If you're wondering how to tell if your chickens have bird flu, the most reliable method is observing sudden and severe symptoms such as a rapid drop in egg production, swelling of the head and neck, nasal discharge, difficulty breathing, diarrhea, and sudden death. A key indicator that may help answer 'how do I know if my chickens have bird flu' is the combination of high mortality rates within 48 hours and neurological signs like twisted necks or lack of coordination. Since avian influenza (AI) spreads quickly and can be fatal, recognizing these early warning signs—especially during peak outbreak seasons—is essential for backyard flock owners and commercial farmers alike.

Understanding Avian Influenza: What It Is and How It Spreads

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, is a highly contagious viral infection caused by influenza A viruses that primarily affect birds. These viruses are naturally found in wild aquatic birds like ducks and geese, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms. However, when transmitted to domestic poultry—including chickens—the results can be devastating. The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds, contaminated feces, respiratory secretions, equipment, clothing, and even dust particles carrying the virus.

There are two main types of avian influenza: low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) and high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). LPAI typically causes mild illness in birds and may go unnoticed, while HPAI spreads rapidly and leads to severe disease with high mortality rates—sometimes killing an entire flock within days. Among the most concerning strains today is H5N1, which has been responsible for widespread outbreaks across North America, Europe, and Asia since 2022, affecting both commercial farms and small backyard flocks.

