People catch bird flu, also known as avian influenza, primarily through direct contact with infected birds or their secretions, including saliva, nasal discharge, and feces. The most common way humans contract the virus is by handling live or dead poultry that are infected, especially in rural or agricultural settings where backyard flocks are present. A natural longtail keyword variant such as 'how do people catch bird flu from chickens' reflects a frequent user concernâparticularly among small-scale farmers, bird handlers, and those visiting live bird markets. While human-to-human transmission remains rare, exposure to contaminated environments, such as unclean coops or surfaces touched by infected birds, increases risk. Public health agencies emphasize that proper hygiene, protective gear, and avoiding sick or dead birds significantly reduce infection chances.

Understanding Bird Flu: A Biological Overview

Bird flu is caused by influenza A viruses, which naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds like ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent carriers. However, when the virus spreads to domesticated birdsâsuch as chickens, turkeys, and quailsâit can cause severe illness and high mortality rates. There are numerous subtypes of avian influenza, classified by surface proteins hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), with H5N1 and H7N9 being particularly notable for their zoonotic potentialâthe ability to jump from birds to humans.

The virus thrives in cool, moist environments and can survive for days on surfaces, in water, or in manure. This environmental persistence plays a critical role in indirect transmission. For example, stepping into soil contaminated with bird droppings and then touching oneâs face could lead to infection, though this route is less common than direct animal contact.

