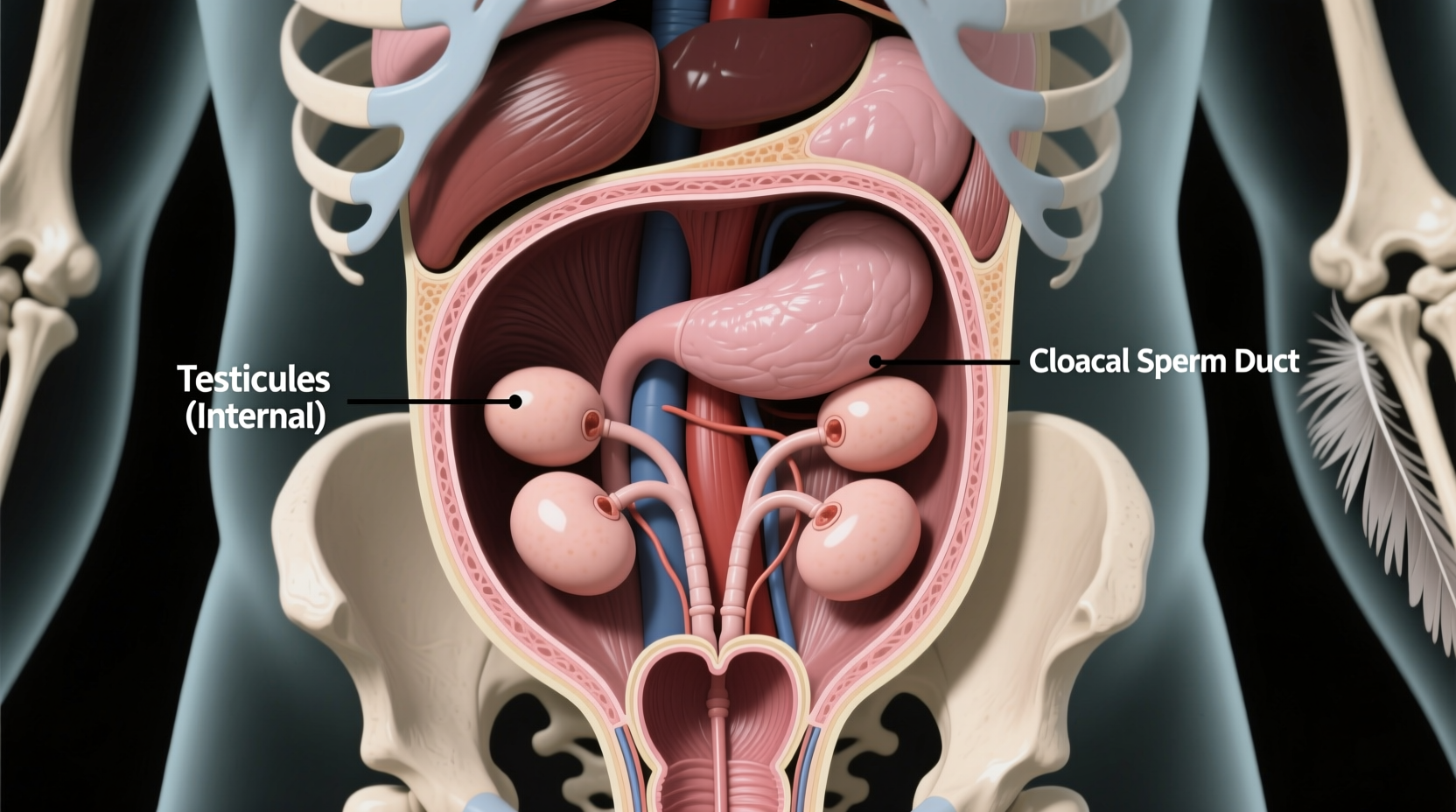

Yes, birds do have testicles, though they are internal and not externally visible like in many mammals. This common question—do birds have testicles—reflects a broader curiosity about avian reproductive anatomy and how it differs from that of other animals. Unlike mammals, male birds possess two testes located inside the abdominal cavity, near the kidneys. These organs produce both sperm and testosterone, playing a vital role in reproduction and seasonal behaviors such as singing and territoriality. A natural longtail keyword variant like 'do birds have testicles and where are they located' helps clarify this biological reality while addressing frequent search intent.

Avian Reproductive Anatomy: A Biological Overview

The internal placement of bird testicles is one of the defining features of avian biology. In nearly all bird species, males have paired testes that remain inside the body throughout their lives. These organs can vary significantly in size depending on the breeding season. For example, in small songbirds like sparrows or finches, the testes may be barely visible outside of mating periods but can increase in volume by up to 300% during spring and summer when reproductive activity peaks.

This seasonal fluctuation is hormonally regulated and directly tied to environmental cues such as day length (photoperiod), temperature, and food availability. The temporary enlargement allows for efficient sperm production without compromising flight performance—an essential evolutionary adaptation. Having external genitalia would create aerodynamic drag and potential injury risks, so natural selection favored internal reproductive structures.

During copulation, sperm travels through the cloaca—the single opening used for excretion and reproduction—in a process known as the "cloacal kiss." This brief contact transfers sperm from male to female and is sufficient for fertilization in most bird species. It's worth noting that only male birds have testes; females typically have just one functional ovary (usually the left), another weight-saving adaptation for flight.

Comparative Biology: Birds vs. Mammals

One reason people ask do birds have testicles stems from confusion caused by their lack of visible external sex organs. In contrast to most mammals, which retain their testes outside the body in a scrotum to maintain lower temperatures for optimal sperm development, birds keep theirs internally at core body temperature. This raises an important biological question: how do birds manage spermatogenesis under higher thermal conditions?

