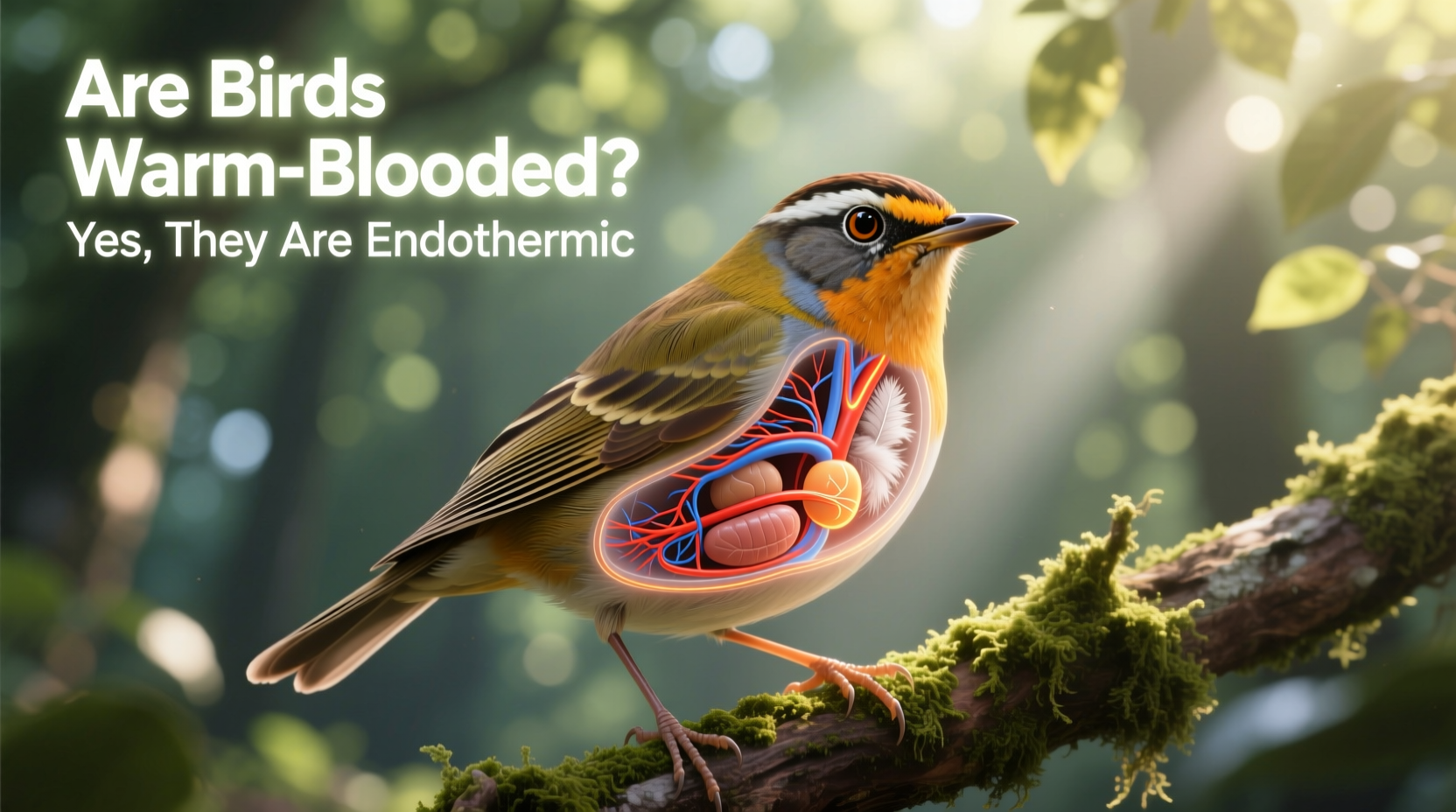

Yes, birds are warm-blooded, meaning they maintain a stable internal body temperature regardless of their environmentâa trait known as endothermy. This biological adaptation allows them to stay active in cold climates, fly at high altitudes, and sustain the high metabolic rates necessary for flight. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'are birds warm or cold blooded and how does that affect their survival' reflects a common search intent: understanding not just the classification but also the functional significance behind it. Unlike cold-blooded animals whose body temperatures fluctuate with ambient conditions, birds generate heat internally through metabolic processes, keeping their core temperatures typically between 104°F and 110°F (40°Câ43°C).

