The dodo bird went extinct primarily due to human activity following its discovery on the island of Mauritius in the late 16th century. How did the dodo birds go extinct? The answer lies in a combination of habitat destruction, introduced species, and direct hunting by sailors and settlers. This flightless bird, unaccustomed to predators, was quickly driven to extinction within less than a century after first contact with humans. Understanding how the dodo became extinct offers critical insight into modern conservation challenges and serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of island ecosystems.

Discovery and Habitat of the Dodo Bird

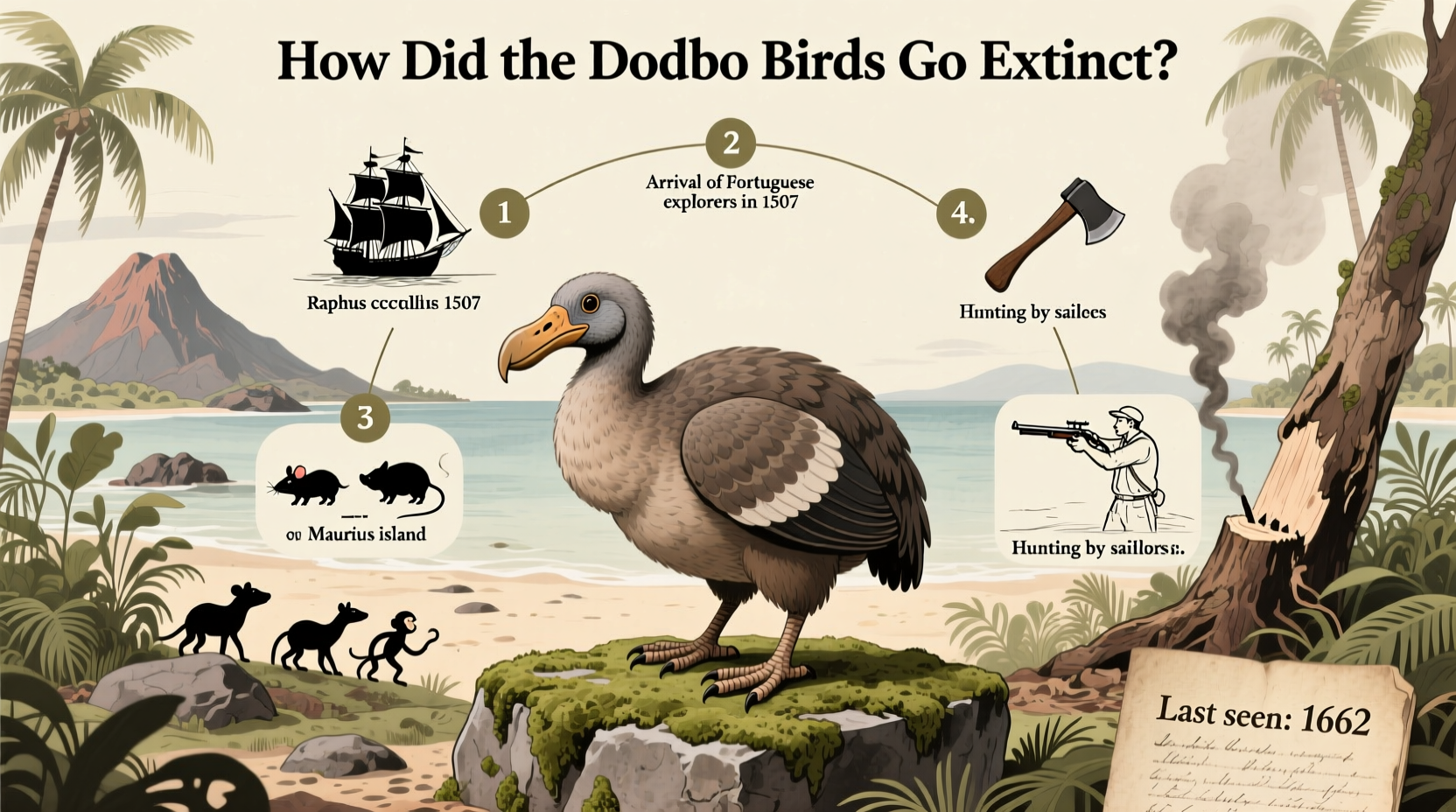

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) was a large, flightless bird endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, located east of Madagascar. It belonged to the Columbidae family, making it a relative of pigeons and doves. First encountered by Dutch sailors in 1598, the dodo had evolved in isolation for millions of years without natural predators, leading to the loss of its ability to fly and a generally docile temperament.

