Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, spreads primarily through direct contact between infected and healthy birds, as well as through contaminated environments. One of the most common ways bird flu spreads is via respiratory secretions, saliva, and feces from infected birds, which can contaminate water sources, feed, cages, and farming equipment. A natural long-tail keyword variation that captures this process is how does bird flu spread from wild birds to domestic poultry. Understanding this transmission pathway is essential for preventing outbreaks in both commercial farms and backyard flocks. While most strains affect only birds, some—like H5N1 and H7N9—can infect humans, typically through close contact with infected birds or contaminated surfaces.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Types and Strains

Bird flu is caused by Type A influenza viruses, which are categorized based on combinations of surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, but the most concerning for bird populations and public health are H5 and H7. These viruses are further classified into low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) and high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). LPAI may cause mild symptoms such as ruffled feathers or reduced egg production, while HPAI can lead to sudden death in entire flocks with mortality rates approaching 100%.

The current global concern centers around the H5N1 strain, which has evolved into multiple clades since its emergence in 1996. The 2.3.4.4b clade, dominant since 2020, has shown unprecedented spread across continents, affecting not only poultry but also wild bird populations and even marine mammals. This widespread circulation increases opportunities for human exposure and potential viral adaptation.

Primary Transmission Routes Among Birds

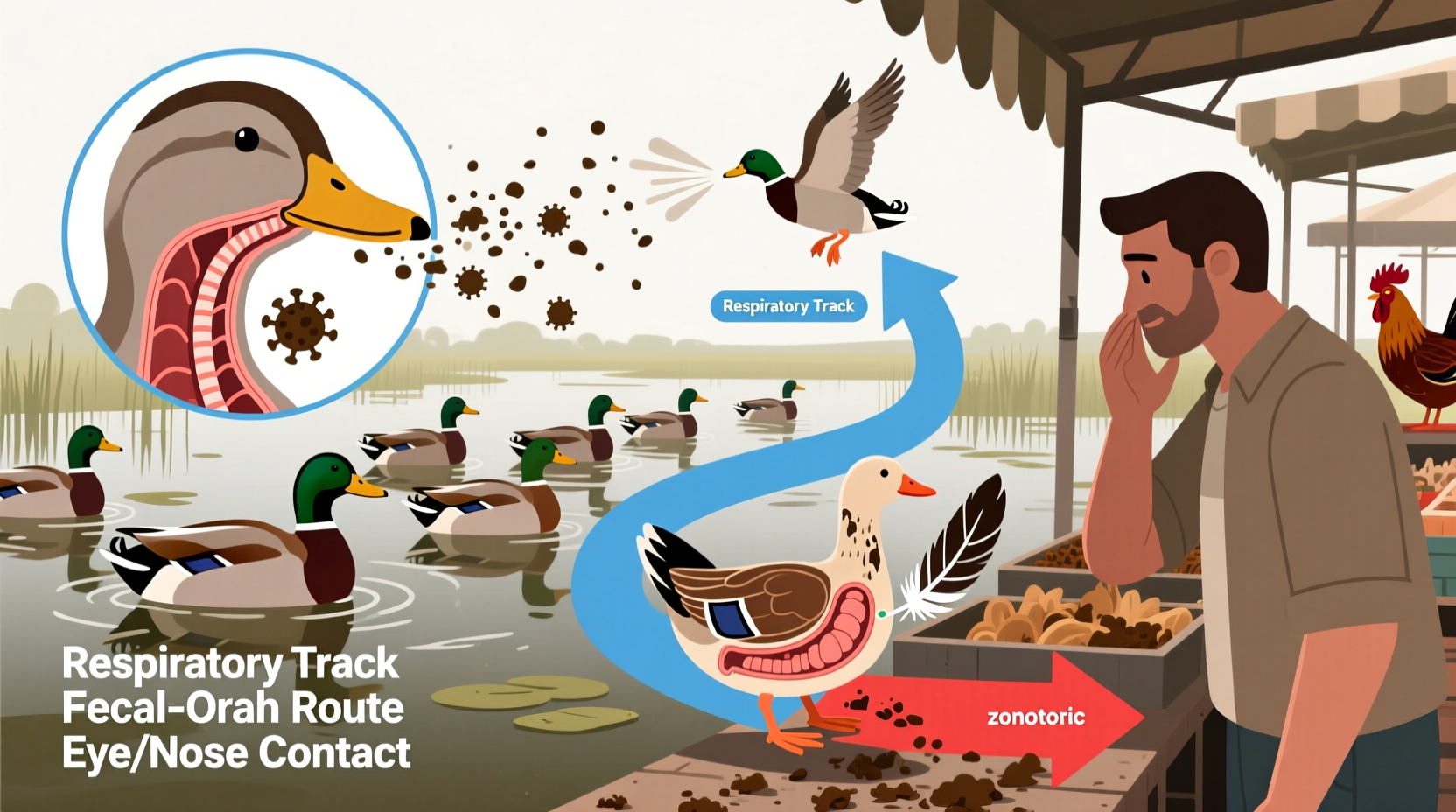

The primary way bird flu spreads among birds is through direct bird-to-bird contact. Infected individuals shed large amounts of virus in their droppings and respiratory secretions. Healthy birds become infected when they inhale aerosolized particles or ingest contaminated material. Waterfowl, especially ducks and geese, often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent transmitters within migratory flyways.

Indirect transmission occurs when the virus persists in the environment. The avian influenza virus can remain infectious:

- Up to 30 days in cold water (below 4°C)

- Several days in feces at room temperature

- Weeks on contaminated surfaces like soil, crates, or boots

This environmental resilience means that shared water sources, such as ponds or lakes used by both wild and domestic birds, serve as major hotspots for transmission. Backyard poultry owners who allow their birds access to open water bodies significantly increase the risk of introducing the virus into their flocks.

Role of Wild Birds in Geographic Spread

Migratory birds play a critical role in the long-distance spread of bird flu. Species such as swans, gulls, and shorebirds travel thousands of miles along established migration routes, carrying the virus across international borders. Surveillance data from Europe, North America, and Asia show seasonal spikes in outbreaks coinciding with spring and fall migrations.

In 2022, for example, H5N1 was detected in over 50 countries, largely linked to movements of wild birds. In the United States, the USDA confirmed cases in commercial and backyard flocks across 47 states during the 2022–2023 season—the largest outbreak in U.S. history. Genetic sequencing revealed that the virus strain matched those circulating in wild birds from Eurasia, confirming intercontinental transmission via migration.

