Birds breathe using a highly specialized and efficient respiratory system that allows for continuous airflow through their lungs, enabling them to meet the high oxygen demands of flight. Unlike mammals, birds have rigid lungs connected to a network of air sacs distributed throughout their body, which facilitate a one-way flow of airâthis is known as cross-current gas exchange. This unique mechanism ensures that fresh oxygen-rich air passes through the lungs during both inhalation and exhalation, maximizing oxygen absorption. Understanding how do birds breathe reveals not only their remarkable evolutionary adaptations but also explains their ability to thrive in extreme environmentsâfrom high-altitude migrations to rapid aerial maneuvers.

The Anatomy of Avian Respiration

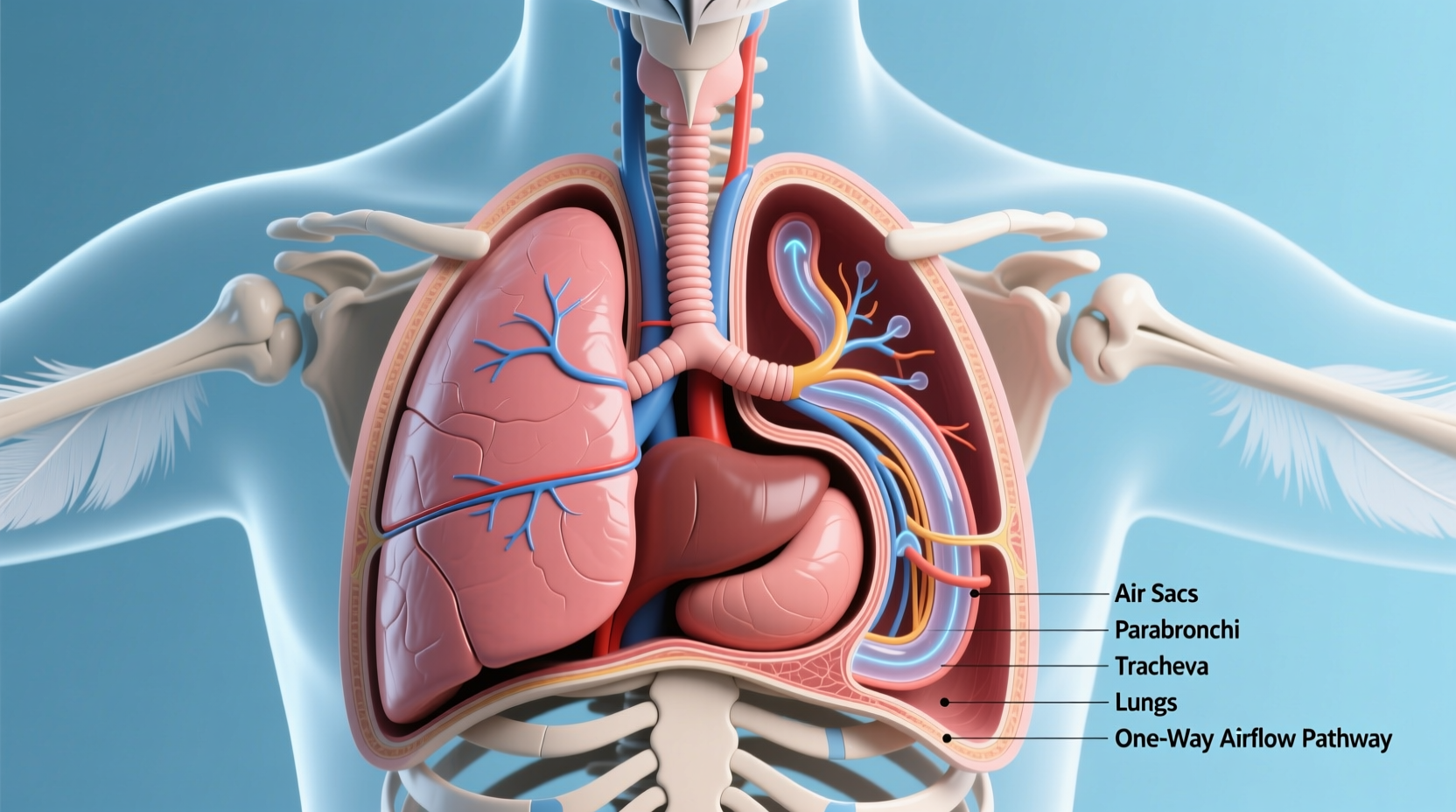

The bird respiratory system differs fundamentally from that of mammals. In humans and other mammals, air moves in and out of the same pathway in a tidal fashionâlike waves going back and forth. Birds, however, use a system based on unidirectional airflow, made possible by nine interconnected air sacs and rigid, non-expanding lungs.

