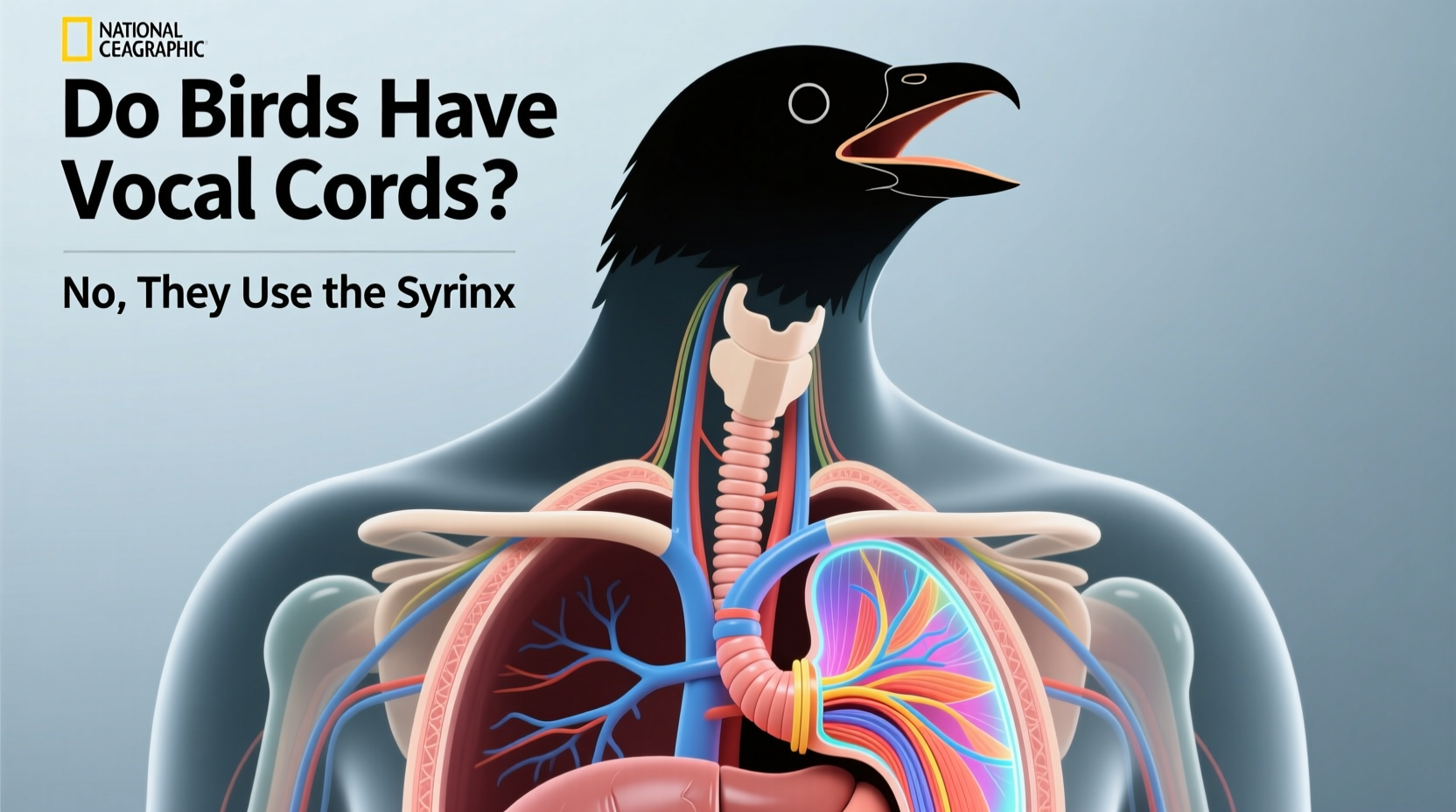

Birds do not have vocal cords like mammals; instead, they produce their wide range of calls and songs using a specialized organ called the syrinx, located at the junction where the trachea splits into the bronchi. This fundamental difference in avian anatomy explains how birds can produce such complex and varied sounds despite lacking the larynx-based vocal cords found in humans and other mammals. A common long-tail keyword variant related to this topic is "how do birds make sounds without vocal cords," which reflects widespread curiosity about avian communication mechanisms.