It’s important to note that not all wild birds are equally susceptible. Passerines (perching birds) and raptors have increasingly tested positive in recent years, suggesting the virus is adapting to new hosts. This expansion raises concerns about ecosystem impacts and increased spillover risks.

Transmission to Humans: How Rare but Serious Infections Occur

While bird flu does not spread easily from birds to humans, sporadic infections do occur. Most human cases result from prolonged, unprotected exposure to infected birds or contaminated environments. Common scenarios include:

- Killing, defeathering, or preparing infected poultry for cooking

- Working in live bird markets with poor ventilation and hygiene

- Cleaning coops or handling sick birds without protective gear

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that since 2003, there have been over 900 confirmed human cases of H5N1 globally, with a fatality rate exceeding 50%. However, sustained human-to-human transmission remains extremely rare. When limited person-to-person spread has occurred, it typically involved close family members caring for an ill relative under intense exposure conditions.

A notable case in 2024 involved a dairy worker in Texas who contracted H5N1 after contact with infected cattle—an unusual development indicating possible mammalian adaptation. This event underscored the need for enhanced surveillance beyond poultry and highlighted emerging pathways such as cross-species transmission in agricultural settings.

Farm-Level Risk Factors and Biosecurity Gaps

Large-scale poultry operations and small backyard flocks face different but overlapping risks. Industrial farms may experience rapid spread due to high bird density, while backyard keepers often lack awareness of biosecurity practices. Key risk factors include:

- Lack of physical barriers between wild and domestic birds

- Sharing equipment or workers between farms without disinfection

- Purchasing birds from unregulated markets

- Feeding raw slaughter waste or untreated kitchen scraps to poultry

In regions with weak veterinary infrastructure, delayed reporting and inadequate culling contribute to wider dissemination. In contrast, countries like the Netherlands and South Korea enforce strict zoning, movement controls, and vaccination programs (where approved), helping contain outbreaks more effectively.

| Transmission Route | Risk Level (Birds) | Risk Level (Humans) | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct bird-to-bird contact | Very High | Low | Isolate new birds; avoid mixing flocks |

| Contaminated water sources | High | Moderate | Use clean, covered water supplies |

| Contact with wild bird droppings | High | Low | Secure housing; prevent access to wild areas |

| Handling infected birds (no PPE) | N/A | High | Wear gloves, masks, wash hands thoroughly |

| Consuming properly cooked poultry | N/A | None | No action needed—heat kills virus |

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Flu Transmission

Several myths persist about how bird flu spreads, leading to unnecessary fear or complacency. For instance:

- Myth: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and pasteurized eggs pose no risk. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F). - Myth: Pet birds are safe from wild bird flu.