Mauritius provided an ideal environment for the dodo: dense forests with abundant fruit-bearing trees such as tambalacoque, which may have played a role in seed dispersal. With no need to escape predators, energy was not allocated to maintaining strong flight muscles. Instead, the dodo grew to a size of about one meter tall and weighed between 10 to 18 kilograms, making it one of the largest members of its family.

This evolutionary path made the dodo uniquely vulnerable when humans arrived. Unlike mainland species that had co-evolved with predators or human pressures, the dodo had no behavioral or physical defenses against invasive threats.

Timeline of Human Contact and Decline

The extinction timeline of the dodo is relatively short compared to other species. After its discovery in 1598, the bird was frequently encountered by sailors who used Mauritius as a stopover during long sea voyages. These seafarers found the dodo easy to catch and hunted them for food, although reports suggest the meat was tough and unpalatable.

By the early 17th century, permanent settlements were established on the island, accelerating environmental disruption. Historical records indicate that the last widely accepted sighting of a live dodo occurred in 1662, though some estimates place extinction as early as the 1680s. There are no confirmed sightings after 1681, meaning the species likely disappeared less than 100 years after initial human contact.

This rapid decline underscores how quickly human actions can destabilize even stable ecosystems—especially on isolated islands where biodiversity evolves under unique conditions.

Primary Causes of Extinction

While hunting contributed to the dodo’s demise, it was not the sole factor. A confluence of interrelated causes led to its extinction:

- Habitat Destruction: As settlers cleared forests for agriculture and construction, the dodo lost access to nesting sites and food sources.

- Introduced Species: Animals brought by humans—including rats, pigs, dogs, and monkeys—preyed on dodo eggs and competed for food. Rats, in particular, thrived in the new environment and devastated ground-nesting bird populations.

- Lack of Predatory Defense: Having evolved without predators, the dodo showed no fear of humans or animals, making it an easy target.

- Disease: Though less documented, it's possible that pathogens introduced by domestic animals also played a role in weakening the population.

These factors created what ecologists call an 'extinction vortex'—a downward spiral from which recovery becomes impossible once a threshold is crossed.

Myths and Misconceptions About the Dodo

Over time, the dodo has become a symbol of stupidity and laziness, often portrayed in cartoons as slow, clumsy, and foolish. However, this image is a myth rooted more in human bias than biological reality. In truth, the dodo was well-adapted to its environment. Its brain-to-body ratio was comparable to other pigeons, indicating average intelligence for its lineage.

Another common misconception is that the dodo went extinct solely because it was 'too dumb to survive.' In fact, many similarly naive island species have survived longer when human impact was minimal or managed. The real issue wasn't the bird’s behavior—it was the sudden introduction of multiple stressors with no time for adaptation.

Additionally, some believe the dodo was already dying out before humans arrived. But paleontological evidence shows stable populations prior to 1598, with fossils found across various sediment layers indicating longevity and resilience over millennia.

Scientific Rediscovery and Cultural Legacy

For much of the 18th and 19th centuries, the dodo was thought to be mythical. Without complete specimens, scientists debated its existence until subfossil remains were uncovered in swamp deposits on Mauritius in the 1860s. These discoveries confirmed the bird’s anatomy and evolutionary history.

In recent decades, advances in DNA analysis have allowed researchers to sequence parts of the dodo genome, revealing close genetic ties to the Nicobar pigeon. This research helps reconstruct the bird’s evolutionary journey and informs conservation efforts for endangered island species today.