Research shows that avian testicular tissue has evolved unique cellular mechanisms to support sperm production at elevated temperatures. While mammalian sperm generally require cooling below core body temperature, birds have adapted biochemically to function efficiently despite the heat. This distinction underscores a major difference between avian and mammalian reproductive physiology.

Another key point of comparison involves sexual dimorphism. In many bird species, males and females look dramatically different (e.g., peacocks vs. peahens), yet these differences arise not from external genitalia but from plumage, size, and behavioral traits driven by hormones produced in the testes. Testosterone influences feather coloration, song complexity, aggression, and courtship displays—all critical components of mate selection.

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Testicle Location | Internal (abdominal cavity) | External (scrotum in most) |

| Temperature Regulation | High-temperature adapted | Cooling required |

| Reproductive Opening | Cloaca (shared) | Separate urethral & anal openings |

| Seasonal Size Change | Yes (dramatic) | Limited or none |

| Number of Functional Gonads in Females | One ovary (typically) | Two ovaries |

Symbols and Cultural Perceptions: The Hidden Nature of Bird Testicles

The invisibility of bird testicles has influenced cultural symbolism and myth across civilizations. Because most birds appear sexually neutral in appearance, especially outside breeding seasons, many ancient cultures associated them with purity, transcendence, or divine messengers. For instance, doves symbolize peace and spiritual renewal in Christianity, while eagles represent power and vision in Native American traditions.

Interestingly, the absence of visible reproductive organs contributed to the perception of birds as ethereal beings—detached from earthly desires. Yet biologically, the opposite is true: birds experience intense hormonal cycles and passionate mating rituals. The hidden nature of their testicles contrasts sharply with the flamboyance of their courtship behaviors, creating a duality between physical subtlety and behavioral intensity.

In some folklore, particularly in medieval Europe, there was even a mistaken belief that certain birds reproduced asexually or were born from mud or spontaneous generation due to their sudden appearances each spring. We now know these were migratory patterns, but the mystery surrounding bird reproduction—including questions like do birds have testicles—persisted until modern ornithology provided answers.

Observing Avian Behavior: Tips for Birdwatchers

Understanding bird reproductive anatomy enhances the观鸟 (birdwatching) experience, especially during breeding season. Observant birders can detect signs of active testicular function through changes in behavior and appearance. Here are practical tips:

- Listen for increased singing: Male birds sing more frequently and intensely when their testes are producing testosterone. Dawn chorus peaks in spring correlate with rising hormone levels.

- Watch for territorial disputes: Aggressive chasing, wing flicking, and vocal challenges indicate males defending nesting areas—a sign of reproductive readiness.

- Note plumage changes: Some species undergo pre-breeding molts that reveal brighter colors linked to testosterone surges.

- Observe courtship displays: From puffing chests to aerial dances, these behaviors are driven by internal hormonal shifts originating in the testes.

Birdwatchers should time their outings around early morning hours in spring (March to June in temperate zones) to witness peak reproductive activity. Using binoculars and field guides focused on breeding plumages and calls increases identification accuracy. Apps like eBird or Merlin Bird ID can help log sightings and track seasonal trends.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Reproduction

Despite scientific clarity, several myths persist about whether birds have testicles or how they reproduce. Let’s address them:

- Myth: Birds don’t have genitals. Truth: They do—both males and females have internal reproductive organs. The cloaca serves dual purposes, which may give the illusion of absence.

- Myth: Only roosters have testes. Truth: All reproductively mature male birds, from hummingbirds to ostriches, have testes.

- Myth: Birds lay eggs without mating. Truth: Unfertilized eggs (like those in commercial poultry farms) don't require mating, but wild birds typically need copulation for viable offspring.

- Myth: Female birds have two ovaries. Truth: Most have only one functional ovary, reducing body mass for flight efficiency.

These misconceptions often stem from superficial observation. Educators and conservationists emphasize hands-on learning and citizen science projects to correct false beliefs and promote deeper understanding of avian life.

Scientific Research and Conservation Implications

Studying bird testes provides valuable insights into environmental health. Scientists use testicular size and hormone levels as biomarkers for assessing the impact of pollutants, climate change, and habitat disruption. For example, exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) such as pesticides can alter testosterone production and impair fertility.

In urban environments, artificial light at night can disrupt photoperiod signals, leading to premature testicular growth and mistimed breeding. This mismatch with natural food cycles reduces chick survival rates. Conservation programs monitor these physiological indicators to evaluate ecosystem stability and guide policy decisions.

Veterinarians and aviculturists also rely on knowledge of avian reproductive systems when managing captive breeding programs for endangered species like the California condor or kākāpō. Ultrasound imaging and blood hormone assays allow non-invasive monitoring of testicular activity, ensuring optimal timing for pairing individuals.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Do all male birds have testicles?

- Yes, all sexually mature male birds have two internal testes located near the kidneys.

- Can you see a bird’s testicles?

- No, they are internal and not visible without dissection or medical imaging.

- When do bird testes grow larger?

- They enlarge significantly during the breeding season due to hormonal stimulation.

- Why don’t birds have external testes like mammals?

- External testes would interfere with streamlined flight; evolution favored internal placement with high-temperature sperm production.

- How does temperature affect bird sperm production?

- Birds have evolved biochemical adaptations that allow normal spermatogenesis at body temperatures around 40–42°C (104–107.6°F).

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4