Yes, birds can hear, and their auditory abilities play a vital role in communication, navigation, predator detection, and mating behaviors. While birds lack external ears like mammals, they possess highly developed inner ear structures that allow them to detect a wide range of sound frequencies. The question do birds hear is commonly asked by bird enthusiasts, students, and curious observers trying to understand avian sensory perception. Unlike humans, birds rely on a combination of physical adaptations and behavioral cues to interpret sounds in their environment. Their hearing sensitivity varies across species, with some birds capable of detecting ultrasonic or infrasonic frequencies beyond human hearing range.

How Bird Hearing Differs from Mammalian Hearing

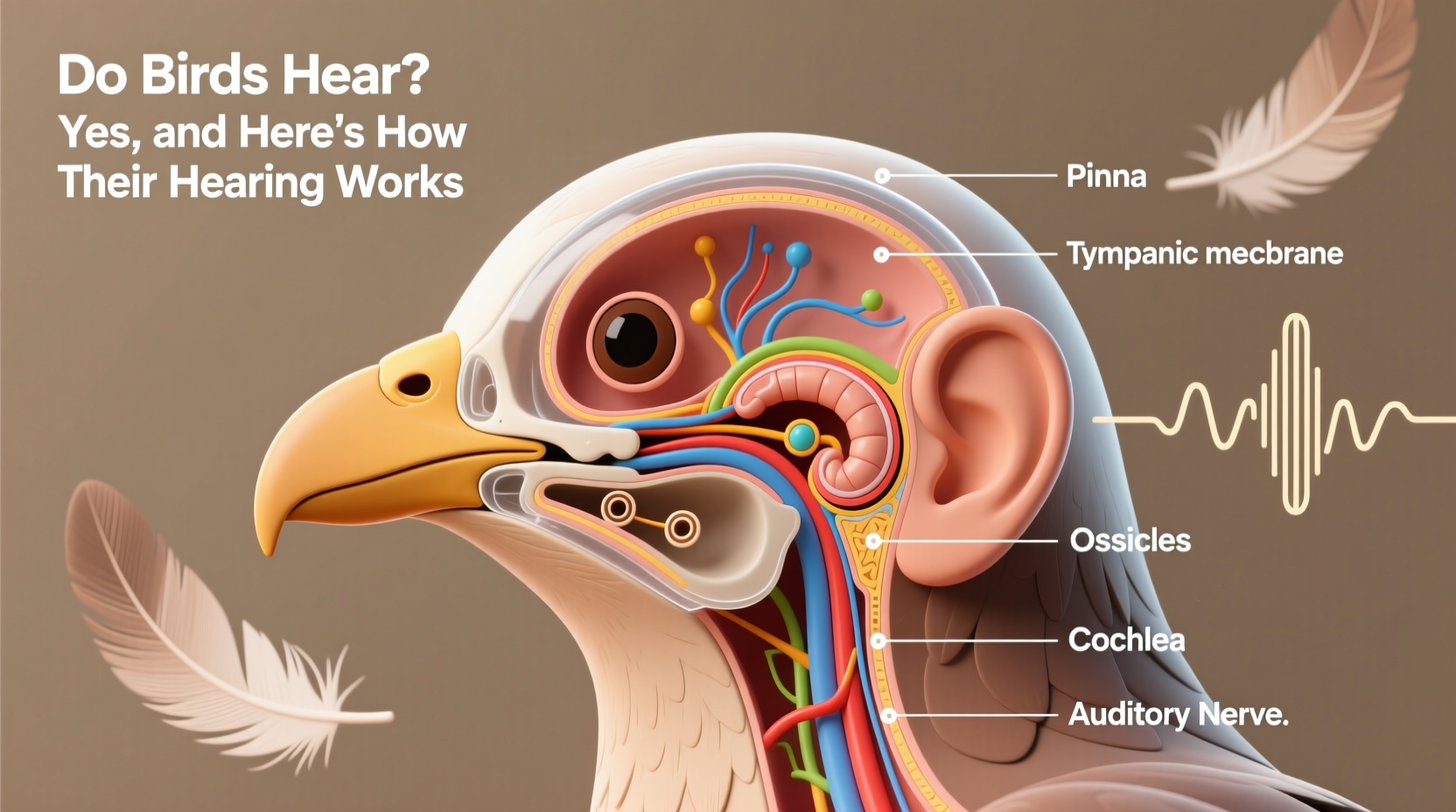

Birds do not have visible outer ears or pinnae, which are common in most mammals. Instead, their ear openings are located on the sides of their heads, usually hidden beneath specialized feathers known as auriculars. These feathers help direct sound into the ear canal while protecting it from wind and debris. Despite this structural difference, birds possess a cochlea—a fluid-filled, spiral-shaped structure in the inner ear—similar to that found in mammals. However, the avian cochlea is shorter and less coiled, which influences frequency discrimination.

One key distinction lies in neural processing. Birds process auditory information differently due to variations in brain structure. For example, songbirds have dedicated neural pathways for learning and producing complex vocalizations, a trait shared only with humans and a few other animals. This advanced auditory processing enables them to recognize subtle differences in pitch, rhythm, and timing—critical for mate selection and territorial defense.

Anatomy of Avian Hearing: From Ear Openings to Brain Processing

The avian auditory system consists of three main parts: the outer ear (represented by the ear opening), the middle ear (with the tympanic membrane and ossicles), and the inner ear (cochlea and auditory nerve). Sound waves enter through the ear opening and vibrate the eardrum. These vibrations are transmitted via small bones—the columella (equivalent to the mammalian stapes)—to the fluid in the cochlea. Hair cells within the basilar papilla (the bird equivalent of the organ of Corti) convert these mechanical signals into electrical impulses sent to the brain.

