Bird flu, or avian influenza, spread primarily through the movement of infected birds, both wild and domestic, as well as through contaminated environments and human-assisted transmission. The most significant outbreaks, particularly those involving the highly pathogenic H5N1 strain, have followed migratory bird routes, allowing the virus to cross continents. A key factor in how did bird flu spread across poultry farms and wild populations is the shedding of the virus in bird feces, saliva, and nasal secretions, which contaminates water sources, equipment, and clothing. This natural transmission pathway—combined with global trade in live birds and inadequate biosecurity measures—has enabled rapid dissemination, especially since the early 2000s.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Virus Types

Avian influenza is caused by Type A influenza viruses, which are categorized based on combinations of surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 16 H subtypes and 9 N subtypes that commonly infect birds. Among these, the H5 and H7 strains are of greatest concern due to their potential to mutate into highly pathogenic forms.

The first recorded outbreak of avian influenza dates back to 1878 in Italy, where it was referred to as “fowl plague.” However, modern understanding of how bird flu spreads began in the late 20th century. The current global concern stems largely from the emergence of the H5N1 strain in 1996 in Guangdong, China, among geese. By 1997, it had infected humans in Hong Kong, marking the first known case of direct bird-to-human transmission.

Since then, multiple strains—including H5N8, H7N9, and H5N6—have emerged, each with different transmission dynamics. While low-pathogenic strains may cause mild illness in birds, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) can result in mortality rates approaching 100% in poultry flocks within days.

