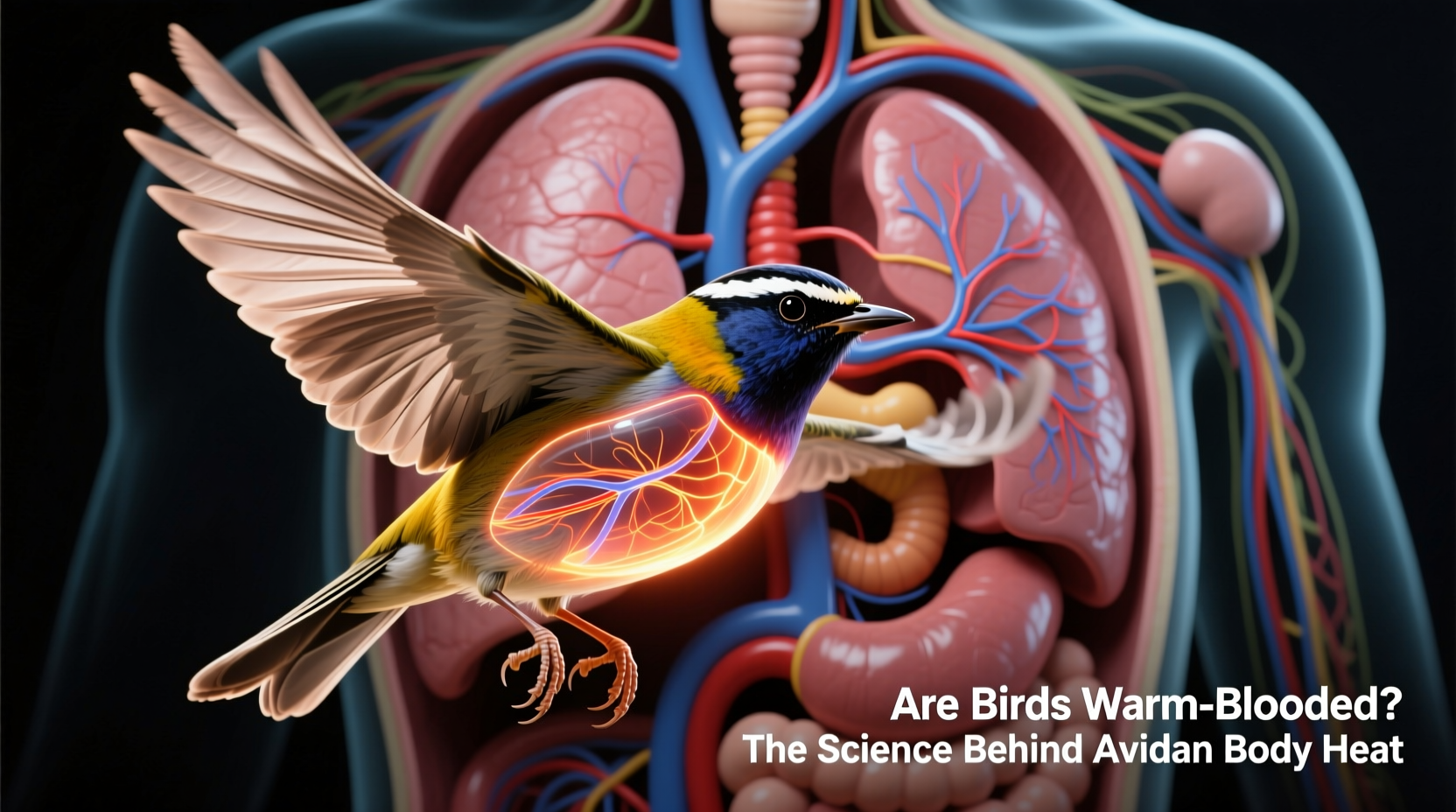

Yes, birds are warm-blooded, meaning they maintain a stable internal body temperature regardless of external environmental conditions. This biological trait, also known as endothermy, allows birds to remain active in cold climates and at high altitudes where temperatures fluctuate dramatically. A natural longtail keyword variant like "how do birds stay warm-blooded in winter" reflects the curiosity behind this physiological marvel—how do these often small-bodied creatures generate and conserve enough heat to survive? Unlike cold-blooded (ectothermic) animals such as reptiles, which rely on external heat sources to regulate their metabolism, birds produce metabolic heat internally through rapid cellular processes, especially in organs like the liver and flight muscles.