Interestingly, many birds exhibit asymmetrical ear placement, especially owls. Species such as the barn owl have one ear higher than the other, allowing them to pinpoint the location of prey based on minute differences in sound arrival time and intensity between ears. This adaptation enhances their ability to hunt in complete darkness using only auditory cues.

Frequency Range and Sensitivity Across Bird Species

Birds generally hear within a frequency range of 1,000 to 4,000 Hz, overlapping significantly with human hearing (20 Hz to 20,000 Hz). However, some species extend beyond this. For instance, pigeons can detect infrasound below 10 Hz, potentially aiding in long-distance navigation. Conversely, certain passerines may perceive higher frequencies up to 8,000–10,000 Hz, useful for interpreting high-pitched alarm calls.

Sensitivity also depends on ecological niche. Forest-dwelling birds often rely more on low-frequency sounds that travel better through dense foliage, while open-habitat species may use higher-pitched calls for long-distance communication. Urban birds, such as house sparrows and starlings, have been observed adjusting their songs to higher pitches to overcome low-frequency traffic noise—a phenomenon known as the Lombard effect.

| Bird Species | Hearing Range (Hz) | Notable Auditory Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Barn Owl | 200–12,000 | Asymmetrical ears for precise sound localization |

| Domestic Chicken | 50–4,000 | Highly sensitive to maternal calls; chicks respond pre-hatching |

| European Robin | 1,000–8,000 | Sings at dawn when background noise is minimal |

| Pigeon | 10–7,000 | Detects infrasound for navigation over long distances |

| Zebra Finch | 200–10,000 | Learns songs from tutors during critical developmental period |

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of Bird Hearing

Beyond biology, the idea of whether birds can hear has deep cultural resonance. In many indigenous traditions, birds are seen as messengers between realms, their ability to perceive unseen forces symbolized by acute hearing. For example, Native American folklore often portrays owls as wise beings who 'hear the whispers of the spirit world.' Similarly, in Celtic mythology, birds like ravens were believed to carry secrets on the wind, audible only to those attuned to nature’s rhythms.

In literature and poetry, references to birds hearing human thoughts or emotions reflect anthropomorphic interpretations of avian perception. Shakespeare used birdsong in plays like *Hamlet* and *A Midsummer Night's Dream* to signify both beauty and foreboding, suggesting an almost supernatural awareness. These symbolic associations persist today, reinforcing the enduring fascination with questions like do birds hear us when we talk?

