Birds are not warm-blooded reptiles; rather, birds are warm-blooded vertebrates that evolved from reptilian ancestors. While this may sound contradictory at first, the question are birds warm-blooded reptiles touches on a fascinating intersection of evolutionary biology, taxonomy, and physiology. In short: birds are warm-blooded (endothermic), like mammals, but they share a direct evolutionary lineage with reptiles—specifically theropod dinosaurs. This makes them biologically distinct from modern reptiles, despite common ancestry. Understanding whether birds are warm-blooded reptiles requires unpacking both scientific classification and the nuances of how traits like metabolism, skeletal structure, and reproduction define animal groups.

The Evolutionary Link Between Birds and Reptiles

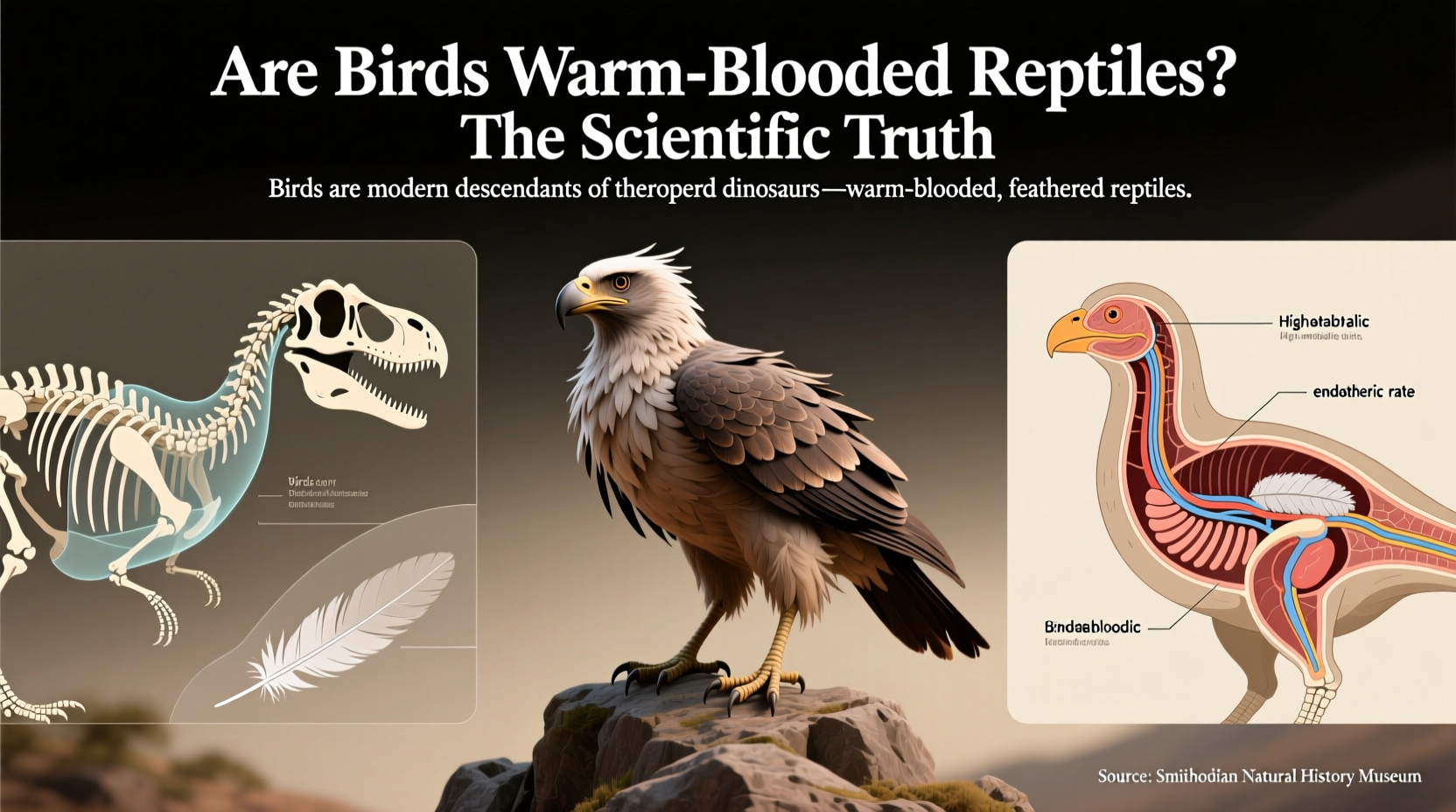

One of the most compelling arguments for considering birds as descendants of reptiles lies in paleontological evidence. Fossil discoveries over the past 150 years have consistently shown that birds evolved from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, approximately 150 million years ago. The famous Archaeopteryx lithographica, discovered in Germany in 1861, exhibits both reptilian features (teeth, long bony tail) and avian traits (feathers, wings), serving as a key transitional fossil.

Modern phylogenetic classification, based on cladistics, places birds within the clade Archosauria, which also includes crocodilians and extinct dinosaurs. Under this system, birds are considered a subgroup of reptiles in the broadest evolutionary sense—but not in traditional Linnaean taxonomy. This distinction is crucial when answering questions like are birds warm-blooded reptiles. While birds share ancestry with reptiles, they have evolved significant physiological differences, especially regarding thermoregulation.

What Does 'Warm-Blooded' Mean?

Warm-bloodedness, or endothermy, refers to an organism’s ability to maintain a stable internal body temperature regardless of external conditions. This is achieved through metabolic processes that generate heat internally. Mammals and birds are the only two animal groups that are fully endothermic.

