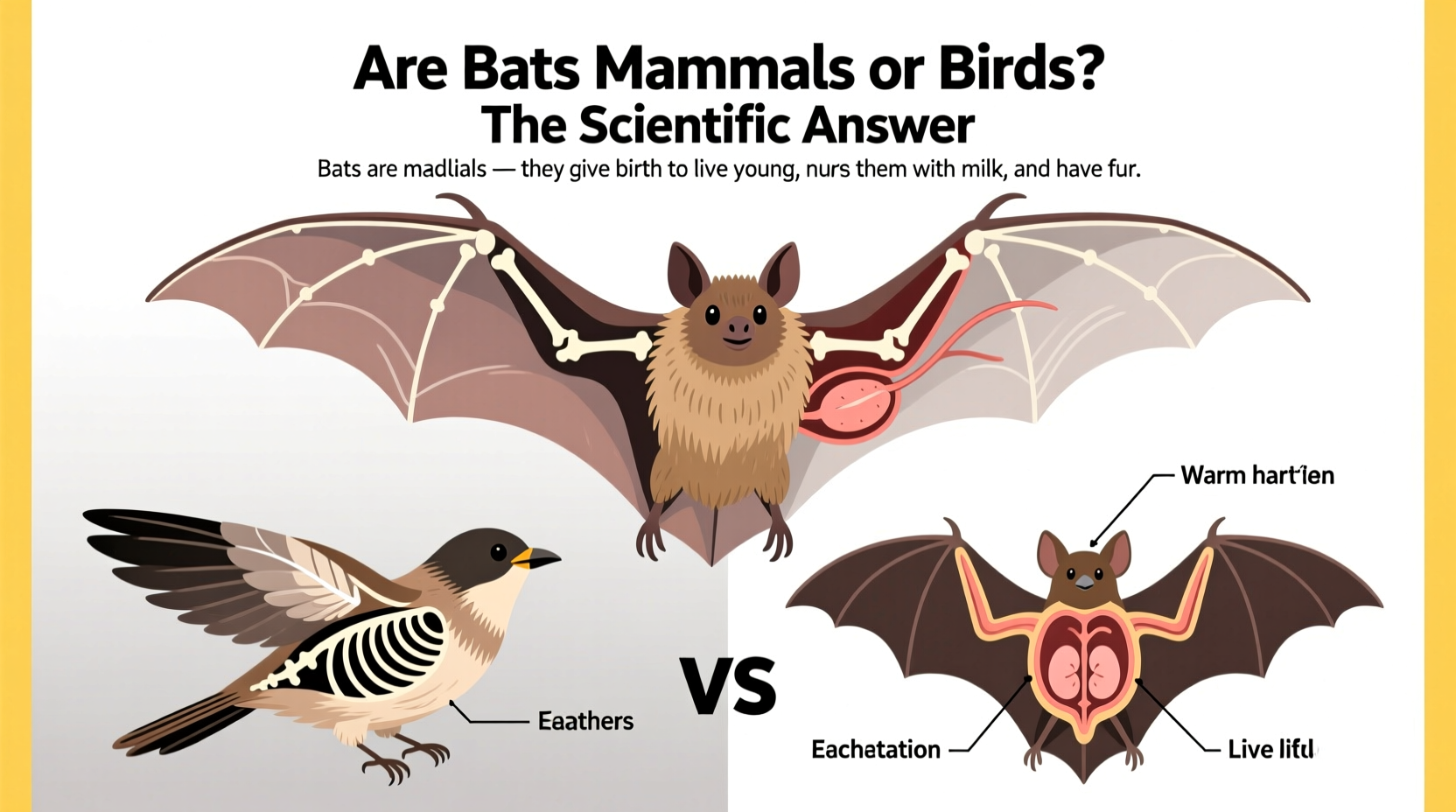

Bats are mammals, not birds—a fact confirmed by their biology, reproduction, and evolutionary lineage. Despite frequent confusion due to their ability to fly, bats belong to the class Mammalia, sharing key characteristics with humans, whales, and dogs. A common longtail keyword variant like 'are flying mammals considered birds' often arises in online searches, reflecting public uncertainty about animals that defy simple categorization. This article clarifies why bats are definitively mammals, explores the biological distinctions between bats and birds, and addresses cultural symbolism, ecological roles, and practical tips for observing both creatures in the wild.