Air enters through the nostrils (nares) or mouth and travels down the trachea, which splits into two primary bronchi leading to the lungs. From there, air flows into posterior air sacs during the first inhalation. On exhalation, this stored air moves from the posterior sacs into the lungs, where gas exchange occurs in tiny tubules called parabronchi. A second inhalation pushes the now-oxygen-depleted air into anterior air sacs, and finally, it's expelled during the next exhalation.

This two-cycle process means that every breath delivers fresh air to the lungs twiceâonce on inhalation and once on exhalationâmaking avian respiration significantly more efficient than mammalian systems. This efficiency is essential for sustaining the high metabolic rates required for powered flight.

Key Structures Involved in Bird Breathing

To fully grasp how do birds breathe, itâs important to understand the main anatomical components:

- Lungs: Small, dense, and fixed in place; they donât expand or contract like mammalian lungs.

- Air Sacs: Thin-walled, balloon-like structures that act as bellows to move air through the system. There are typically nine: four paired (cervical, clavicular, anterior thoracic, posterior thoracic) and one unpaired (abdominal).

- Parabronchi: Tiny channels within the lungs where oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged across blood capillaries.

- Syrinx: Located at the base of the trachea, this vocal organ doesn't play a direct role in breathing but illustrates the complexity of airflow control in birds.

These structures work together seamlessly to maintain constant oxygen deliveryâeven during strenuous activity such as hovering, diving, or flying at altitudes exceeding 20,000 feet, where oxygen levels are extremely low.

Why Birds Need Such an Efficient System

Flight is one of the most energy-intensive forms of locomotion. To sustain it, birds require a tremendous amount of oxygen to fuel aerobic metabolism. Their body temperatures often exceed 104°F (40°C), and heart rates can reach over 1,000 beats per minute in small species like hummingbirds. These physiological demands necessitate a respiratory system far more advanced than that of most terrestrial animals.

For example, bar-headed geese migrate over the Himalayas, flying above Mount Everestâs peak altitude. At those heights, atmospheric pressure is less than one-third of sea level, yet these birds maintain adequate oxygen supply thanks to their superior lung structure, increased hemoglobin affinity for oxygen, and enhanced capillary density in muscles.

Moreover, because birds lack a diaphragm, they rely on skeletal movementsâespecially those of the ribs and sternumâto pump air through their air sacs. This integration between respiration and locomotion further highlights the evolutionary refinement of avian breathing.

Comparing Bird and Mammal Respiratory Systems

Understanding how do birds breathe becomes clearer when contrasted with mammalian respiration:

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Airflow Pattern | Unidirectional (one-way) | Tidal (in and out same path) |

| Lung Movement | Rigid, non-expanding | Elastic, expand/contract |

| Gas Exchange Timing | Dual-phase (during inhale & exhale) | Single-phase (only during inhale) |

| Oxygen Extraction Efficiency | High (~30% extraction rate) | Moderate (~25% extraction rate) |

| Presence of Air Sacs | Yes (9 major sacs) | No |

| Respiratory Control | Coupled with wingbeat/posture | Diaphragm-driven |

This comparison underscores why birds can perform feats impossible for similarly sized mammals. The absence of alveoli and presence of parabronchial flow-through design gives birds a competitive edge in oxygen utilization, especially under hypoxic conditions.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Breathing

Despite growing scientific understanding, several myths persist about avian respiration:

- Myth: Birds breathe like humans, just faster.

Reality: The entire mechanism is structurally differentâbirds donât inflate their lungs; instead, air sacs manage airflow while lungs remain static. - Myth: Birds can hold their breath underwater like marine mammals.