Early Warning Signs of Bird Flu in Chickens

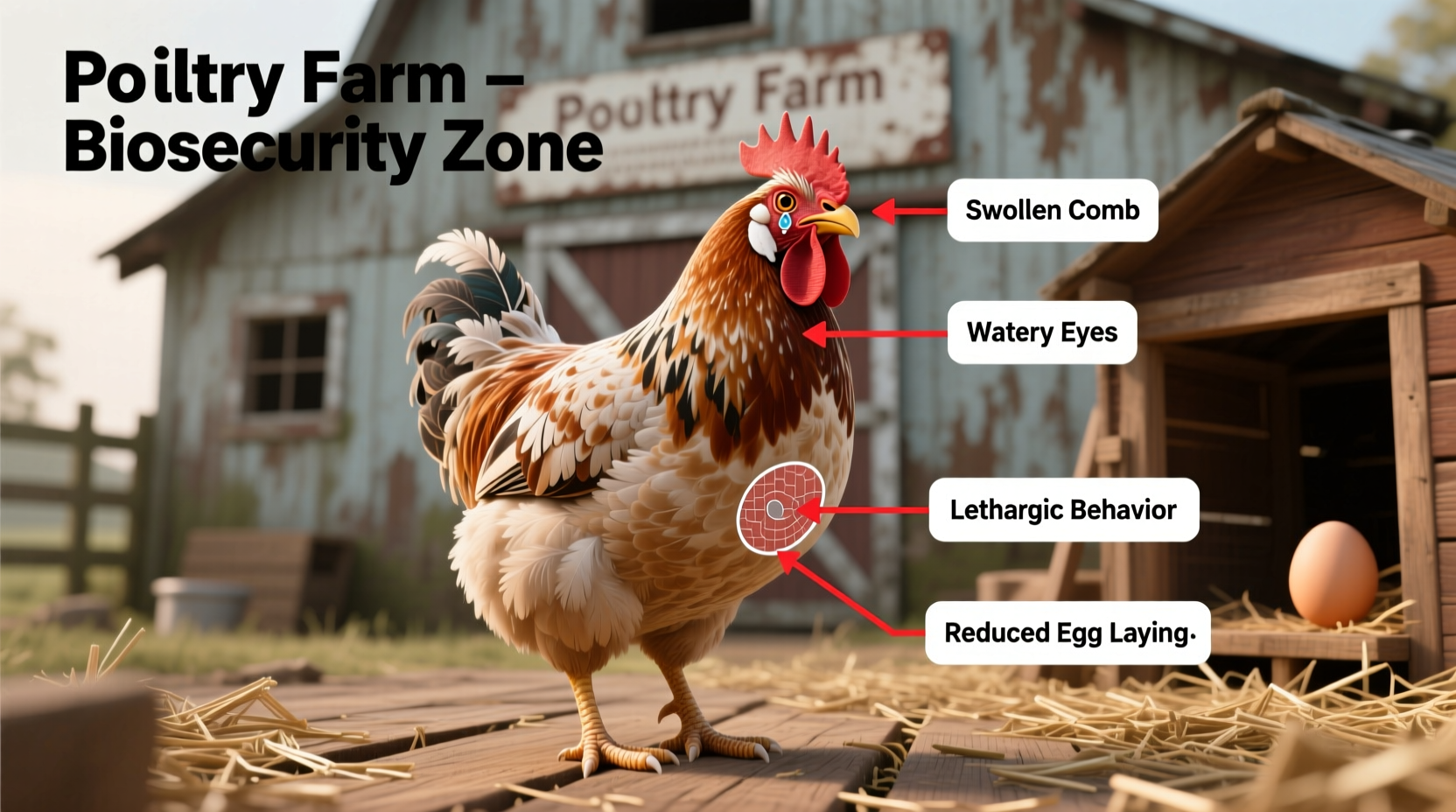

Recognizing the first signs of bird flu in your chickens is critical to preventing further spread. While some symptoms resemble common poultry illnesses, certain patterns point specifically to avian influenza:

- Sudden death without prior symptoms

- Marked decrease or complete halt in egg laying

- Purplish discoloration of wattles, combs, and legs due to poor circulation

- Swelling around the eyes, neck, and head

- Nasal discharge and coughing

- Greenish or watery diarrhea

- Decreased appetite and activity levels

- Neurological issues such as tremors, twisted necks (torticollis), or inability to stand

It's important to note that not all infected birds will show every symptom, but a cluster of these signs—especially sudden deaths combined with respiratory distress—is a red flag. If multiple birds die within 24–48 hours and exhibit any of the above conditions, it’s crucial to act immediately.

Differentiating Bird Flu from Other Poultry Diseases

Several diseases mimic bird flu symptoms, making accurate diagnosis challenging without laboratory testing. For example, Newcastle disease also causes respiratory distress, nervous system disorders, and high mortality. Infectious bronchitis affects the respiratory tract and reduces egg production, similar to mild forms of bird flu. Fowl cholera can lead to sudden death and swollen joints.

The key difference lies in the speed and severity of onset. High pathogenic avian influenza tends to kill large numbers of birds extremely fast—often over 90% mortality in unvaccinated flocks within just a few days. Additionally, external hemorrhaging under the skin, particularly on the legs and around the vent, is more characteristic of HPAI than other diseases.

Because visual inspection alone cannot confirm bird flu, suspected cases must be reported to veterinary authorities for lab analysis. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests performed on swabs from the cloaca or trachea are the gold standard for detection.

What to Do If You Suspect Bird Flu in Your Flock

If you observe symptoms consistent with avian influenza in your chickens, immediate action is required:

- Isolate the flock: Prevent contact between sick birds and healthy ones. Restrict human and animal movement in and out of the coop.

- Avoid handling birds unnecessarily: Wear gloves, masks, and disposable coveralls when near them to reduce transmission risk.

- Contact your veterinarian or local agricultural department: In the U.S., report suspicions to the USDA at 1-866-536-7593 or use the online reporting form. Timely reporting helps contain outbreaks and may qualify you for indemnity payments if depopulation is ordered.

- Do not move birds, eggs, manure, or equipment: Movement restrictions are enforced during confirmed outbreaks to prevent regional spread.

- Disinfect thoroughly: Use approved disinfectants like bleach solutions (1 part bleach to 9 parts water) or commercial products effective against enveloped viruses after cleaning organic material.

Never attempt to treat bird flu with antibiotics, as they only work against bacterial infections and have no effect on viruses.

Prevention Strategies for Backyard Chicken Owners

Preventing bird flu starts with biosecurity—the practice of minimizing exposure to infectious agents. Even small flocks are vulnerable, especially during migration seasons when wild birds pass through local areas.

Effective biosecurity measures include:

- Keeping chickens indoors during known outbreak periods or when migratory birds are present

- Securing coops with netting or enclosures to prevent contact with wild birds

- Cleaning and disinfecting footwear, tools, and vehicles before entering chicken areas

- Avoiding visits to other poultry farms or markets unless absolutely necessary—and changing clothes afterward

- Providing clean feed and water sources protected from contamination

- Quarantining new birds for at least 30 days before introducing them to your existing flock

In regions where HPAI is active, some states mandate temporary indoor confinement orders. Stay informed by checking updates from the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) or your state’s Department of Agriculture website.