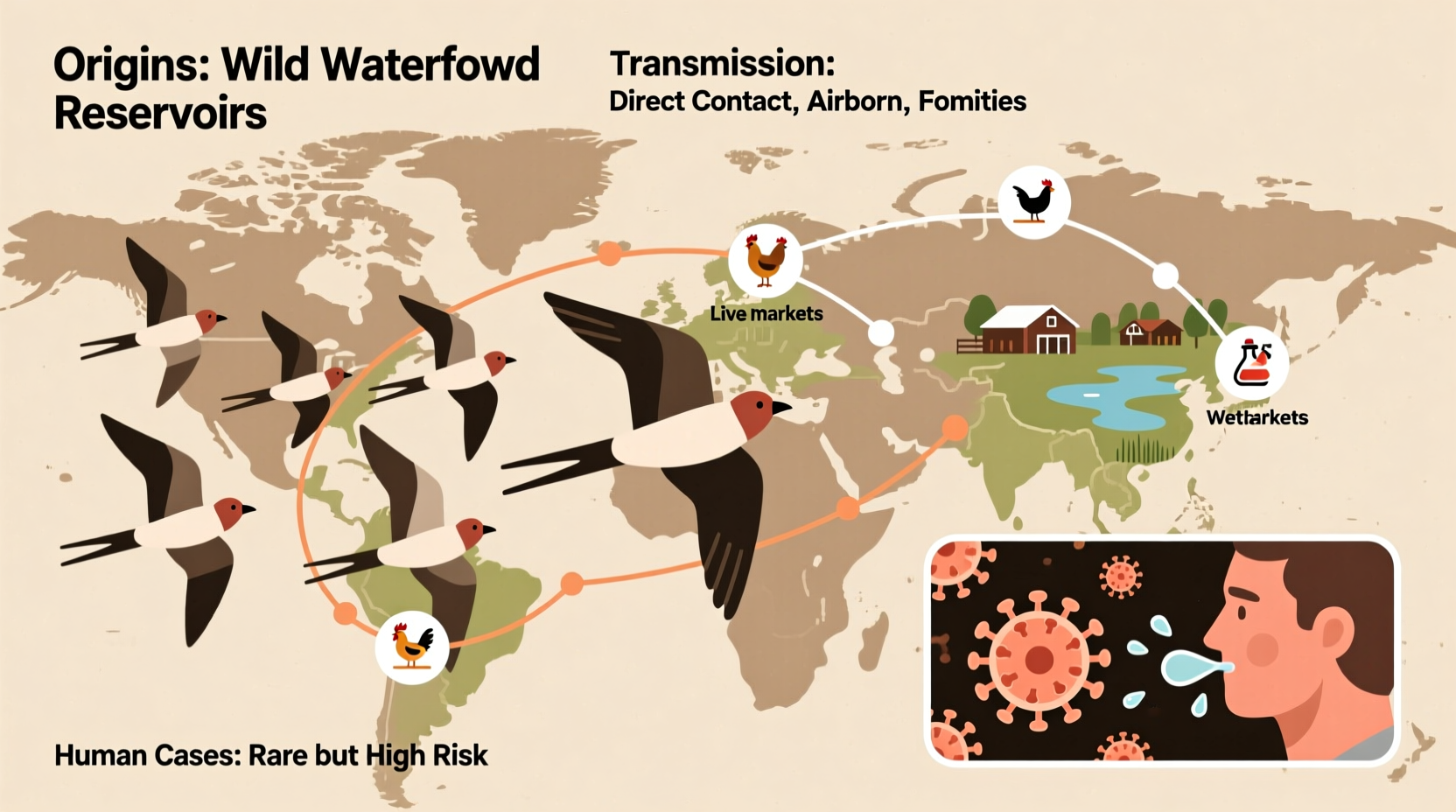

Migratory Birds and Global Spread

One of the primary mechanisms explaining how did bird flu spread across international borders involves wild migratory birds, particularly waterfowl such as ducks, geese, and swans. These species often carry the virus asymptomatically, shedding it in their droppings into lakes, ponds, and wetlands used by other birds.

Migratory flyways—such as the East Asian-Australasian, Black Sea-Mediterranean, and Americas flyways—serve as highways for disease transmission. For example, genetic analysis has shown that H5N1 spread from Asia to Europe via Siberian breeding grounds used by migratory ducks. In 2005, an outbreak at Qinghai Lake in China resulted in the deaths of over 6,000 migratory birds and marked a turning point in the global dispersion of the virus.

Similarly, in 2014, the H5N8 strain was introduced into North America through Alaska, likely carried by birds migrating from East Asia. From there, it spread rapidly across commercial poultry operations in the U.S. Midwest during 2015, leading to the culling of nearly 50 million birds—the largest animal health emergency in U.S. history at the time.

Role of Poultry Farming and Biosecurity Failures

While wild birds initiate many outbreaks, the amplification and sustained spread of bird flu often occur within commercial and backyard poultry operations. High-density farming practices create ideal conditions for viral transmission. Once introduced, the virus can move quickly between coops through airborne particles, shared water systems, or farm workers' boots and clothing.

In countries with limited veterinary oversight or poor biosecurity protocols, the risk is significantly higher. For instance, live bird markets in parts of Southeast Asia and China have been identified as hotspots for virus mixing and reassortment, where different strains can combine to form new variants.

Additionally, the practice of raising ducks and chickens together—common in some rural areas—increases cross-species transmission risks. Ducks may carry the virus without showing symptoms, silently infecting more susceptible chicken populations.

Human-Mediated Transmission Pathways

People play a crucial role in how did bird flu spread beyond natural ecological boundaries. The legal and illegal trade in live birds—whether for food, pets, or fighting—has repeatedly introduced the virus into new regions. For example, outbreaks in Nigeria in 2006 were traced to imported poultry from Asia.

Transport vehicles, cages, and farming equipment that are not properly disinfected can carry the virus over long distances. Even well-intentioned actions—like rescuing sick wild birds—can inadvertently contribute to local spread if proper quarantine procedures aren’t followed.

Moreover, climate change and habitat loss are altering bird migration patterns, bringing wild and domestic birds into closer contact than ever before, further increasing spillover risks.

Timeline of Major Outbreaks and Geographic Expansion

The global progression of bird flu reflects a pattern of incremental spread driven by both natural and human factors:

- 1996–1997: Emergence of H5N1 in China; first human cases in Hong Kong.

- 2003–2005: Regional spread across Southeast Asia, affecting countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia.

- 2005–2006: Spread to Europe, Africa, and the Middle East via migratory birds and trade.

- 2014–2015: Introduction of H5N8 into North America; massive U.S. poultry outbreak.

- 2020–2024: Unprecedented panzootic of H5N1 affecting wild birds and poultry globally, including first detections in South America and Antarctica.

Notably, since 2021, clade 2.3.4.4b of H5N1 has become dominant worldwide, causing widespread mortality in seabird colonies, including puffins, gannets, and albatrosses—an alarming shift indicating increased environmental persistence and host range expansion.

