Birds hear through a specialized auditory system that allows them to detect sounds critical for communication, navigation, and survival. Unlike mammals, birds lack external ears, but they possess highly developed inner and middle ear structures capable of processing a wide range of frequencies. A key adaptation in avian hearing is how birds hear environmental cues such as predator calls, mating songs, and flock signals—enabling behaviors essential to their daily lives. This natural ability to interpret complex soundscapes plays a vital role in bird behavior and ecology.

Anatomy of Bird Hearing: How Birds Detect Sound Without External Ears

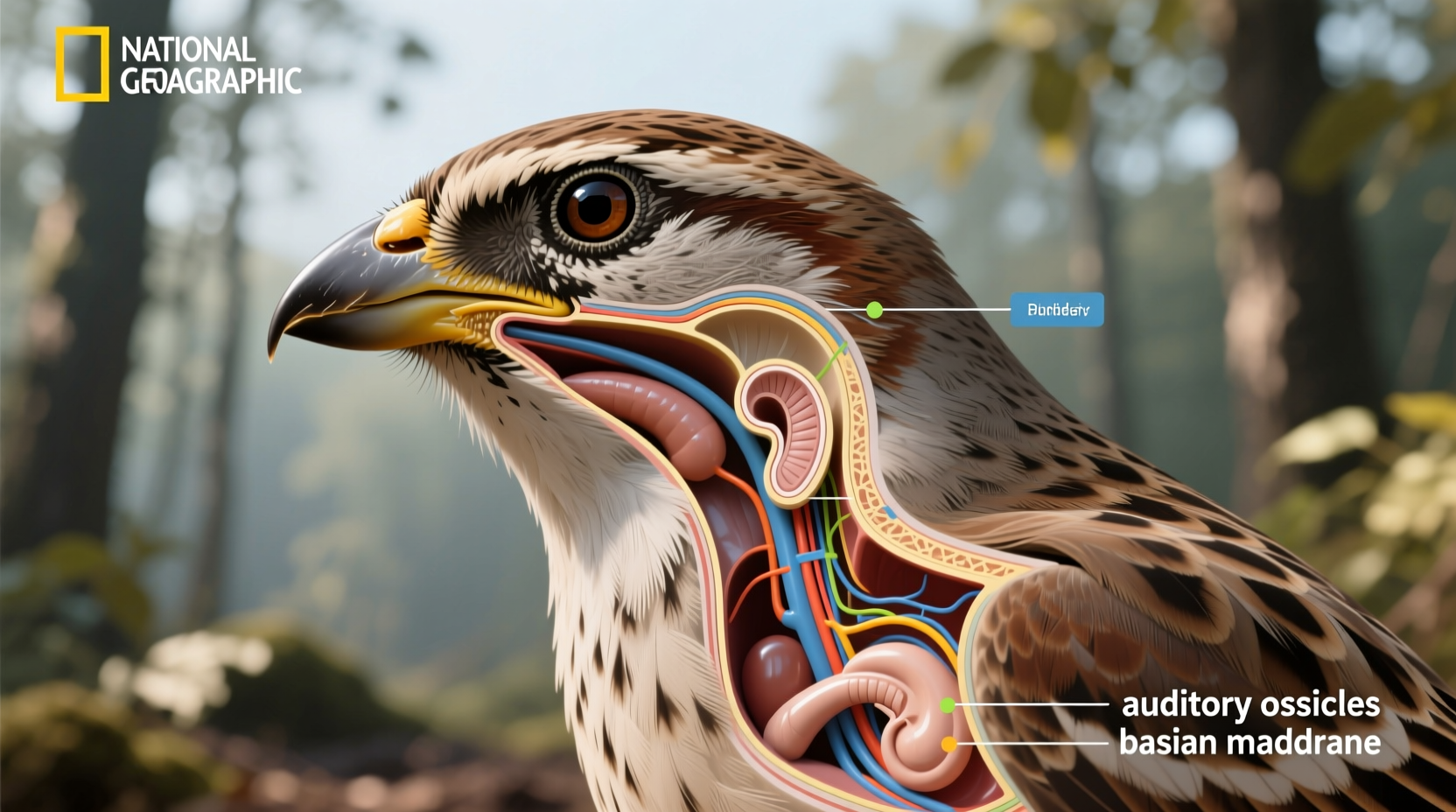

One of the most frequently asked questions in ornithology is how do birds hear without visible ears? The answer lies in their unique anatomical structure. While birds don’t have pinnae (external ear flaps like humans), they have small openings on each side of the head, usually hidden beneath feathers. These openings lead directly to the ear canal and then to the tympanic membrane (eardrum). From there, sound vibrations travel through the middle ear via a single bone called the columella (homologous to the mammalian stapes) into the inner ear.