The Science Behind Avian Endothermy

Birds belong to a group of animals called endotherms, which include mammals and birds. Endothermy refers to the ability to produce internal heat to regulate body temperature. This is in contrast to ectothermyâseen in reptiles, amphibians, and most fishâwhere body temperature depends on external sources like sunlight or water.

In birds, endothermy evolved alongside other adaptations crucial for powered flight. High-energy activities like flapping flight require consistent muscle performance, which only a stable internal temperature can support. To fuel this system, birds have extremely efficient respiratory and circulatory systems. Their four-chambered hearts completely separate oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, maximizing oxygen delivery to tissuesâcritical for sustaining high metabolism.

Metabolically, birds burn energy at rates far exceeding those of similarly sized mammals. For example, a small songbird may consume several times its body weight in food each day during winter months simply to maintain thermal balance. This high metabolic rate generates substantial heat as a byproduct, which birds actively manage using insulation (feathers), behavioral strategies (shivering, postural changes), and physiological mechanisms (vasoconstriction/vasodilation).

Evolutionary Origins of Warm-Bloodedness in Birds

The evolutionary roots of bird endothermy trace back to their dinosaur ancestors. Paleontological evidence suggests that some theropod dinosaursâthe lineage leading to modern birdsâmay have exhibited early signs of warm-blooded physiology. Fossilized bones with Haversian canals (indicative of fast growth and high metabolic activity), along with discoveries of feathered dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Archaeopteryx, point toward a gradual transition from ectothermic reptilian ancestors to fully endothermic modern birds.

Feathers, originally likely used for insulation or display, became central to thermoregulation. Over millions of years, natural selection favored individuals capable of maintaining body heat, especially as ecological niches expanded into colder environments. The development of insulative down feathers, combined with increased aerobic capacity, allowed proto-birds to remain active during cooler periods when predators and competitors were less agile.

This shift had profound implications: it enabled nocturnal activity, migration across climate zones, and colonization of diverse habitatsâfrom Arctic tundras to alpine peaks. Today, species like the Common Eider survive in sub-zero temperatures thanks to dense plumage and counter-current heat exchange in their legs, minimizing heat loss while swimming in icy waters.

How Birds Regulate Body Temperature

Maintaining a constant body temperature requires sophisticated control systems. Birds use a combination of anatomical, physiological, and behavioral strategies to prevent overheating or excessive cooling:

- Insulation: Feathers provide exceptional thermal insulation. Down feathers trap air close to the skin, creating a buffer against cold. Preening helps maintain feather alignment and waterproofing, preserving insulative properties.

- Shivering Thermogenesis: Like mammals, birds can generate heat through involuntary muscle contractions (shivering), especially during cold exposure. \li>Non-Shivering Thermogenesis: Some birds, particularly young chicks and small species, produce heat in specialized fat tissue (brown adipose tissue), though this mechanism is more limited than in mammals.

- Vasomotor Control: By constricting blood vessels in extremities (like legs and feet), birds reduce heat loss. In aquatic birds, a countercurrent heat exchange system transfers warmth from outgoing arterial blood to returning venous blood, conserving core heat.

- Behavioral Adaptations: Roosting in sheltered locations, tucking beaks into feathers, huddling in groups, and sunbathing all help conserve or absorb heat.

Conversely, in hot environments, birds dissipate excess heat through panting, gular fluttering (rapid vibration of throat membranes), and spreading wings to increase airflow. They lack sweat glands, so evaporative cooling via respiration is their primary method of heat release.

Biological Advantages and Trade-Offs of Being Warm-Blooded

Endothermy offers significant advantages but comes with energetic costs. Key benefits include:

| Advantage | Description |

|---|---|

| Environmental Independence | Birds can remain active in cold weather when ectothermic animals are sluggish or dormant. |

| Sustained Activity | Flight, hunting, and migration demand continuous energy output supported by stable internal temperatures.|

| Niche Expansion | Enables survival in extreme environmentsâfrom deserts to polar regions.|

| Faster Neural Processing | Warm brains operate more efficiently, enhancing sensory perception and coordination.

However, these benefits come at a price. Birds must eat frequentlyâsometimes every few hoursâto meet caloric demands. During winter nights, small birds like chickadees can lose up to 10% of their body mass overnight just maintaining heat. Starvation risk is high if food is unavailable for even a short period.