Why Bats Are Classified as Mammals

The classification of bats within the mammalian group is based on several definitive biological traits. First and foremost, bats give birth to live young and nurse them with milk produced by mammary glands—hallmarks of all mammals. Unlike birds, which lay eggs, female bats carry their offspring internally and provide postnatal care through lactation. This reproductive strategy aligns bats more closely with house cats or dolphins than with eagles or sparrows.

Another key feature is fur. All bat species have hair at some stage of life, even if it's sparse. Hair is a defining characteristic of mammals, while birds are covered in feathers—an entirely different structure made of keratin. Feathers are unique to birds and evolved specifically for flight and insulation in avian lineages, whereas bat wings consist of thin membranes of skin stretched over elongated finger bones.

Bats also possess a neocortex in the brain, a region associated with higher-order thinking and sensory processing, which is present only in mammals. Their internal anatomy—including a four-chambered heart, diaphragm-driven respiration, and three middle ear bones (the malleus, incus, and stapes)—further confirms their placement in the mammal category.

Anatomy of Flight: How Bats Fly Without Being Birds

One reason people confuse bats with birds is their shared ability to achieve powered flight. However, the mechanics differ significantly. Bird wings are formed from forelimbs covered in feathers anchored to strong, lightweight bones adapted for aerodynamic efficiency. In contrast, bat wings are modified hands. Each wing is a double layer of skin (called the patagium) stretching from the body and legs to extremely elongated digits—especially the second through fifth fingers.

This flexible wing structure gives bats exceptional maneuverability. They can make sharp turns, hover, and even fly backward—abilities most birds cannot match. Their flight muscles attach to a prominent sternum, similar to birds, but the neuromuscular control is far more intricate, allowing micro-adjustments during flight. This dexterity supports their nocturnal hunting style, particularly when capturing insects mid-air using echolocation.

Echolocation vs. Vision: Sensory Strategies Compared

Bats rely heavily on echolocation to navigate and hunt in darkness. By emitting high-frequency sounds and interpreting the returning echoes, they build a detailed auditory map of their surroundings. While some bird species use sound for navigation (such as oilbirds and swiftlets), none employ true echolocation to the extent seen in microbats.

In contrast, birds generally depend on acute vision. Many have eyesight superior to humans, with some raptors capable of spotting prey from miles away. Diurnal birds process visual information rapidly, aiding in flight coordination and predator avoidance. Nocturnal birds like owls have large eyes optimized for low-light conditions but do not use sonar.

The reliance on echolocation further underscores the mammalian nature of bats. Among mammals, only cetaceans (dolphins and whales) share this trait, reinforcing evolutionary links within Mammalia rather than convergence with birds.

Evolutionary Origins: When Did Bats Diverge?

Fossil evidence suggests that bats diverged from other mammals around 50–60 million years ago during the early Eocene epoch. The oldest known fossil bat, Icaronycteris index, already shows adaptations for flight, indicating that powered flight evolved relatively quickly in this lineage. Unlike birds, whose ancestors were feathered dinosaurs, bats evolved from small, tree-dwelling insectivores likely resembling modern shrews or moles.

Molecular studies place bats in the clade Laurasiatheria, which includes carnivores, ungulates, and pangolins. Their closest living relatives may be found among groups like Fereuungulata, though exact phylogenetic relationships remain under study. Birds, on the other hand, are part of the reptile clade Archosauria, descending directly from theropod dinosaurs—a completely separate evolutionary path.

Table: Key Differences Between Bats and Birds

| Feature | Bats (Mammals) | Birds (Aves) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Covering | Fur/hair | Feathers |

| Reproduction | Live birth, nursing with milk | Egg-laying |

| Wing Structure | Skin membrane over elongated fingers | Feathers attached to forelimbs |

| Thermoregulation | Endothermic (warm-blooded) | Endothermic (warm-blooded) |

| Sensory Navigation | Echolocation (in most species) | Vision-dominated; limited echolocation in rare cases |

| Heart Chambers | Four | Four |

| Ear Bones | Three (malleus, incus, stapes) | One functional bone |

| Teeth | Present (varied dentition) | Absent (beak instead) |

Cultural Symbolism: Bats and Birds Across Civilizations

Despite scientific clarity, cultural perceptions often blur the lines between bats and birds. In Western traditions, bats are sometimes mythologized as 'flying mice' or associated with darkness and superstition. Conversely, many bird species symbolize freedom, peace, or divine messages—e.g., doves representing hope or ravens embodying prophecy.