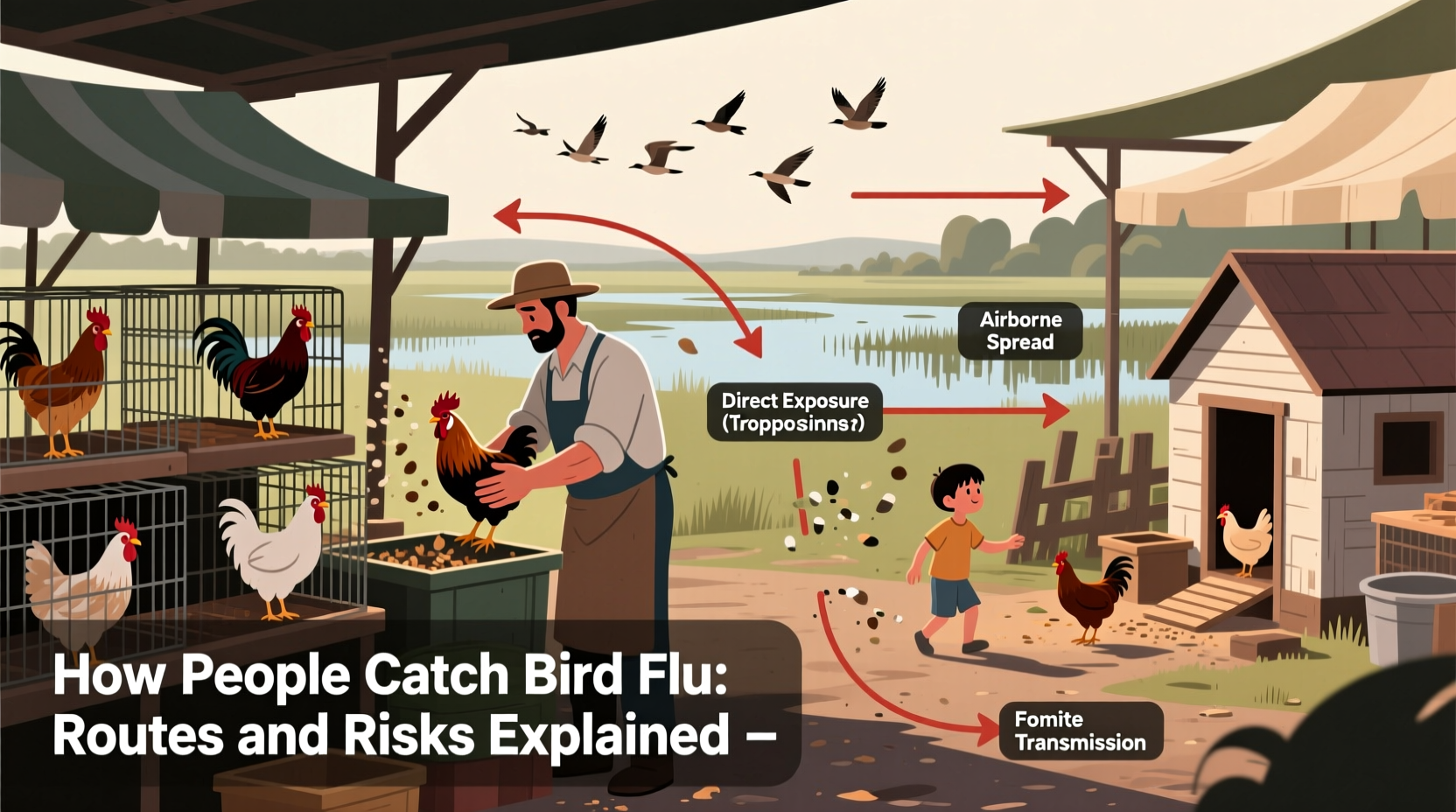

Primary Routes of Human Infection

There are several well-documented ways people catch bird flu. Understanding these pathways helps individuals take preventive measures, especially in high-risk regions or occupations.

- Direct Contact with Infected Birds: Farmers, veterinarians, slaughterhouse workers, and others who handle live or dead infected poultry are at highest risk. Plucking feathers, cleaning cages, or butchering birds without gloves or masks increases exposure.

- Inhalation of Virus Particles: In enclosed spaces like barns or live bird markets, airborne particles containing the virus can be inhaled. This aerosol transmission has been observed during outbreaks, especially when ventilation is poor.

- Contact with Contaminated Surfaces: The virus can linger on equipment, clothing, feed containers, and vehicles used around infected flocks. Touching these items and then touching the mouth, nose, or eyes may result in infection.

- Consumption of Undercooked Poultry Products: While thoroughly cooked meat and eggs pose no risk, consuming raw or undercooked products from infected birdsâsuch as blood puddings or soft-boiled eggsâhas been linked to isolated cases, particularly in parts of Asia.

It's important to note that eating properly handled and cooked poultry does not transmit bird flu. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and World Health Organization (WHO) confirm that cooking poultry to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) kills the virus.

Geographic and Seasonal Patterns of Bird Flu Outbreaks

Bird flu outbreaks tend to follow seasonal migration patterns of wild birds. In temperate zones, peak activity often occurs during fall and winter months when migratory birds travel south, potentially introducing the virus to new areas. Regions with dense poultry populationsâsuch as Southeast Asia, parts of Africa, and Eastern Europeâare more prone to spillover events.

For instance, countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, and Egypt have reported multiple human cases due to close human-bird interactions in backyard farming systems. In contrast, North America and Western Europe see fewer human infections, largely because of stricter biosecurity measures and limited public access to affected farms.

Climate change and habitat disruption may influence future patterns. Warmer temperatures and shifting migration routes could expand the geographic range of both wild carriers and outbreak risks.

High-Risk Groups and Occupational Exposure

Certain populations face greater exposure to avian influenza:

- Poultry Workers: Employees at commercial farms, hatcheries, and slaughterhouses must follow strict safety protocols, including wearing personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Veterinarians and Animal Health Inspectors: Regular interaction with sick birds requires training in disease recognition and containment procedures. \li>Backyard Flock Owners: Hobbyists raising chickens for eggs or pets may lack awareness of biosecurity practices, increasing vulnerability during regional outbreaks.

- Travelers to Affected Areas: Visitors to regions experiencing active bird flu outbreaks should avoid live bird markets and refrain from touching unfamiliar birds.