This delicate balance makes habitat quality and food availability critical for survival. Conservation efforts often focus on preserving feeding grounds and sheltered roost sites, especially during migration and winter seasons.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birdsâ Warm-Blooded Nature

While scientific understanding of avian endothermy is relatively recent, human cultures have long associated birds with vitality, spirit, and transcendenceâqualities metaphorically linked to warmth and life force. In many traditions, birds symbolize the soul or divine messengers, perhaps due to their ability to soar above the earth into the heavens, a movement suggestive of spiritual ascension.

Their constant motion and apparent tirelessnessâenabled by warm-blooded enduranceâreinforce images of freedom and resilience. For instance, eagles represent power and vision in Native American symbolism, while doves embody peace and purity in Judeo-Christian traditions. These symbolic meanings gain deeper resonance when viewed through the lens of biology: their internal fire allows them to rise above terrestrial limits, both literally and figuratively.

In literature and art, the image of a bird enduring harsh winters or flying vast distances mirrors human aspirations for perseverance and transformation. Understanding that this endurance stems from physiological warmth adds a layer of biological truth to these metaphors.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers and Conservationists

Knowing that birds are warm-blooded enhances observational skills and informs ethical wildlife practices. Here are actionable tips for bird enthusiasts:

- Winter Feeding: Provide high-energy foods like black oil sunflower seeds, suet, and peanuts to help birds meet increased metabolic demands in cold weather.

- Water Access: Offer unfrozen drinking water using heated birdbaths. Dehydration is a hidden threat in winter, as snow alone doesnât suffice for hydration.

- Shelter: Plant native shrubs and trees or install roost boxes to give birds protection from wind and predators.

- Avoid Disturbance: Minimize approaching nests or roosting birds closely, especially in cold weather, to prevent unnecessary energy expenditure.

- Monitor Behavior: Look for signs of thermoregulatory stressâsuch as prolonged shivering, lethargy, or open-mouth breathing in heatâas potential indicators of distress.

For researchers, studying thermoregulation helps assess speciesâ vulnerability to climate change. As global temperatures shift, some birds may struggle to cope with increased heat loads, especially in urban areas where heat retention is high. Monitoring microhabitat use and behavioral adjustments provides insight into adaptive capacity.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Physiology

Despite widespread knowledge, misconceptions persist. One common error is assuming that because birds are related to reptiles, they must be cold-blooded. While birds evolved from reptilian ancestors, they developed endothermy independently or inherited early stages of it. Another myth is that all small animals are cold-bloodedâbut hummingbirds, weighing less than a nickel, maintain body temperatures near 107°F (42°C).

Some people believe birds freeze easily in winter, failing to recognize their complex adaptations. Others assume panting always indicates illness, when in fact itâs a normal cooling behavior in warm conditions.

FAQs About Bird Thermoregulation

- Do all birds have the same body temperature?

- No, while most birds range between 104°F and 110°F (40â43°C), there is variation by species, size, and activity level. Smaller birds often have higher metabolic rates and slightly elevated temperatures.

- Can birds get hypothermia?

- Yes. If energy reserves are depleted and environmental temperatures are too low, birds can suffer hypothermia. Young, sick, or injured birds are most at risk.

- Why donât birds freeze their feet in snow?

- Birds minimize heat loss through their legs via a countercurrent heat exchange system. Blood flowing to the feet is cooled before reaching extremities, reducing thermal loss while preventing tissue damage.

- How do desert birds stay cool?

- Desert species like roadrunners use gular fluttering, seek shade, become less active during peak heat, and may aestivate (a state of dormancy) during extreme conditions.

- Is being warm-blooded unique to birds and mammals?

- Mostly yes. However, some fish like tuna and certain sharks exhibit regional endothermy, warming specific muscles or eyes for enhanced performance, though they are not fully warm-blooded like birds.

In conclusion, birds are definitively warm-blooded, a defining characteristic that underpins their remarkable abilities to fly, migrate, and thrive in varied ecosystems. This internal regulation of temperature is not merely a biological detailâit shapes their behavior, ecology, and symbolic presence in human culture. Whether you're a casual observer or dedicated ornithologist, recognizing the role of endothermy deepens appreciation for the dynamic lives of birds.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4