Impact on Wildlife, Agriculture, and Public Health

The consequences of bird flu extend far beyond individual bird deaths. Ecologically, mass die-offs threaten biodiversity, especially among endangered or island-bound species with no prior exposure or immunity.

In agriculture, outbreaks lead to massive economic losses due to culling, trade restrictions, and reduced consumer confidence. Countries that export poultry products face immediate embargoes when outbreaks are reported, creating strong incentives—sometimes counterproductive—for underreporting.

From a public health standpoint, while human infections remain rare, they are often severe. Since 2003, the World Health Organization has recorded over 900 human cases of H5N1, with a fatality rate exceeding 50%. Most cases involve close contact with infected birds, but any sustained human-to-human transmission would pose a pandemic threat.

Prevention and Control Measures

Controlling the spread of bird flu requires a multi-pronged approach:

- Biosecurity on Farms: Restrict access to poultry houses, use dedicated clothing and footwear, disinfect equipment, and prevent contact with wild birds.

- Surveillance Programs: Regular testing of wild bird populations and domestic flocks helps detect outbreaks early.

- Vaccination: Used selectively in some countries, though concerns about vaccine-derived virus circulation and interference with diagnostics limit widespread adoption.

- Public Awareness: Educating farmers, hunters, and the public about safe handling practices reduces spillover risk.

- International Cooperation: Sharing virus data through networks like OFFLU (OIE/FAO Network on Animal Influenza) improves global response coordination.

For backyard flock owners, simple steps like enclosing coops, avoiding shared water sources with wild birds, and reporting sick or dead birds to authorities can make a significant difference.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu Transmission

Several myths persist about how did bird flu spread, potentially undermining prevention efforts:

- Myth: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Over 100 bird species have tested positive, including raptors, songbirds, and marine birds. - Myth: Cooking poultry spreads the virus.

Fact: Properly cooked meat (165°F internal temperature) kills the virus; risk comes from handling raw infected meat. - Myth: Humans easily catch bird flu.

Fact: Human cases are rare and typically require prolonged, close contact with infected birds. - Myth: The virus spreads rapidly through the air like human flu.

Fact: It spreads mainly through direct contact or contaminated surfaces, not long-range aerosols.

Regional Differences in Response and Risk Levels

Responses to bird flu vary widely depending on national resources and agricultural structure. In high-income countries like the U.S. and Canada, rapid detection systems and compensation programs for culled birds encourage timely reporting. In contrast, low-resource settings may lack diagnostic labs or financial support for farmers, leading to delayed responses.

In Europe, the EU mandates strict surveillance and movement controls during outbreaks. Meanwhile, in parts of Africa and South Asia, informal poultry markets and free-ranging birds complicate containment.

Seasonal patterns also affect risk: outbreaks tend to peak during fall and winter in temperate zones, coinciding with bird migration and cooler temperatures that prolong virus survival in the environment.

How to Stay Informed and Take Action

If you’re a birdwatcher, farmer, or concerned citizen, staying updated is essential. Reliable sources include:

- National veterinary services (e.g., USDA APHIS in the U.S.)

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) reports

- CDC and WHO public health advisories

- Local wildlife agencies and bird conservation groups

Report unusual bird deaths—especially clusters of waterfowl or raptors—to local authorities. Avoid touching dead or sick birds without gloves and masks. Hunters should follow state guidelines on cleaning game and avoid hunting in outbreak zones.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did bird flu spread to mammals?

Recent cases in foxes, seals, sea lions, and even dairy cattle suggest the virus is adapting. Mammalian infections usually occur after consuming infected birds or through close contact. Ongoing mutations could increase zoonotic risk.

Can humans get bird flu from eating eggs or poultry?

No, if properly cooked. The virus is destroyed at high temperatures. Always cook poultry to 165°F and eggs until yolks are firm. Avoid raw or undercooked products from outbreak areas.

Is bird flu spreading faster now than before?

Yes. Since 2020, the H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b has caused the largest and most widespread avian epizootic ever recorded, affecting over 100 countries and tens of millions of birds.

What should I do if I find a dead bird?

Do not touch it. Contact your local wildlife agency or health department. They will advise whether testing is needed and how to safely report it.

Are backyard chickens at high risk?

They can be, especially if allowed to roam freely or share spaces with wild birds. Use enclosed runs, clean feeders regularly, and monitor for signs of illness like lethargy, swelling, or sudden death.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4