Reality: While some diving birds (e.g., penguins) can reduce oxygen consumption, they cannot extract oxygen from water and must surface to breathe. - Myth: All birds have the same respiratory capacity.

Reality: Respiratory efficiency varies widely among species depending on lifestyle. Hummingbirds and migratory shorebirds have the most developed systems relative to size.

Observing Bird Breathing: Tips for Birdwatchers

While you canât see internal air sacs, observant birdwatchers can detect signs of respiratory function:

- Look for subtle chest movements: Especially in resting birds, slight expansions near the keel bone may indicate air sac pumping.

- Watch behavior after flight: After intense activity, birds may pant or gular flutter (vibrate throat membranes) to cool down without compromising oxygen intake. \li>Note posture changes: Some birds adjust body position to optimize airflowâsuch as puffing up feathers or tilting the head during vocalization.

- Listen closely: Sounds produced at the syrinx (like song or calls) reflect precise control over airflow, indirectly revealing respiratory health.

For researchers and enthusiasts, monitoring breathing patterns can help assess stress levels, fitness, or illness. Rapid, labored breathing in captive or injured birds may signal respiratory infectionâa common issue in wild populations exposed to pollutants or pathogens.

Environmental and Health Impacts on Avian Respiration

Birds are particularly vulnerable to airborne toxins due to their high ventilation rates and sensitive respiratory tissues. Pollutants such as cigarette smoke, cleaning chemicals, and agricultural pesticides can cause severe damage to delicate lung structures.

In urban areas, air pollution has been linked to reduced lung function and altered migration timing in species like house sparrows and starlings. Similarly, climate change affects oxygen availability at high elevations, potentially disrupting traditional flyways used by geese, swans, and raptors.

Veterinarians treating pet birds (e.g., parrots, canaries) emphasize clean environments and proper ventilation. Signs of respiratory distress include tail bobbing, wheezing, nasal discharge, and open-mouth breathingâall warranting immediate attention.

Evolutionary Origins of the Avian Respiratory System

The origins of the modern bird respiratory system trace back to theropod dinosaursâthe ancestors of todayâs birds. Fossil evidence suggests that some non-avian dinosaurs, including Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor, had similar air sac systems embedded in their bones (pneumatized vertebrae), indicating early development of unidirectional airflow.

This adaptation likely evolved initially for thermoregulation and weight reduction rather than flight. Over millions of years, natural selection refined this system to support endothermy (warm-bloodedness) and eventually powered flight in early birds like Archaeopteryx.

Thus, studying how do birds breathe offers insights not only into modern biology but also into deep evolutionary history, connecting living species to their prehistoric relatives.

Practical Applications and Scientific Research

Understanding avian respiration has real-world applications beyond ornithology:

- Aerospace Engineering: Engineers study bird airflow dynamics to improve drone design and aircraft ventilation systems.

- Medical Science: Researchers explore cross-current exchange models to develop better artificial lungs or oxygenators for human patients.

- Conservation Biology: Monitoring respiratory performance helps evaluate habitat quality and species resilience in changing climates.

Additionally, scientists use respirometryâthe measurement of oxygen consumptionâto study metabolic rates in birds under various conditions, contributing to broader ecological and physiological knowledge.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Do birds breathe through their mouth or nose?

Birds primarily breathe through their nostrils (nares), located at the base of the beak, though they can also take in air through the mouth if needed, especially during heavy activity or heat dissipation.

Can birds breathe while flying?

Yes, birds are specially adapted to breathe efficiently during flight. Their air sac system ensures continuous oxygen delivery regardless of wingbeat cycle, allowing sustained aerobic activity.

How fast do birds breathe?

Breathing rates vary by species and activity level. A resting pigeon may breathe 25â40 times per minute, while a flying hummingbird can exceed 250 breaths per minute.

Do baby birds breathe differently?

Nestlings have the same basic respiratory anatomy but may have less developed air sacs. They rely on parents for warmth and protection, reducing metabolic strain during early development.

Can birds suffocate in enclosed spaces?

Yes, birds are highly sensitive to poor air quality and can quickly succumb to low oxygen or toxic fumes in poorly ventilated enclosures. Always ensure cages and transport containers have ample airflow.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4