The Biology of Being Warm-Blooded in Birds

Birds, like mammals, are classified as endotherms—organisms that generate their own body heat. Most bird species maintain a core body temperature between 104°F and 108°F (40°C to 42.2°C), significantly higher than the average human body temperature of 98.6°F (37°C). This elevated temperature supports faster metabolic rates, essential for energy-intensive activities such as sustained flight, rapid digestion, and quick neural responses.

The primary source of heat production in birds is through metabolic activity, particularly in the pectoral muscles used during flight. When birds flap their wings, muscle contractions not only propel them through the air but also release substantial thermal energy. Even at rest, birds have a high basal metabolic rate compared to ectothermic animals. For example, a resting pigeon consumes oxygen at a rate comparable to a similarly sized mammal engaged in moderate exercise.

To sustain this level of energy output, birds require frequent feeding. Many small songbirds eat up to 25% of their body weight daily. Their digestive systems are highly efficient, processing food quickly to fuel continuous heat generation. This necessity explains why you might observe birds visiting feeders repeatedly throughout the day, especially in colder months when energy demands increase.

Evolutionary Origins of Endothermy in Birds

The warm-blooded nature of birds has deep evolutionary roots. Birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs, a group that includes well-known genera like Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus rex. Fossil evidence and phylogenetic studies suggest that some dinosaur lineages may have already possessed elevated metabolic rates, possibly indicating early forms of endothermy.

Feathers, one of the defining characteristics of birds, likely first evolved not for flight but for insulation. Early feathered dinosaurs such as Sinosauropteryx had filamentous structures covering their bodies, which would have helped retain body heat. Over millions of years, as avian ancestors adapted to more dynamic lifestyles—including powered flight—maintaining a constant internal temperature became increasingly advantageous.

This evolutionary shift allowed birds to colonize diverse habitats, from Arctic tundras to tropical rainforests. The ability to remain thermally independent from ambient temperatures gave them an edge over ectothermic competitors, enabling greater mobility, longer activity periods, and expanded geographic ranges.

How Birds Regulate Body Temperature

Maintaining a consistent internal temperature requires sophisticated physiological and behavioral adaptations. Birds employ several mechanisms to balance heat production and loss:

- Insulation via Feathers: Contour feathers form a streamlined outer layer, while down feathers trap pockets of air close to the skin, creating an effective insulating barrier. Fluffing their feathers increases trapped air volume, enhancing warmth retention.

- Vasomotor Control: Birds can constrict blood vessels in their extremities (like legs and feet) to reduce heat loss. In cold environments, they minimize blood flow to unfeathered areas, preventing excessive cooling without risking tissue damage.

- Shivering Thermogenesis: Like humans, birds shiver to generate heat. Rapid muscle contractions produce warmth during periods of cold stress.

- Countercurrent Heat Exchange: In the legs of waterfowl and wading birds, arteries and veins are arranged so that warm arterial blood transfers heat to cooler venous blood returning from the feet. This system conserves core body heat while allowing limbs to function in icy water.

- Behavioral Adjustments: Roosting in sheltered locations, huddling together, sunbathing, and adopting compact postures reduce surface area exposure and improve thermal efficiency.

Why Being Warm-Blooded Matters for Migration and Survival

Bird migration is one of the most impressive feats in the animal kingdom, with species like the Arctic Tern traveling over 40,000 miles annually between polar regions. Sustained flight across vast distances and extreme climates would be impossible without endothermy.

During long migratory flights, birds rely on fat stores as fuel. These reserves are metabolized efficiently to produce both mechanical energy and heat. High-altitude migrants, such as bar-headed geese flying over the Himalayas, face low oxygen levels and subzero temperatures. Their warm-blooded physiology enables them to maintain aerobic performance under hypoxic conditions, thanks to specialized hemoglobin and enhanced lung capacity.

In winter, non-migratory birds depend heavily on thermoregulatory strategies. Chickadees, for instance, enter a state of regulated hypothermia called torpor at night, lowering their body temperature by several degrees to reduce energy expenditure. However, they still maintain sufficient warmth to remain alert and responsive—a fine-tuned adaptation within the broader framework of endothermy.

