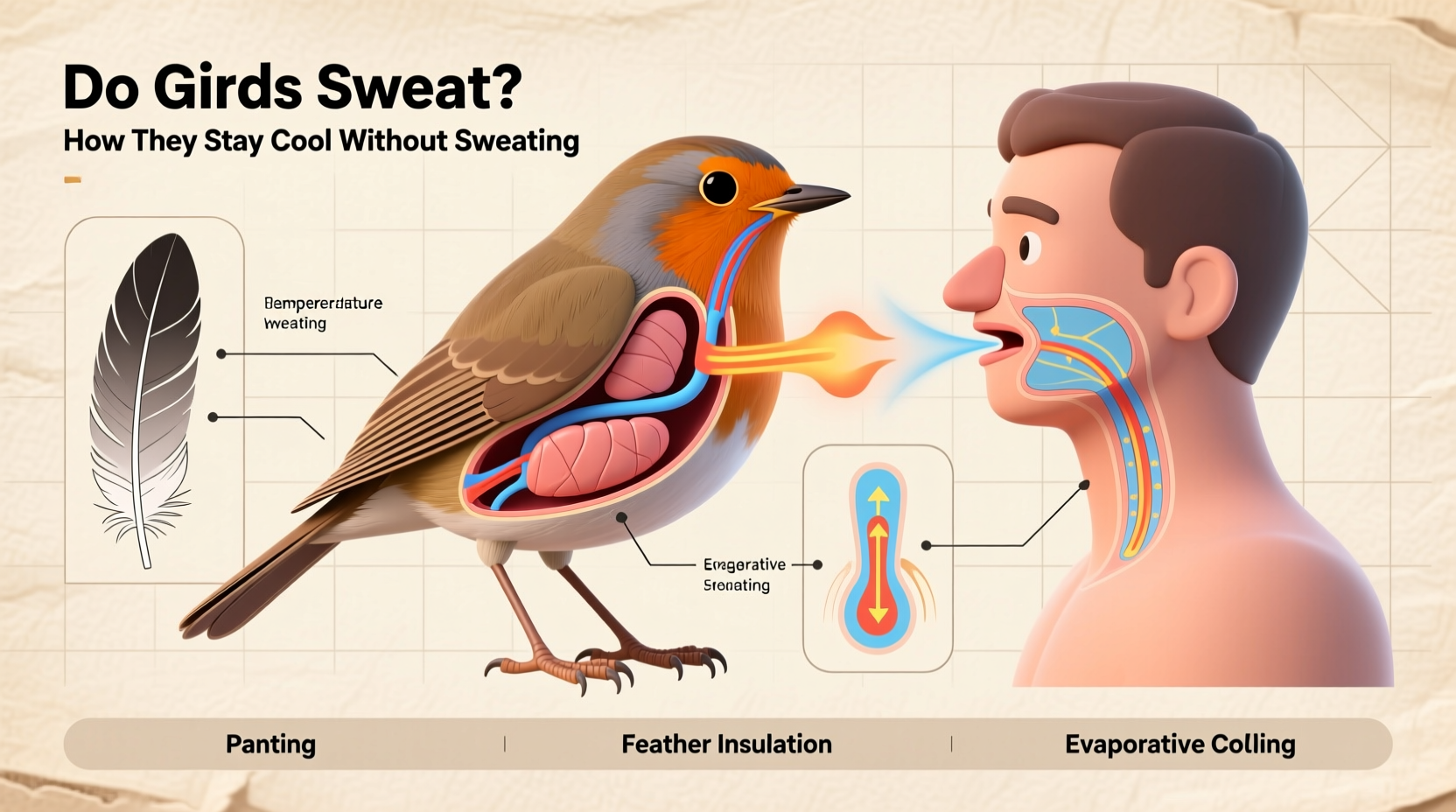

Birds do not sweat like mammals do. Instead of relying on sweat glands to cool down, birds use a variety of specialized physiological and behavioral mechanisms to regulate their body temperature. This key difference in thermoregulation means that while humans and many animals cool off through perspiration, birds rely on methods such as panting, gular fluttering, and seeking shade to avoid overheating. Understanding how birds regulate body temperature without sweating reveals fascinating adaptations shaped by evolution and environment.

