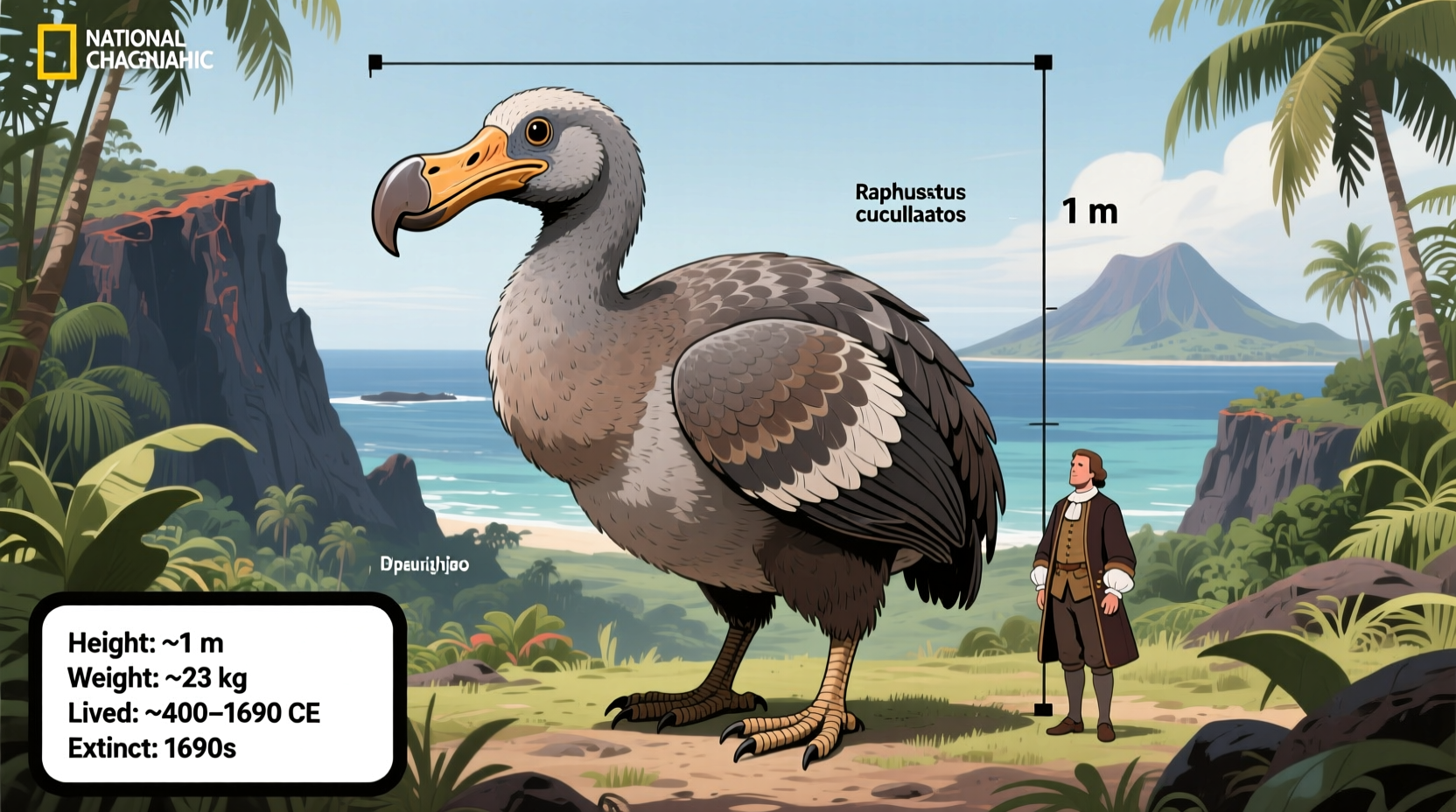

The dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) was a large, flightless bird that stood about 3 feet (approximately 1 meter) tall and weighed between 20 to 50 pounds (9 to 23 kg), with recent scientific estimates suggesting an average weight closer to 35 pounds (16 kg). Understanding how big is the dodo bird reveals not only its physical stature but also its unique evolutionary path on the island of Mauritius. This iconic species, now extinct, has become a symbol of human-driven extinction and ecological fragility.