The inner ear contains the cochlea, which in birds is shorter than in mammals but remarkably efficient. Hair cells within the basilar papilla (the avian equivalent of the organ of Corti) convert mechanical sound waves into neural signals sent to the brain. Despite lacking external structures to funnel sound, many bird species have evolved feather arrangements around the ear region—especially in owls—that act as sound-reflecting funnels, enhancing directional hearing.

Frequency Range and Sensitivity: What Sounds Can Birds Actually Hear?

Birds generally hear within a frequency range of 1,000 to 4,000 Hz, though some species can perceive sounds outside this band. For example, pigeons can detect infrasound below 100 Hz, possibly aiding in long-distance navigation. Songbirds, such as canaries and zebra finches, are sensitive to higher frequencies up to 8,000–10,000 Hz, crucial for interpreting complex vocalizations during courtship.

Unlike humans who peak in sensitivity around 2,000–5,000 Hz, birds’ hearing is finely tuned to biologically relevant sounds. Research shows that many birds cannot hear ultrasonic frequencies (>20,000 Hz) used by bats or rodent repellents, meaning these devices pose no auditory disruption to most wild bird populations. However, parrots and other psittacines demonstrate broader auditory ranges, allowing them to mimic human speech with precision—an ability rooted in both hearing acuity and vocal learning centers in the brain.

Directional Hearing and Sound Localization in Birds

A critical aspect of how birds hear in three-dimensional space involves sound localization—the ability to pinpoint where a noise originates. Most birds use interaural time differences (the slight delay between when a sound reaches one ear versus the other) to determine horizontal position. However, vertical localization presents a greater challenge due to the lack of external ear structures that help mammals filter sound directionally.

Owls represent an evolutionary pinnacle in avian auditory specialization. Species like the barn owl (Tyto alba) have asymmetrical ear placements—one ear opening higher than the other—which allows them to triangulate prey under complete darkness. Their facial disc feathers form a parabolic reflector that channels sound precisely toward the ears. This adaptation enables barn owls to catch mice based solely on rustling noises in grass, even when covered by snow.

In contrast, songbirds rely more on visual cues combined with auditory input, while waterfowl and shorebirds often depend on broad-spectrum hearing to monitor group movements across open habitats. Understanding how different bird species process directional sound helps explain variations in social behavior, predator avoidance, and habitat selection.

The Role of Hearing in Bird Communication and Behavior

Hearing is fundamental to avian communication. Birds produce and interpret a vast array of calls and songs, each serving distinct functions—from territory defense to mate attraction. The syrinx, located at the base of the trachea, generates these sounds, which are then perceived by listeners through their auditory pathways.

Many species exhibit dialects—regional variations in song patterns—indicating learned components in vocalization. Young birds must hear adult tutors during a sensitive developmental period to acquire proper songs. Deafened individuals fail to develop normal vocalizations, underscoring the tight link between hearing and vocal production.

Besides conspecific communication, birds also respond to heterospecific signals. Chickadees, for instance, recognize alarm calls from nuthatches and titmice, using them as early warnings. Similarly, mobbing calls attract multiple species to harass predators, demonstrating cross-species acoustic awareness made possible by shared hearing capabilities.

Noise Pollution and Its Impact on Avian Hearing

Urbanization has introduced unprecedented levels of anthropogenic noise, raising concerns about how birds hear in noisy environments. Traffic, construction, and industrial activity generate low-frequency rumbles that overlap with common bird vocalizations. Studies show that city-dwelling great tits sing at higher pitches to avoid masking by background noise—a phenomenon known as the Lombard effect.