The Biology Behind Why Birds Don’t Sweat

One of the most common questions in avian biology is: Do birds have sweat glands? The answer is no—birds lack eccrine and apocrine sweat glands entirely, which are the types responsible for moisture release in human skin. These glands play a major role in cooling the body during heat exposure, but birds evolved alternative strategies due to their unique anatomy and high metabolic rates.

Birds maintain a higher average body temperature than mammals—typically between 104°F and 110°F (40°C–43°C). With such intense internal heat production, especially during flight, effective cooling systems are essential. However, developing sweat glands would conflict with two critical features: feathers and waterproofing. Sweat could compromise feather integrity and insulation, making it counterproductive for survival.

Instead of sweating, birds dissipate heat primarily through unfeathered areas such as their legs, feet, beaks, and around the eyes. These exposed surfaces allow radiant heat loss. Additionally, blood vessels in these regions can dilate (vasodilation) to increase blood flow and enhance cooling—a process similar to how elephants use their ears.

Primary Cooling Methods Used by Birds

Since birds cannot sweat, they depend on several efficient alternatives to prevent hyperthermia, particularly in hot climates or during strenuous activity like flying under direct sunlight.

Panting and Respiratory Evaporation

One of the most visible ways birds cool themselves is through rapid, shallow breathing known as panting. Unlike mammals, whose panting mainly moves air over moist tissues in the mouth and tongue, birds utilize a more complex respiratory system involving air sacs and lungs. As they pant, moisture evaporates from the linings of their respiratory tract, effectively lowering body temperature.

This method, called respiratory evaporation, is highly effective but comes at a cost: excessive panting leads to water loss and increased risk of dehydration. Species living in arid environments, such as roadrunners or desert larks, must balance this carefully, often limiting activity during peak heat hours.

Gular Fluttering: Nature’s Avian Air Conditioner

A less widely known but equally important mechanism is gular fluttering. Found in birds like herons, pelicans, cormorants, and some raptors, this involves rapidly vibrating the thin skin of the throat (the gular region), much like a hummingbird’s wings. The motion increases airflow across moist membranes, promoting evaporation without expending large amounts of energy.

Gular fluttering is especially useful because it targets an area with rich vascularization and proximity to the respiratory system. It allows continuous cooling even when the bird is perched and unable to seek moving air. Observers may notice this behavior early in the morning or late afternoon when temperatures begin to rise.

Behavioral Adaptations to Avoid Overheating

Beyond physiology, birds employ smart behavioral tactics to manage heat:

- Seeking Shade: Many species retreat to shaded trees, rock crevices, or burrows during midday heat.

- Reduced Activity: Birds often minimize movement between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m., conserving energy and reducing internal heat generation.

- Postural Adjustments: Some birds adopt specific postures—such as holding wings slightly away from the body or orienting themselves to minimize sun exposure—to maximize heat dissipation.

- Bathing and Water Contact: Splashing in water helps conduct heat away from the skin and feathers. Even brief dips can offer significant relief.

Species-Specific Differences in Heat Regulation

Different bird species exhibit varying degrees of heat tolerance and cooling efficiency based on habitat, size, plumage, and lifestyle. For example:

| Species | Cooling Method | Habitat | Notable Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Great Blue Heron | Gular fluttering | Wetlands | Long neck enhances surface area for heat exchange |

| House Sparrow | Panting + shade-seeking | Urban areas | Highly adaptable to microclimates in cities |

| Emu | Feather positioning + panting | Australian outback | Uses feathers as insulation against external heat |

| Pigeon | Vasodilation in legs/beak | Global urban centers | Can tolerate wide temperature fluctuations |

| Hummingbird | Rapid respiration + torpor | Tropical forests | Enters temporary hibernation-like state at night |

These examples show how evolutionary pressures shape distinct cooling behaviors. Larger birds tend to retain more heat due to lower surface-area-to-volume ratios, so they often rely on multiple methods simultaneously. Smaller birds, though prone to faster heat gain, can also lose heat quickly and may use short bursts of activity followed by rest.