Public health authorities recommend that high-risk individuals receive seasonal flu vaccinesânot because it protects against bird flu directly, but because it reduces the chance of dual infection, which could allow genetic reassortment and create a more transmissible strain.

Misconceptions About Bird Flu Transmission

Several myths persist about how people catch bird flu. Addressing these misconceptions is crucial for accurate risk assessment:

| Misconception | Fact |

|---|---|

| You can easily catch bird flu from eating chicken. | Noâproperly cooked poultry is safe. The virus is destroyed by heat. |

| Bird flu spreads rapidly between people. | Human-to-human transmission is extremely rare and not sustained. |

| All bird species are equally likely to spread the virus. | Ducks and other waterfowl often carry it asymptomatically; chickens show severe signs. |

| Pets like parrots or canaries commonly transmit bird flu. | Companion birds are rarely involved in human infections unless exposed to wild birds. |

Prevention and Safety Measures

Preventing bird flu in humans starts with controlling the virus in bird populations. Key strategies include:

- Biosecurity on Farms: Limiting access to poultry areas, disinfecting footwear and tools, and isolating new birds before introducing them to flocks.

- Surveillance and Reporting: Governments and agricultural departments monitor wild and domestic bird populations for early detection. Prompt reporting of sick or dead birds enables rapid response.

- Personal Protection: Use gloves, masks, and goggles when handling birds. Wash hands thoroughly afterwardâeven if gloves were worn.

- Avoiding High-Risk Environments: Steer clear of live bird markets in countries with ongoing outbreaks. Travel advisories from the CDC or WHO can guide decisions.

- Vaccination of Poultry: In some countries, poultry are vaccinated against specific strains, reducing viral spread.

For backyard flock owners, simple steps like keeping feed covered, preventing wild bird access, and quarantining sick animals can make a significant difference.

Global Response and Public Health Monitoring

International cooperation is essential in managing bird flu threats. Organizations like the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) collaborate to track outbreaks, share data, and support control efforts.

The CDC maintains a watchlist of avian influenza strains with pandemic potential. When human cases occur, contact tracing and antiviral treatment (e.g., oseltamivir) are initiated promptly. Surveillance programs also analyze whether the virus is acquiring mutations that could enhance human infectivity.

In recent years, advances in genomic sequencing have improved early warning systems. Scientists can now identify emerging variants faster, allowing quicker vaccine development if needed.

What to Do If You Suspect Bird Flu Exposure

If youâve had close contact with sick or dead birds and develop symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, or difficulty breathing within 10 days, seek medical attention immediately. Inform your healthcare provider about the exposure so they can test for avian influenza and initiate appropriate isolation and treatment protocols.

Do not wait for symptoms to worsen. Early antiviral treatment improves outcomes. Additionally, avoid contact with others until cleared by a doctor to prevent potential spread.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Ongoing research focuses on developing universal influenza vaccines that could protect against multiple strains, including avian variants. Scientists are also studying the ecology of wild bird migrations to predict hotspots of viral emergence.

Another area of interest is improving rapid diagnostic tools for use in remote or resource-limited areas. Faster identification means quicker containment.

As global demand for poultry grows, balancing food security with disease prevention will remain a challenge. Sustainable farming practices, enhanced surveillance, and public education are key to minimizing future risks.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can you get bird flu from pet birds?

- Itâs very unlikely unless your pet bird has been exposed to infected wild birds. Indoor birds kept away from external sources pose minimal risk.

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

- There is no widely available commercial vaccine, but candidate vaccines exist for certain strains (like H5N1) and are stockpiled for emergency use.

- How long does bird flu last in the environment?

- The virus can survive in cool, damp conditions for up to several weeks, especially in water or manure.

- Are all bird species susceptible to bird flu?

- Most birds can be infected, but waterfowl are primary reservoirs, while gallinaceous birds (chickens, turkeys) suffer higher mortality.

- Has bird flu ever caused a pandemic?

- Not yet. Although some strains have infected humans, none have gained the ability to spread efficiently from person to person.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4