Prolonged exposure to loud sounds can cause temporary or permanent hearing loss in birds, particularly in captive settings like zoos or aviaries near airports. Feather condition, stress hormones, and reproductive success have all been linked to chronic noise exposure. Conservationists now consider acoustic habitat quality when designing protected areas, emphasizing the need to preserve quiet zones for sound-sensitive species like thrushes and nightjars.

For birdwatchers and researchers, minimizing noise during fieldwork improves observation accuracy and reduces disturbance. Using silent clothing, avoiding sudden loud noises, and maintaining distance enhance both data collection and animal welfare.

Comparative Hearing: Birds vs. Mammals

A common misconception is whether birds are mammals. They are not—birds belong to the class Aves, characterized by feathers, beaks, egg-laying, and endothermy, whereas mammals are warm-blooded vertebrates with hair and mammary glands. In terms of hearing, mammals typically have more complex outer and middle ear structures, including movable pinnae that actively focus sound.

Despite structural differences, both groups share similar neural mechanisms for processing sound in the brainstem and auditory cortex (or its avian equivalent, the mesencephalicus lateralis dorsalis). However, birds generally have faster auditory response times, enabling split-second reactions to aerial threats. Additionally, birds regenerate damaged hair cells in the inner ear—a capability lost in adult mammals—offering hope for future biomedical research on hearing restoration.

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| External Ear | Absent (feather-covered openings) | Present (pinnae in most) |

| Middle Ear Bone | Columella (1 bone) | Malleus, incus, stapes (3 bones) |

| Frequency Range | ~100–10,000 Hz (species-dependent) | ~20–20,000 Hz (humans); wider in others |

| Hair Cell Regeneration | Yes | No (in adults) |

| Vocal Learning Link | Strong (songbirds, parrots) | Limited (humans, cetaceans) |

Observing Bird Hearing in the Wild: Tips for Birdwatchers

Understanding how birds hear can improve your birdwatching experience. Since many species are heard before they’re seen, developing 'auditory awareness' enhances detection rates. Here are practical tips:

- Move quietly: Avoid crunching leaves or snapping twigs. Wear soft-soled shoes and move slowly.

- Listen at dawn: Morning hours offer peak bird vocal activity, especially during breeding season.

- Identify call types: Learn distinctions between songs (longer, complex, territorial/mating) and calls (short, alert, contact).

- Use playback sparingly: Playing recorded bird songs can disrupt natural behavior and stress animals. Use only when necessary and follow local ethical guidelines.

- Note silence: Sudden quiet may indicate a predator nearby, such as a hawk or cat.

Investing in a good pair of binoculars and a digital recorder or smartphone app (like Merlin Bird ID) can help match sounds to species. Always respect private property and protected areas when observing birds.

Myths and Misconceptions About Bird Hearing

Several myths persist about avian hearing. One widespread belief is that birds can't hear at all, likely because they lack visible ears. This is false—birds hear well within their ecological needs. Another myth suggests that playing music affects birds negatively. While extremely loud or repetitive artificial sounds may cause stress, moderate ambient noise doesn’t harm most birds.

Some believe that all birds hear ultrasound, making them susceptible to pest control devices. As previously noted, most birds cannot perceive ultrasonic frequencies, so these gadgets have little impact on avian behavior. Finally, the idea that birds lose hearing with age is understudied, but unlike mammals, birds retain regenerative capacity in their auditory systems, potentially preserving function longer.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can birds hear human voices?

- Yes, many birds—especially parrots, crows, and mynas—can hear and distinguish human speech. Some even mimic words due to advanced vocal learning abilities.

- Do birds have a sense of pitch?

- Yes, birds exhibit strong pitch discrimination. Songbirds organize melodies with precise intervals, and experiments show they prefer consonant over dissonant sounds.

- Are birds affected by loud music or fireworks?

- Yes, sudden loud noises can startle birds, disrupt feeding or nesting, and trigger flight responses. Fireworks have been linked to mass bird die-offs due to panic-induced exhaustion.

- How do baby birds learn to recognize their parents' calls?

- Nestlings imprint on parental vocalizations shortly after hatching. This auditory recognition ensures they respond only to correct caregivers, reducing predation risk.

- Can deafness occur in birds?

- Yes, though rare in the wild, deafness can result from infection, trauma, or genetic factors. Captive birds exposed to loud noises are more vulnerable.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4