Culturally, the dodo endures as a powerful emblem of extinction. It appears in literature, most famously in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where it represents eccentricity rather than obsolescence. Today, the dodo is the national bird of Mauritius and features on coins and logos, serving both as a source of pride and a reminder of ecological responsibility.

Lessons for Modern Conservation

The story of how the dodo birds went extinct provides vital lessons for contemporary wildlife protection. Island species remain disproportionately at risk due to limited ranges and high specialization. Examples include the kakapo in New Zealand and the Galápagos tortoise, both of which face similar threats from invasive species and habitat fragmentation.

Modern conservation strategies now emphasize biosecurity measures—such as eradicating invasive mammals, restoring native vegetation, and captive breeding programs—to prevent repeating the mistakes of the past. The dodo’s fate illustrates why proactive intervention is essential before populations reach critically low levels.

Moreover, public awareness campaigns use the dodo as an educational tool. By understanding the complex web of causes behind its extinction—not just hunting, but ecosystem-wide disruption—people gain a more nuanced view of biodiversity loss.

Can the Dodo Be Brought Back?

With advancements in genetic technology, there is growing discussion around de-extinction—the idea of reviving extinct species using ancient DNA. Scientists have mapped significant portions of the dodo genome, raising questions about whether it could be resurrected through cloning or gene editing techniques like CRISPR.

However, major ethical and practical hurdles remain. Even if a genetically similar organism were created, it would lack the original ecological context—its habitat has changed dramatically since the 17th century. Reintroduction would require rebuilding entire ecosystems, controlling invasive species, and ensuring long-term sustainability.

Some experts argue that resources should instead focus on preventing current species from going extinct. While de-extinction captures public imagination, preserving existing biodiversity offers more immediate and impactful returns.

Observing Flightless Birds Today: A Guide for Bird Enthusiasts

Though the dodo is gone, numerous flightless birds still exist and offer opportunities for observation and study. These include:

- Kiwi (New Zealand): Nocturnal and shy, best seen on guided eco-tours in protected reserves.

- Penguin (Southern Hemisphere): Various species inhabit coastal regions; popular viewing spots include Patagonia and the Falkland Islands.

- Takahe (New Zealand): Once thought extinct, now conserved through intensive management programs.

- Cassowary (Australia, New Guinea): Dangerous if provoked, but observable in rainforest sanctuaries.

When observing flightless birds, maintain a safe distance, avoid feeding them, and follow local guidelines to minimize disturbance. Many of these species are endangered and protected by law.

| Bird Species | Location | Conservation Status | Best Viewing Season |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kiwi | New Zealand | Vulnerable | Year-round (nocturnal) |

| Emperor Penguin | Antarctica | Near Threatened | April–September |

| Takahe | New Zealand | Endangered | Spring–Summer |

| Southern Cassowary | Queensland, Australia | Vulnerable | Year-round |

Frequently Asked Questions

When did the dodo bird go extinct?

The dodo bird is believed to have gone extinct by the late 17th century, with the last confirmed sighting occurring around 1662. Most scientists agree the species was gone by 1681.

Why couldn’t the dodo fly?

The dodo evolved in the absence of predators on Mauritius, so flight became unnecessary. Over generations, natural selection favored larger body size and reduced wing development, resulting in a flightless bird adapted to ground living.

Did humans directly cause the dodo’s extinction?

Yes, human activities were the primary driver. Hunting, habitat destruction, and the introduction of invasive species like rats and pigs collectively caused the dodo’s rapid extinction.

Is the dodo related to dinosaurs?

No, the dodo is not a dinosaur, but birds—including the dodo—are considered modern descendants of theropod dinosaurs. So while the dodo itself lived recently (Holocene epoch), its evolutionary lineage traces back to prehistoric reptiles.

Can we see a real dodo today?

No living dodos exist. Only bones, fragments, and historical illustrations remain. The most complete specimens are housed in museums, such as the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, which preserves a dried head and foot.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4