In Chinese culture, the bat is a symbol of good fortune and longevity—the word for bat (fu) sounds like the word for 'good luck.' Bat imagery appears in art and architecture, often stylized similarly to birds. This artistic blending contributes to public confusion, especially when illustrations depict bats with feather-like wings.

Indigenous Mesoamerican cultures revered bats as underworld messengers, while certain African folklore portrays them as mediators between humans and spirits. Meanwhile, birds such as eagles, hawks, and owls frequently serve as national symbols or spiritual totems across diverse societies.

Ecological Roles: Why Both Matter

Bats play vital roles in ecosystems worldwide. Over 70% of bat species are insectivorous, consuming vast quantities of mosquitoes, moths, and agricultural pests nightly. A single little brown bat can eat up to 1,000 insects per hour, making them crucial natural pest controllers.

Fruit-eating bats (like those in the family Pteropodidae) are essential pollinators and seed dispersers in tropical regions. They help regenerate forests and sustain biodiversity by transporting seeds across fragmented landscapes. Some plants, including agave (used for tequila) and banana relatives, depend entirely on bats for pollination.

Birds also contribute significantly to ecosystem balance. Seed-dispersing birds like toucans and hornbills maintain forest health, while raptors regulate rodent populations. Nectar-feeding birds such as hummingbirds support plant reproduction much like bees. Understanding these complementary roles enhances conservation efforts for both groups.

Observing Bats and Birds: Practical Tips for Enthusiasts

For wildlife watchers, distinguishing bats from birds in flight requires attention to timing and movement patterns. Bats typically emerge shortly after sunset, flying erratically as they hunt insects. Their flight is fluttery and unpredictable, unlike the smoother, directional flight of most birds.

To observe bats:

- Visit parks, lakes, or rivers at dusk.

- Look near streetlights where insects gather.

- Use a bat detector to hear ultrasonic calls converted into audible range.

- Avoid disturbing roosts in caves, attics, or bridges—many species are protected.

For birdwatching:

- Carry binoculars and a field guide suited to your region.

- Visit early in the morning when birds are most active.

- Listen for songs and calls—many species are identified by sound before sight.

- Join local birding groups or use apps like eBird to log sightings.

Common Misconceptions About Bats

Several myths persist about bats, contributing to fear and misunderstanding:

- Misconception: Bats are blind.

Fact: Bats can see, though many rely more on echolocation in dark environments. - Misconception: All bats carry rabies.

Fact: Less than 1% of bats contract rabies; transmission to humans is extremely rare. - Misconception: Bats get tangled in human hair.

Fact: This is virtually impossible; their echolocation prevents collisions with obstacles. - Misconception: Bats are rodents.

Fact: Bats are not related to rodents; genetically, they’re closer to primates and carnivores.

Conservation Status and Threats

Both bats and birds face growing threats from habitat loss, climate change, and human activity. White-nose syndrome, a fungal disease, has killed millions of North American bats since 2006. Wind turbines also pose a significant risk, with thousands of bats dying annually from barotrauma near blades.

Birds confront dangers from window collisions, domestic cats, and pesticide use. Migratory species are especially vulnerable to disruptions in food availability and stopover sites. Protecting natural habitats, reducing light pollution, and supporting wildlife-friendly policies benefit both animal groups.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are bats the only mammals that can fly?

- Yes, bats are the only mammals capable of sustained, powered flight. Other gliding mammals (like flying squirrels or colugos) can parachute short distances but cannot achieve true flight.

- Do any birds give live birth?

- No. All birds reproduce by laying hard-shelled eggs. Live birth is exclusive to certain mammals, reptiles, and fish—but never in avian species.

- Can bats swim?

- While not adapted for swimming, some bats can paddle briefly if they fall into water. Most avoid it unless necessary.

- Why do people think bats are birds?

- Because both fly, the assumption arises from superficial similarity. Historical classifications before modern taxonomy sometimes grouped flying animals together regardless of biology.

- How many species of bats exist?

- There are over 1,400 known bat species, making them the second-largest order of mammals after rodents.

In conclusion, the question 'are bats mammals or birds' has a clear scientific answer: bats are mammals. Their physiology, reproduction, and genetics firmly place them in the class Mammalia. While they share the skies with birds, their evolutionary journey, anatomical design, and ecological functions set them apart. Appreciating these differences enriches our understanding of biodiversity and highlights the importance of accurate biological knowledge in conservation and education.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4