Testing and Confirmation: How Veterinarians Diagnose Bird Flu

Only official laboratories can confirm avian influenza. When suspicion arises, trained personnel collect samples using cloacal and oropharyngeal swabs. These are sent to designated National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) facilities in the U.S. for PCR testing.

Rapid antigen tests exist but are less reliable and should not replace confirmatory diagnostics. False negatives can occur if sampling is done too early or improperly. Therefore, even if initial results are negative but clinical signs persist, retesting may be necessary.

In the event of a positive result, regulatory agencies implement control zones, conduct surveillance in surrounding areas, and may require depopulation of affected and exposed flocks to stop the virus from spreading.

Economic and Emotional Impact on Small-Scale Farmers

For backyard chicken keepers, losing a beloved flock to bird flu can be emotionally devastating. Many people raise chickens not just for eggs but as pets or educational projects for children. The sudden loss of birds due to mandatory culling—even if asymptomatic—can feel traumatic.

Commercially, outbreaks lead to trade restrictions, market closures, and financial losses. Although the USDA offers compensation for depopulated birds, the process can be slow and does not cover lost income or emotional toll. This underscores the importance of proactive prevention and early detection.

Public Health Concerns: Can Humans Get Bird Flu?

While rare, certain strains of avian influenza—particularly H5N1 and H7N9—can infect humans, usually through close, prolonged contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. Most human cases have occurred in Asia among individuals who lived with poultry in unsanitary conditions.

To date, there is no evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission. Still, public health officials monitor outbreaks closely. If you handle sick or dead birds, always wear personal protective equipment (PPE), including N95 masks, eye protection, and waterproof gloves.

The CDC advises avoiding contact with wild birds and never bringing dead or ill birds into your home. If you develop fever, cough, sore throat, or difficulty breathing within 10 days of bird exposure, seek medical attention and inform your doctor about the contact history.

Regional Differences in Bird Flu Risk and Response

Bird flu risk varies significantly by region and season. In temperate climates, outbreaks often coincide with spring and fall bird migrations. States like Iowa, Minnesota, and California have experienced major outbreaks due to their proximity to migratory flyways and dense poultry operations.

Urban versus rural settings also influence risk. Rural farms may face higher exposure from wild waterfowl accessing ponds or fields, while urban coops benefit from fewer natural reservoirs—but remain vulnerable if owners transport birds to shows or swap meets.

International differences matter too. Countries with routine vaccination programs (e.g., China, Egypt) manage the disease differently than those relying solely on surveillance and culling (e.g., U.S., EU). Always check current status maps from sources like the OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) or FAO for global context.

| Symptom | Bird Flu (HPAI) | Newcastle Disease | Infectious Bronchitis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality Rate | Very high (>90%) | High (up to 100%) | Low to moderate |

| Egg Drop | Sudden, near-total cessation | Significant reduction | Moderate reduction, misshapen eggs |

| Respiratory Signs | Present (coughing, gasping) | Severe (gasping, sneezing) | Prominent (rattling, wheezing) |

| Neurological Symptoms | Common (twisted neck, paralysis) | Very common (circling, tremors) | Rare |

| Swelling of Head/Comb | Frequent | Occasional | No |

Frequently Asked Questions About Detecting Bird Flu in Chickens

How soon after exposure do chickens show signs of bird flu?

Chickens can begin showing symptoms within 2 to 7 days after exposure, though in high-pathogenicity strains, death may occur before obvious signs appear.

Can vaccinated chickens still get bird flu?

Vaccination is not widely used in the U.S. due to trade implications and inability to distinguish vaccinated from infected birds. Where used, vaccines reduce disease severity but don’t guarantee full protection.

Is there a home test for bird flu in chickens?

No reliable home test exists. Rapid field kits are available to veterinarians but require confirmation via lab PCR testing.

Should I kill my chickens if I suspect bird flu?

Do not slaughter or consume birds from a suspected infected flock. Human consumption poses potential risks, and carcasses must be safely disposed of per regulatory guidelines.

Where can I find real-time bird flu outbreak data?

Check the USDA APHIS website (https://www.aphis.usda.gov) for updated maps of confirmed cases in U.S. commercial and backyard flocks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4