Physical Characteristics of the Dodo Bird

The dodo was a member of the Columbidae family, making it a close relative of modern pigeons and doves. Despite its clumsy reputation, the dodo was well-adapted to its environment. Its size played a crucial role in its survival strategy before humans arrived.

On average, adult dodos reached a height of around 3 feet (1 meter) from beak to foot. Their bodies were robust and heavyset, built for walking rather than flying. The wings were small and underdevelopedâclear signs of evolutionary flightlessness due to the absence of natural predators on their native island.

Their most distinctive features included a large, hooked beak measuring up to 8 inches (20 cm) long, strong yellow legs, and a tuft of curly feathers at the rear resembling a tail. Contrary to popular cartoon depictions, the dodo was not inherently clumsy or unintelligent; its body structure was perfectly suited for foraging on the forest floor.

Weight Estimates and Scientific Reassessment

Historically, many accounts described the dodo as extremely overweight, sometimes estimating weights exceeding 50 pounds (23 kg). However, more recent paleontological studies based on skeletal reconstructions and comparisons with related species suggest a leaner build.

A 2011 study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B analyzed dodo bones and concluded that the bird likely weighed around 35 pounds (16 kg) in lifeâstill substantial, but not obese. This reassessment helps correct the long-standing myth that the dodo was grossly overweight, which may have contributed to misconceptions about its behavior and extinction.

These updated insights into how big is the dodo bird reflect improved methodologies in fossil analysis and comparative anatomy. Scientists now use 3D modeling and density estimates from extant relatives like the Nicobar pigeon to reconstruct soft tissue and body mass more accurately.

Habitat and Evolutionary Background

The dodo evolved in isolation on the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, located east of Madagascar. With no land mammals or significant predators, the selective pressures that typically maintain flight capability were absent. Over thousands of years, the dodo lost the ability to fly, investing energy instead into larger body size and strong legs for ground movement.

This process, known as insular gigantism, explains why some island species grow larger than their mainland counterparts. In the case of the dodo, increased size may have helped regulate body temperature and allowed it to consume a wide variety of plant foods, including fruits, seeds, and possibly shellfish.

Fossil evidence suggests the dodo lived primarily in the forests of Mauritius, where it played a key role in seed dispersal for several native tree species. One such example is the tambalacoque tree (Sideroxylon grandiflorum), once believed to depend solely on the dodo for germinationâa theory later debated but still illustrative of the birdâs ecological importance.

Discovery and Human Interaction

The first recorded encounter with the dodo occurred in 1598 when Dutch sailors landed on Mauritius during a voyage to the East Indies. They named the bird âdodo,â possibly derived from the Dutch word dodaars, referring to a plump, short-tailed bird, or from âdodoor,â meaning sluggish.

Sailors found the birds easy to catch due to their lack of fear of humansâan evolutionary trait that proved fatal. The dodo became a convenient source of fresh meat for passing ships, although reports vary on the taste, with some describing it as tough and unpalatable.

However, direct hunting was not the sole cause of extinction. More devastating were the invasive species introduced by humans: rats, pigs, monkeys, and cats. These animals raided dodo nests, ate eggs, and competed for food resources. Combined with habitat destruction from deforestation, these factors led to a rapid population decline.

Timeline of Extinction

The last widely accepted sighting of a live dodo was in 1662, less than 70 years after its discovery by Europeans. By the late 17th century, the species was goneâa remarkably swift extinction event in geological terms.

For decades, there was debate over whether the dodo truly existed or was a myth. It wasnât until the 19th century, when scientists began examining preserved remainsâincluding a skull and partial skeleton housed at Oxford Universityâthat the dodoâs existence was confirmed beyond doubt.

Today, researchers continue to analyze subfossil bones collected from swamp deposits on Mauritius. These findings help refine our understanding of the dodoâs biology, growth patterns, and environmental interactions.

Cultural Significance and Symbolism

Beyond its biological attributes, the dodo holds deep cultural significance. It has become a global symbol of extinction, obsolescence, and human impact on nature. Phrases like âdead as a dodoâ entered common usage to describe anything outdated or obsolete.