In contrast, most reptiles are ectothermic, meaning they rely on external sources of heat—such as sunlight or warm surfaces—to regulate their body temperature. This fundamental difference in metabolism separates birds from the majority of living reptiles. When exploring whether birds are warm-blooded reptiles, it's important to recognize that being warm-blooded is not a trait typically associated with reptiles, making the phrase itself somewhat misleading.

However, recent research suggests that some ancient reptiles—and possibly certain dinosaurs—may have had elevated metabolic rates, blurring the line between ectothermy and endothermy. Some scientists propose a spectrum of thermoregulatory strategies rather than a strict dichotomy. Still, by modern standards, birds stand out among sauropsids (the larger group including reptiles and birds) as the only consistently warm-blooded members.

Biological Differences Between Birds and Reptiles

Despite their shared ancestry, birds and reptiles differ significantly in anatomy, physiology, and life history. Below is a comparative overview:

| Feature | Birds | Reptiles |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolism | Endothermic (warm-blooded) | Ectothermic (cold-blooded) |

| Body Covering | Feathers | Scales |

| Respiration | Highly efficient lungs with air sacs | Lungs without air sacs |

| Heart Structure | Four-chambered heart | Three-chambered (most), four in crocodilians |

| Reproduction | Egg-laying with hard shells, often incubated | Egg-laying (mostly), some live-bearing |

| Development | Altricial or precocial hatchlings | Precocial young, independent at birth |

| Skeleton | Lightweight, fused bones, keeled sternum | Heavier, less specialized for flight |

This table highlights why, although birds evolved from reptiles, they are functionally and physiologically distinct. For example, feathers—unique to birds among living animals—are critical for flight and insulation, supporting high metabolic rates. Their respiratory system allows for continuous airflow and greater oxygen uptake, essential for sustained flight. These adaptations support the conclusion that while birds may be descended from reptiles, they are not reptiles in the conventional biological sense.

Taxonomic Classification: Where Do Birds Fit?

Traditional taxonomy, developed by Carl Linnaeus, classified animals into six main classes: Mammalia, Aves, Reptilia, Amphibia, Pisces, and Insecta. Under this system, birds (class Aves) and reptiles (class Reptilia) are separate classes, emphasizing morphological differences.