Fact: Canaries, parrots, and other cage birds are susceptible if exposed. Indoor housing with filtered air reduces risk. - Myth: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Turkeys, guinea fowl, quail, and even ostriches can be infected. Some songbirds and raptors have died from H5N1 in recent outbreaks.

Prevention Strategies for Poultry Owners and the Public

Effective prevention requires a multi-layered approach. For poultry farmers and backyard flock owners, key actions include:

- Biosecurity measures: Install footbaths with disinfectant, restrict visitor access, and clean tools regularly.

- Housing modifications: Keep birds indoors during active outbreak periods, especially in regions with reported wild bird infections.

- Surveillance: Report sudden deaths or illness in birds to local veterinary authorities immediately.

- Vaccination: Where permitted and available, use vaccines in coordination with government programs to reduce viral load, though they don’t always prevent infection.

For the general public, avoiding contact with sick or dead birds is crucial. If you find a dead bird, do not touch it. Instead, report it to your local wildlife agency. Hunters should wear gloves when handling game birds and ensure thorough cooking of harvested meat.

Global Surveillance and Response Systems

Organizations such as the WHO, FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), and OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) coordinate global monitoring efforts. National agencies like the CDC in the U.S. and DEFRA in the UK issue regular updates on outbreak zones and risk levels. These systems rely on early detection, rapid diagnostics, and transparent reporting to slow the spread.

Real-time tracking platforms, such as the Animal Disease Information System (ADIS) and EMPRES-i (FAO), map outbreaks and help predict high-risk periods. During peak migration seasons—typically March–April and September–November—authorities intensify surveillance in wetlands and poultry-dense regions.

What to Do If an Outbreak Is Reported Nearby

If bird flu is confirmed in your area, take immediate steps:

- Stop all movement of birds on or off your property.

- Enhance biosecurity: disinfect shoes, vehicles, and equipment before entering bird areas.

- Contact your veterinarian or state animal health official for guidance.

- Monitor your birds daily for signs of illness: lethargy, swelling, purple discoloration, or decreased appetite.

- Prepare for possible depopulation orders if infection is suspected.

Compensation programs may exist for farmers who lose flocks due to government-mandated culling, but eligibility varies by country and farm size.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Ongoing research focuses on understanding how bird flu evolves to infect new species and whether it could gain efficient human-to-human transmission. Scientists are studying viral mutations in the HA protein that affect host cell binding, particularly changes that allow the virus to attach to human upper respiratory tract cells.

Vaccine development for both birds and humans continues, though challenges remain due to the virus’s rapid mutation rate. Universal flu vaccines targeting conserved regions of the virus are being explored as a long-term solution.

FAQs About How Bird Flu Spreads

- Can you get bird flu from eating eggs?

- No, you cannot get bird flu from eating eggs that are properly cooked. The virus is killed by heat, so boiling, frying, or baking eggs to an internal temperature of 70°C or higher eliminates any risk.

- Do all birds carry bird flu?

- No, not all birds carry the virus. While many wild waterfowl can harbor low-pathogenic strains asymptomatically, most birds—including pet and backyard poultry—are free of infection unless exposed.

- How long can bird flu survive in the environment?

- The virus can survive for up to 30 days in cold water, several days in feces at room temperature, and weeks on porous surfaces like wood or fabric if kept cool and moist.

- Can cats and dogs get bird flu?

- Yes, though rare. Domestic cats have been infected after eating raw infected birds. Dogs are less susceptible but can potentially contract the virus through close contact with sick poultry.

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

- There is no widely available commercial vaccine for the general public, but candidate vaccines exist for stockpiling in case of a pandemic. Seasonal flu vaccines do not protect against avian influenza.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4