Misconceptions About Bird Sweating and Thermoregulation

Despite scientific clarity, several myths persist about whether birds sweat or feel heat the way humans do. Let’s address them directly:

- Myth: Birds sweat through their feet. While birds do lose some heat through unfeathered limbs, there are no sweat glands involved. The cooling effect comes purely from vasodilation and radiation, not moisture secretion.

- Myth: If a bird is breathing fast, it’s stressed or sick. Rapid breathing is often a normal response to heat. Only when accompanied by lethargy, drooping wings, or open-mouthed stillness should concern arise.

- Myth: All birds handle heat the same way. Tropical species are generally better adapted to high temperatures than temperate ones. Sudden heatwaves can be deadly for birds not acclimated to extreme warmth.

Implications for Birdwatchers and Conservationists

Understanding how birds stay cool has real-world implications for both amateur birdwatchers and wildlife professionals. During summer months, observers should take extra care not to disturb resting or panting birds, as interference can increase stress and accelerate dehydration.

Providing clean, shallow water sources in gardens or parks supports local populations by enabling bathing and drinking. Birdbaths should be placed in partial shade and cleaned regularly to prevent disease transmission. Avoid deep containers; most small birds prefer depths of less than 2 inches (5 cm).

For conservation efforts, climate change poses growing challenges. Rising global temperatures push many species beyond their thermal comfort zones. Migratory patterns, breeding times, and nesting success are all influenced by ambient heat levels. Monitoring changes in bird behavior during heat events provides valuable data for ecological studies.

How to Identify Heat Stress in Wild Birds

Recognizing signs of overheating can help determine if intervention is needed—especially in urban settings where escape from heat islands is limited. Key indicators include:

- Excessive panting even at rest

- Wings held away from the body (to expose unfeathered skin)

- Lethargy or inability to fly

- Open-mouth posture with little movement

- Loss of coordination

If you find a bird showing these symptoms, contact a licensed wildlife rehabilitator immediately. Do not attempt to force-feed water or place the bird in ice-cold water, as shock can occur. Instead, move it gently to a quiet, shaded area with access to fresh water and allow it to recover naturally if possible.

Cultural Symbolism of Heat and Birds Across Civilizations

Beyond biology, the relationship between birds and heat carries symbolic weight in various cultures. In ancient Egypt, the Bennu bird (a precursor to the phoenix myth) was associated with the sun and rebirth, rising anew from flames—a metaphor for regeneration through fire and transformation.

In Native American traditions, eagles and hawks are seen as messengers between earth and sky, thriving in high altitudes where sunlight is intense. Their ability to soar above scorching deserts symbolizes spiritual ascension and resilience.

In modern environmental discourse, birds serve as bioindicators of planetary health. The fact that they cannot sweat yet survive in extreme conditions underscores nature’s ingenuity—and humanity’s responsibility to protect fragile ecosystems threatened by rising temperatures.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can birds die from overheating?

- Yes, especially in prolonged heatwaves or confined spaces with poor ventilation. Young, injured, or elderly birds are most vulnerable.

- Do pet birds need special cooling in summer?

- Absolutely. Cage placement away from direct sunlight, access to mist sprays, and ceramic perches (which stay cooler) help domesticated birds regulate temperature.

- Is panting always a sign of heat in birds?

- Most commonly, yes—but panting can also indicate respiratory illness or stress. Context matters: check for other symptoms like nasal discharge or fluffed feathers.

- Why don’t birds sweat even though it seems efficient?

- Sweating would interfere with flight mechanics and feather function. Evolution favored lighter, drier solutions compatible with aerial life.

- Can birds adapt to hotter climates over time?

- Some species can adjust behaviorally or shift ranges, but rapid climate change may outpace adaptation, leading to population declines.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4