The Science Behind Bird Vocalization: The Role of the Syrinx

The syrinx is a uniquely avian structure that serves as the primary sound-producing organ in most bird species. Unlike the mammalian larynx, which houses vocal cords that vibrate as air passes through, the syrinx operates at the lower end of the respiratory tract. When air flows from the lungs through the bronchial tubes, it causes soft tissues within the syrinx to vibrate, generating sound. These vibrations are then modulated by muscles surrounding the syrinx, allowing precise control over pitch, volume, and tone.

One of the most remarkable features of the syrinx is its bilateral symmetry. In many songbirds (oscines), each side of the syrinx can operate independently, enabling them to produce two different sounds simultaneously—a phenomenon known as dual-voice production. This capability allows certain species, such as the northern cardinal or European starling, to create richly layered songs that would be impossible with a single sound source.

Research has shown that the complexity of syrinx anatomy correlates with the sophistication of vocal behavior. For example, parrots, hummingbirds, and songbirds—groups renowned for their vocal learning abilities—possess highly developed syringeal musculature. In contrast, non-vocal learners like pigeons and chickens have simpler syrinx structures and produce more limited repertoires of calls.

Evolutionary Advantages of the Syrinx Over Vocal Cords

The evolution of the syrinx represents a significant adaptation in avian biology. Because it is positioned deeper in the respiratory system than the larynx, birds can generate sound more efficiently while maintaining unobstructed airflow—critical for animals that require high oxygen intake during flight. Additionally, the location of the syrinx reduces the risk of choking, as it doesn’t interfere with the passage of food through the esophagus, which runs parallel to the trachea.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the syrinx likely emerged as a solution to the biomechanical constraints faced by early birds. Fossil evidence suggests that the transition from dinosaur-like ancestors to modern birds involved reorganization of the respiratory and vocal systems. While some theropod dinosaurs may have used air sacs or simple laryngeal structures for communication, the development of the syrinx allowed for greater acoustic diversity, aiding in mate attraction, territory defense, and social cohesion.

Interestingly, no fossilized syrinx has been definitively identified until relatively recently. In 2016, researchers discovered a mineralized syrinx in a Late Cretaceous specimen of Vegavis iaai, an ancient relative of ducks and geese. This finding provided the first direct evidence that some prehistoric birds possessed the anatomical machinery for complex vocalizations, pushing back the origins of avian song to at least 66 million years ago.

How Bird Species Differ in Sound Production

Not all birds use the syrinx in the same way. There are notable differences across taxonomic groups in terms of syrinx structure, neural control, and vocal output. These variations reflect both ecological niches and behavioral needs.

Oscine passerines (true songbirds), such as robins, warblers, and finches, have the most advanced syrinx and exhibit sophisticated vocal learning. Young birds learn their songs by listening to adult tutors, much like human children acquire language. This process involves specific brain regions, including the high vocal center (HVC) and robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA), which are analogous to areas involved in speech production in humans.

In contrast, suboscines (e.g., flycatchers and tyrant birds) have less muscular control over the syrinx and rely on innate templates for their calls. Their vocalizations are genetically programmed rather than learned, meaning they develop normal songs even when raised in isolation.

Non-passerine birds also show diverse strategies. Parrots and hummingbirds, though not closely related to songbirds, independently evolved the ability to learn vocalizations. Owls produce low-frequency hoots suited for nocturnal communication, while woodpeckers often rely on drumming rather than vocalizations to signal territory.

| Bird Group | Vocal Learning? | Syrinx Complexity | Example Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oscine Passerines | Yes | High | Northern Cardinal, Nightingale |

| Suboscines | No | Moderate | Eastern Phoebe, Great Kiskadee |

| Parrots | Yes | High | African Grey Parrot, Macaw |

| Hummingbirds | Yes | Moderate-High | Rufous Hummingbird |

| Pigeons/Doves | No | Low | Mourning Dove |

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birdsong

Beyond biology, birdsong holds deep cultural and symbolic meaning across human societies. In many traditions, the dawn chorus—the collective singing of birds at sunrise—is associated with renewal, hope, and spiritual awakening. Ancient Greeks believed that the nightingale's song expressed sorrow and longing, inspired by the myth of Philomela. In Japanese culture, the cuckoo (hototogisu) symbolizes summer and impermanence, frequently appearing in haiku poetry.