Behavioral Evidence That Birds Respond to Sound

Observational and experimental studies confirm that birds react meaningfully to auditory stimuli. Parent-offspring recognition is one well-documented example. Nestling swallows and alpine swifts emit unique begging calls that parents distinguish from others in crowded colonies. Playback experiments show that adult birds will feed only those chicks whose calls match their own offspring’s signature.

Mating rituals further demonstrate sophisticated auditory processing. Male nightingales produce complex songs with over 200 different phrases, which females evaluate based on consistency, variety, and precision. Females prefer males with larger repertoires, indicating genetic fitness. Likewise, male canaries modulate song syntax seasonally, aligning vocal performance with hormonal changes tied to breeding cycles.

Predator avoidance also relies heavily on hearing. Black-capped chickadees emit distinct alarm calls depending on threat level—one call for aerial predators like hawks, another for ground-based threats like cats. Nearby birds instantly freeze or take cover upon hearing these signals, even if they haven’t seen the danger themselves.

Practical Implications for Birdwatchers and Conservationists

Understanding how birds hear enhances field observation techniques. Birdwatchers often use playback recordings to attract elusive species, but ethical considerations apply. Repeated use of calls can stress birds, disrupt nesting, or provoke aggressive territorial responses. Experts recommend limiting playback to brief intervals (<30 seconds) and avoiding use during breeding season unless part of formal research.

Noise pollution poses a growing threat to avian hearing and communication. Chronic exposure to urban noise can impair song transmission, reduce reproductive success, and alter habitat use. Studies show that great tits in noisy areas sing faster and at higher frequencies, potentially reducing mating effectiveness. Mitigation strategies include creating quiet zones near protected habitats and designing cities with green corridors that buffer sound.

Conservation programs increasingly incorporate acoustic monitoring. Automated recorders placed in forests and wetlands capture bird vocalizations, enabling researchers to assess biodiversity without visual sightings. Machine learning algorithms analyze thousands of hours of audio to identify species presence, population trends, and seasonal patterns—all made possible because birds not only hear but are heard.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Hearing

Despite scientific evidence, several myths persist. One widespread belief is that birds cannot hear at all because they don’t react visibly to loud noises. In reality, birds may remain still as a survival strategy; movement could attract predators. Another misconception is that pet birds ignore human speech. On the contrary, parrots, mynas, and corvids demonstrate remarkable vocal mimicry and comprehension, proving advanced auditory cognition.

Some people assume that flightless birds like ostriches have poor hearing. Yet, ostriches respond strongly to low-frequency rumbles, which travel far across savannas. They likely use infrasound to stay in contact with distant flock members. Similarly, waterfowl such as ducks and geese rely on honks and quacks to maintain group cohesion during migration, demonstrating robust hearing adapted to open environments.

Tips for Observing Bird Responses to Sound

- Use binoculars and patience: Watch for subtle head movements or posture changes when playing soft calls or making quiet sounds.

- Avoid sudden noises: Loud claps or shouts may scare birds away rather than test hearing.

- Visit early morning: Birds are most vocal and attentive at dawn, increasing chances of observing auditory responses.

- Try gentle whistling: Some species, like thrushes or wrens, may approach or respond with song if mimicked accurately.

- Record your observations: Note species, time, location, and behavior to track patterns over time.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can birds hear human voices?

- Yes, many birds, especially parrots and songbirds, can hear and distinguish human voices. Some learn to associate specific words with actions or rewards.

- Do birds hear ultrasound or infrasound?

- Most birds do not hear ultrasound (above 20,000 Hz), but some, like pigeons, can detect infrasound below 20 Hz, possibly aiding navigation.

- Are birds affected by loud music or construction noise?

- Yes, chronic noise can interfere with communication, increase stress hormones, and lead to abandonment of nesting sites.

- How do baby birds recognize their parents' calls?

- Chicks imprint on parental calls before or shortly after hatching, storing acoustic templates that guide recognition.

- Can deafness occur in birds?

- Yes, though rare, birds can suffer hearing loss due to infection, trauma, aging, or exposure to ototoxic drugs.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4