The bird gained further fame through Lewis Carrollâs Aliceâs Adventures in Wonderland (1865), where a comical, melancholic dodo appears in the Caucus Race. While Carrollâs portrayal reinforced certain stereotypes, it also cemented the dodoâs place in popular culture.

In Mauritius today, the dodo is a national emblem. It appears on the coat of arms, currency, and tourism materials, serving both as a reminder of ecological loss and a point of national identity.

Modern Research and Rediscovery Efforts

Recent advances in genetics have opened new avenues for studying the dodo. In 2022, scientists successfully sequenced nearly the entire genome of the dodo using DNA extracted from a 350-year-old specimen at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

This breakthrough allows researchers to explore the genetic basis of flightlessness, metabolic adaptations, and evolutionary relationships within the pigeon family. Such work contributes to broader efforts in conservation biology, offering insights into how isolated species adaptâand fail to adaptâto sudden environmental changes.

While de-extinction technologies remain speculative, the dodoâs genome could theoretically be used in future cloning attempts, similar to proposals for the woolly mammoth. However, ethical and ecological concerns dominate discussions around reviving extinct species.

Where to See Dodo Remains Today

No complete dodo specimen exists, but several museums house original bones and fragments:

- Oxford University Museum of Natural History: Holds the most famous remains, including a head and foot.

- Natural History Museum, London: Displays a dodo skull and leg bones. \li>Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris: Features a lower jawbone.

- Indian Ocean Islands Museum, Mauritius: Exhibits subfossil bones found locally.

Many institutions also offer digital scans and 3D models online, allowing researchers and the public to examine dodo anatomy in detail.

| Feature | Average Measurement | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Height | 3 feet (1 meter) | Measured from head to foot |

| Weight | 35 lbs (16 kg) | Recent estimates; range: 20â50 lbs |

| Beak Length | 8 inches (20 cm) | Strong, curved, adapted for fruit-eating |

| Wing Size | Very small | Flightless; wings not functional |

| Leg Color | Yellow | Thick, powerful legs for walking |

Common Misconceptions About the Dodo

Several myths persist about the dodo bird, often stemming from outdated illustrations and exaggerated sailor tales:

- The dodo was stupid. There is no evidence supporting low intelligence. Like other pigeons, it likely had adequate cognitive abilities for survival in its niche.

- It was slow and clumsy. While flightless, its leg structure indicates it was capable of steady locomotion through dense forest.

- Humans hunted it to extinction directly. Hunting played a role, but invasive species and habitat loss were greater contributors.

- All dodos were massively overweight. Early drawings depicted fat birds, but modern science favors a more athletic build.

Lessons from the Dodoâs Extinction

The story of the dodo offers critical lessons for modern conservation. It stands as one of the first documented cases of human-caused extinction, highlighting the vulnerability of island ecosystems.

Species that evolve without predators often lack defensive behaviors or physical adaptations to survive sudden threats. When humans introduce invasive speciesâeven seemingly harmless ones like ratsâthe consequences can be catastrophic.

Conservationists today apply these lessons to protect endangered island birds, such as the kakapo in New Zealand or the Galápagos rail. Measures include predator-free sanctuaries, breeding programs, and strict biosecurity protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions

- How big was the average dodo bird?

- The average dodo stood about 3 feet (1 meter) tall and weighed approximately 35 pounds (16 kg), though estimates range from 20 to 50 pounds depending on the individual and historical source.

- Was the dodo really as fat as it looks in old drawings?

- No. Many early illustrations exaggerated the dodoâs size and fatness. Modern research based on bone structure suggests a more streamlined, muscular build suited to its environment.

- Could the dodo fly?

- No, the dodo was completely flightless. Its wings were too small and weak to support flight, a result of evolving in a predator-free environment.

- Why did the dodo go extinct so quickly?

- The dodo went extinct due to a combination of hunting, habitat destruction, and predation by invasive species like rats and pigs introduced by humans.

- Is there any chance the dodo could come back?

- While its full genome has been sequenced, bringing the dodo back via de-extinction technology remains highly speculative and faces major scientific and ethical challenges.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4