Modern systematics, however, uses cladistics—classification based on common ancestry. From this perspective, since birds evolved from dinosaurs, and dinosaurs are reptiles, birds can be considered a type of reptile. Some biologists refer to birds as “avian reptiles” to reflect this relationship. However, this usage is primarily academic and does not imply that birds are cold-blooded or otherwise similar to lizards, snakes, or turtles.

So, when someone asks are birds warm-blooded reptiles, the answer depends on context. Biologically and functionally, birds are not reptiles as commonly understood. But evolutionarily, they are part of the reptile lineage. This duality reflects how science updates its understanding over time, integrating new data from genetics, fossils, and developmental biology.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds vs. Reptiles

Beyond biology, birds hold vastly different cultural symbolism compared to reptiles. Across civilizations, birds are often associated with freedom, spirituality, and transcendence—think of doves representing peace or eagles symbolizing national strength. Many mythologies feature bird-like deities or messengers between realms (e.g., Garuda in Hinduism, Horus in Egyptian mythology).

In contrast, reptiles—especially snakes and crocodiles—are frequently depicted as dangerous, cunning, or primordial forces. The serpent in the Garden of Eden, the dragon in medieval legends, or the nagas in Asian folklore all reflect ambivalence toward reptiles, often linking them to chaos or hidden knowledge.

This symbolic divide reinforces the public perception that birds and reptiles are fundamentally different kinds of animals, even if science reveals a closer kinship. It also influences how people interpret questions like are birds warm-blooded reptiles—many instinctively resist the idea due to cultural associations.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers and Nature Enthusiasts

For birdwatchers, understanding avian biology enhances the experience. Knowing that birds are warm-blooded explains why they remain active in cold weather, fluffing feathers for insulation or shivering to generate heat. Observing behaviors such as sunbathing or seeking sheltered perches can reveal how birds manage energy and temperature.

Additionally, recognizing the dinosaur heritage of birds adds depth to field observations. Watching a crow use tools or a raptor soar on thermal currents connects modern behavior to deep evolutionary roots. Some bird species, like the cassowary or roadrunner, retain more reptilian postures and movements, offering glimpses into ancestral forms.

If you're planning a birdwatching trip, consider visiting regions with high avian diversity and ancient lineages, such as Australia (home to primitive birds like the emu) or New Zealand (with the kiwi and extinct moa). Museums with paleontology exhibits—like the American Museum of Natural History or the Royal Tyrrell Museum—also provide excellent opportunities to see fossils linking birds and dinosaurs.

Common Misconceptions About Birds and Reptiles

Several myths persist about the relationship between birds and reptiles:

- Misconception: Birds are just flying reptiles.

Reality: While birds evolved from reptiles, they have undergone extensive adaptation, especially in respiration, locomotion, and metabolism. - Misconception: All reptiles are cold-blooded, so birds can't be related.

Reality: Evolution allows for new traits to emerge. Endothermy evolved independently in birds and mammals. - Misconception: If birds are reptiles, then chickens are lizards.

Reality: Shared ancestry doesn’t mean identical classification. Humans and fish share a common ancestor, but we aren’t fish.

Clarifying these points helps prevent confusion when encountering scientific statements like “birds are reptiles.” Precision in language matters, especially when communicating complex biological ideas to the public.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Are birds warm-blooded?

A: Yes, birds are warm-blooded (endothermic), maintaining a constant internal body temperature through metabolic activity.

Q: Did birds evolve from reptiles?

A: Yes, birds evolved from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs, which are part of the reptile lineage.

Q: Can birds be classified as reptiles?

A: In traditional taxonomy, no—birds are in class Aves. In modern cladistics, birds are considered avian reptiles due to shared ancestry.

Q: Why aren’t birds considered cold-blooded like other reptiles?

A: Birds evolved endothermy, likely as an adaptation for flight and activity in varied climates, distinguishing them from ectothermic reptiles.

Q: Do any reptiles have warm-blooded traits?

A: Some large reptiles, like leatherback sea turtles and certain monitor lizards, show limited regional endothermy, but none are fully warm-blooded like birds.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4