Comparative Physiology: Birds vs. Mammals vs. Reptiles

Understanding whether birds are warm-blooded becomes clearer when comparing them to other vertebrate classes. The table below highlights key differences:

| Feature | Birds | Mammals | Reptiles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Temperature Regulation | Endothermic (warm-blooded) | Endothermic (warm-blooded) | Ectothermic (cold-blooded) |

| Average Body Temperature | 104–108°F (40–42.2°C) | 97–100°F (36–38°C) | Varies with environment |

| Primary Insulation | Feathers | Fur/Hair | Scales |

| Metabolic Rate | Very high | High | Low to moderate |

| Energy Requirements | High (frequent feeding) | Moderate to high | Low (can fast for days/weeks) |

| Activity in Cold Weather | Active year-round | Mostly active | Limited; sluggish when cold |

While both birds and mammals are warm-blooded, birds generally exhibit higher metabolic rates and body temperatures. However, they lack sweat glands and cannot cool themselves through perspiration. Instead, they dissipate excess heat through panting, gular fluttering (rapid vibration of throat membranes), and exposing unfeathered skin on legs or around the eyes.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Thermoregulation

Despite scientific consensus, several myths persist about bird biology. One common misconception is that birds’ feet freeze to metal perches—an urban legend with no basis in fact. Birds’ scaly legs have minimal blood flow in cold weather, and their tissues are resistant to freezing. Moreover, metal conducts heat away slowly unless extremely cold, making actual freezing unlikely.

Another myth suggests that feeding birds in summer disrupts their natural instincts. In reality, supplemental feeding has little impact on healthy populations' thermoregulatory behaviors. However, providing appropriate foods (e.g., suet in winter, nectar for hummingbirds) can support energy needs during temperature extremes.

Practical Tips for Observing Warm-Blooded Behavior in Birds

For birdwatchers interested in witnessing thermoregulatory behaviors firsthand, here are actionable tips:

- Observe Fluffing Behavior: On cold mornings, look for birds appearing “puffed up.” This fluffing indicates active insulation adjustment.

- Watch for Huddling: Species like chickadees or sparrows often roost together in dense foliage or cavities. This communal behavior reduces individual heat loss.

- Note Sunbathing Postures: On chilly but sunny days, birds may spread wings or tilt bodies toward sunlight to absorb radiant heat.

- Identify Panting in Heat: During hot weather, pigeons, crows, and raptors may be seen breathing rapidly with open mouths—signs of evaporative cooling.

- Use Thermal Imaging (if available): Some wildlife researchers use infrared cameras to visualize heat distribution in perched or flying birds, revealing how different body parts retain or lose warmth.

Climate Change and Its Impact on Avian Endothermy

As global temperatures rise, the advantages of being warm-blooded face new challenges. While birds can tolerate cold better than heat due to their high baseline temperatures, extreme heatwaves pose serious risks. Prolonged exposure to temperatures above 104°F can lead to hyperthermia, dehydration, and even death—especially in nestlings or sedentary individuals.

Urban heat islands exacerbate this issue. City-dwelling birds may struggle to find shaded microhabitats or adequate water sources. Conservation efforts now focus on creating green corridors, installing bird baths, and preserving mature trees that offer shade and roosting sites.

Conversely, climate shifts may allow certain species to expand northward without needing full migration. However, mismatches in timing—such as earlier insect emergence versus delayed nesting—can strain energy budgets, testing the limits of endothermic resilience.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are all birds warm-blooded?

- Yes, all modern bird species are warm-blooded. There are no known exceptions among living avian taxa.

- Can birds get hypothermia?

- Yes, if exposed to prolonged cold without sufficient food or shelter, birds can suffer from hypothermia. However, their physiological defenses make this rare under normal conditions.

- Do baby birds regulate their own temperature?

- Nestlings are initially poikilothermic (relying on external warmth) and depend on parental brooding. As they grow feathers and develop muscles, they gradually become fully endothermic.

- How do penguins stay warm in Antarctica?

- Penguins combine thick blubber layers, tightly packed waterproof feathers, huddling behavior, and countercurrent circulation to survive extreme cold.

- Is being warm-blooded more energy-efficient?

- No—endothermy is energetically expensive. Birds must eat frequently to sustain it. However, the trade-off is increased mobility, endurance, and adaptability across environments.

In conclusion, the answer to "are birds warm-blooded" is definitively yes. Their endothermic physiology is a cornerstone of avian success, enabling flight, global distribution, and survival in some of Earth’s harshest climates. From tiny hummingbirds to soaring albatrosses, warm-bloodedness defines what it means to be a bird in both biological and ecological terms. Understanding this trait enhances our appreciation of avian life and informs conservation practices in a changing world.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4