The absence of vocal cords in birds does not diminish the emotional impact of their songs; if anything, it enhances the sense of wonder. Knowing that these intricate melodies arise from a completely different anatomical system underscores the diversity of life on Earth. Composers such as Olivier Messiaen incorporated actual bird calls into their works, transcribing species-specific patterns with scientific precision.

In modern times, birdsong is increasingly recognized for its psychological benefits. Studies show that exposure to natural sounds, especially bird vocalizations, reduces stress, improves concentration, and enhances mood. Urban planners now consider acoustic ecology when designing green spaces, aiming to support bird populations not just for biodiversity but for human well-being.

Practical Tips for Observing and Identifying Bird Sounds

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, understanding how birds produce sound can enhance field observation skills. Since birds lack vocal cords, recognizing the unique qualities of syrinx-generated sounds helps in species identification.

- Listen for frequency and modulation: Songbirds often produce rapid trills and pitch shifts due to fine syringeal control. Use apps like Merlin Bird ID or Song Sleuth to record and analyze calls in real time.

- Note the time of day: Many species sing most actively at dawn, when atmospheric conditions favor sound transmission and competition for auditory space is high.

- Observe body posture: Some birds inflate throat pouches or raise head feathers while vocalizing, indicating active use of the syrinx.

- Distinguish between calls and songs: Calls are typically short and functional (e.g., alarm, contact), while songs are longer, more complex, and used primarily in mating contexts.

- Use spectrograms: Visual representations of sound reveal subtle details invisible to the ear, such as overlapping harmonics or dual-voice production.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Vocalization

Despite growing scientific literacy, several myths persist about how birds make noise. One widespread misconception is that birds “sing” using lungs alone. While lung pressure drives airflow, the actual sound generation occurs in the syrinx, not the lungs themselves.

Another myth is that all birds learn their songs. As previously discussed, only certain groups—including oscines, parrots, and hummingbirds—are capable of vocal learning. Most bird species emit instinctive calls that do not require tutoring.

Some people assume that birds with louder calls must have larger syrinxes. However, volume depends more on muscle strength, air pressure, and resonance chambers in the trachea and beak than on syrinx size alone. For instance, the tiny Anna’s hummingbird produces loud chirps audible from dozens of meters away.

How Researchers Study the Avian Syrinx

Studying the syrinx presents technical challenges due to its small size and deep location. Scientists employ various methods, including high-speed endoscopy, X-ray videography, and electromyography (EMG) to measure muscle activity during vocalization.

In laboratory settings, researchers sometimes use denervation experiments—temporarily blocking nerve signals to syringeal muscles—to determine which muscles control specific aspects of sound. Other studies involve raising birds in soundproof environments to test the limits of innate versus learned vocal behavior.

Recent advances in 3D imaging and computational modeling have enabled virtual reconstructions of the syrinx, helping scientists simulate how different configurations affect sound output. These tools are especially useful for studying extinct species, where only skeletal remains are available.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can birds talk without vocal cords?

- Yes, parrots and some other birds mimic human speech using their syrinx and tongue movements, even though they lack vocal cords. Their ability stems from advanced neural control and vocal learning capacity.

- Do all birds have a syrinx?

- Most birds do, but there are exceptions. Flightless birds like ostriches and emus have reduced syrinxes and produce simpler vocalizations, often relying on non-vocal sounds like booming or hissing.

- Why don’t birds choke when they sing?

- Because the syrinx is located below the point where the trachea and esophagus diverge, food passes safely through the esophagus without interfering with sound production in the airway.

- Can birds sing in flight?

- Yes, many species such as skylarks and swifts sing while flying. Their efficient respiratory system allows continuous airflow needed for sustained vocalization during movement.

- Is the syrinx similar to vocal cords?

- While both produce sound via tissue vibration, the syrinx differs structurally and functionally. It is located lower in the respiratory tract and allows for greater acoustic flexibility, including simultaneous dual-tone production.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4