The drinking bird toy operates through a combination of thermodynamics, evaporation, and pressure differences, making it a fascinating example of how heat energy can produce continuous motion. Often mistaken for a living creature due to its repetitive dipping motion, the drinking bird is actually a simple heat engine that relies on the temperature difference between its head and base to function. This classic science novelty, sometimes referred to as the 'dipping bird' or 'water-drinking bird,' demonstrates principles of phase change, vapor pressure, and capillary action in an engaging, visual way. Understanding how does the drinking bird work reveals not only the clever physics behind its movement but also offers insight into real-world applications of thermal dynamics.

The Science Behind the Drinking Bird's Motion

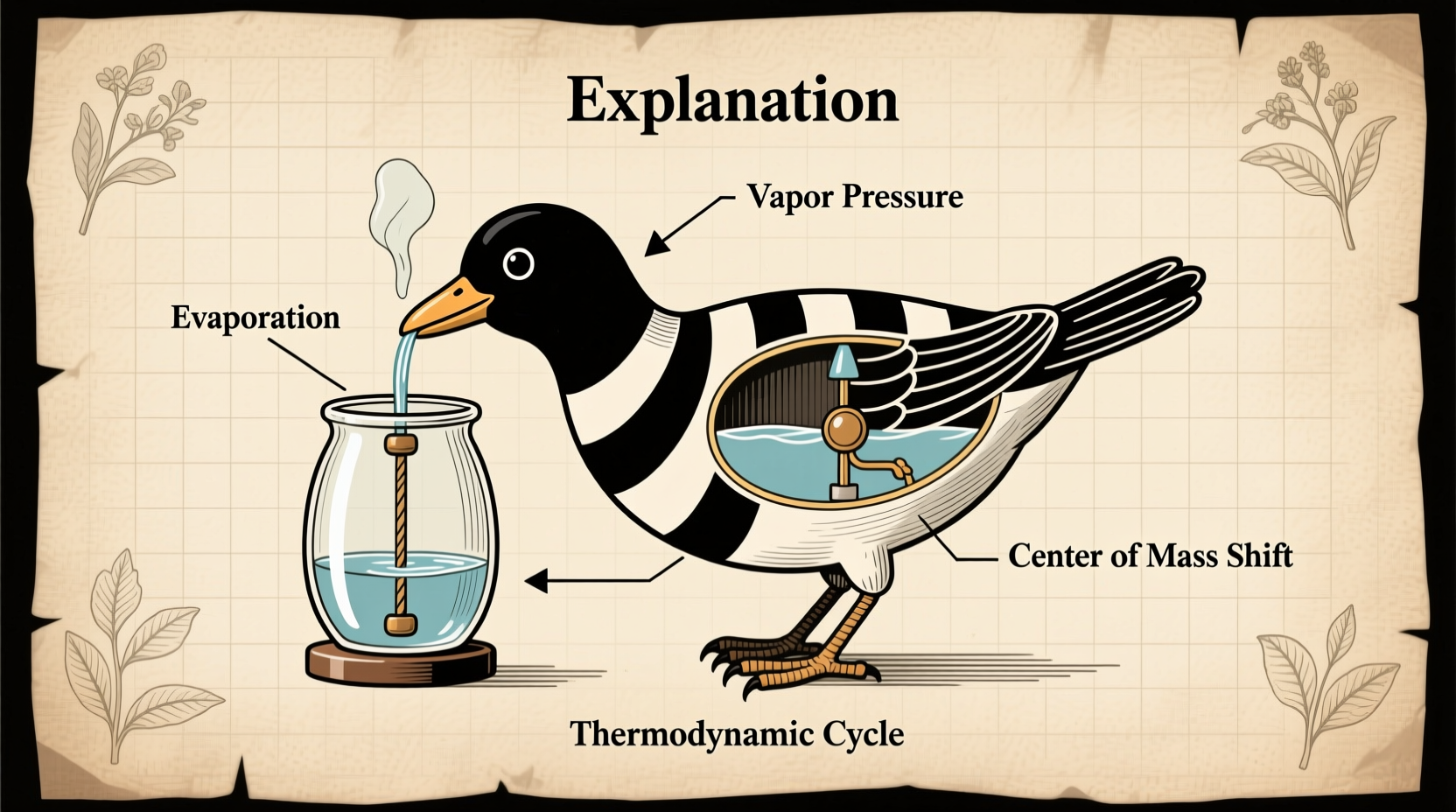

At first glance, the drinking bird appears almost magical—its head dips forward repeatedly, as if sipping water from a glass, then slowly rights itself only to dip again. However, this perpetual motion is driven entirely by physical laws, specifically the principles of evaporation, condensation, and vapor pressure.

The bird is typically made of two glass bulbs connected by a glass tube, forming a sealed system. The lower bulb (the body) contains a volatile liquid—usually methylene chloride—which has a low boiling point and easily evaporates at room temperature. The upper bulb (the head) is coated with felt, which absorbs water when dipped. As the water evaporates from the felt, it cools the head, causing the vapor inside to condense. This creates a pressure difference between the cooler head and the warmer base.

Because pressure drops in the head, liquid is pushed up the central tube from the base toward the head. As more fluid rises, the bird becomes top-heavy and tips forward. When it dips, the bottom end of the tube opens, allowing vapor to return to the base, equalizing the pressure. The liquid then flows back down, and the bird returns upright—only for the cycle to begin again.

Key Components of the Drinking Bird

To fully understand how the drinking bird works, it’s essential to examine its main parts and their roles:

- Felt-covered head: Absorbs water and enables evaporative cooling.

- Sealed glass body: Contains volatile liquid and vapor, maintaining a closed system.

- Connecting glass tube: Allows liquid transfer between bulbs based on pressure changes.

- Methylene chloride (or similar fluid): Chosen for its low boiling point (~40°C), enabling easy phase shifts at room temperature.

- Counterweight or metal stand: Ensures the bird rocks forward and backward smoothly without falling over.

This elegant design requires no batteries or external power source, making the drinking bird a popular demonstration in physics classrooms and science museums.

Thermodynamic Principles at Play

The operation of the drinking bird is a textbook example of a heat engine—a device that converts thermal energy into mechanical work. In this case, the 'work' is the tilting motion.

The process follows these thermodynamic stages:

- Evaporation: Water on the felt head evaporates, drawing heat from the glass bulb and cooling it.

- Condensation: Cooler temperature in the head causes vapor to condense, reducing internal pressure.

- Pressure differential: Higher pressure in the warmer base pushes liquid upward.

- Center of mass shift: Rising liquid makes the head heavier, tipping the bird forward.

- Equilibration: At the lowest point, the tube opens to vapor flow, pressure equalizes, and liquid drains back.

- Reset: The bird returns upright, water re-soaks the head, and the cycle repeats.

This continuous loop will persist as long as there is water to wet the head and ambient air to allow evaporation. Humidity levels, room temperature, and air currents all influence the bird’s performance.

Factors That Affect Drinking Bird Performance

While the basic mechanism is consistent, several environmental variables impact how efficiently the drinking bird operates:

| Factor | Effect on Operation | Optimal Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Ambient Temperature | Higher temps increase evaporation rate and vapor pressure | 20–25°C (68–77°F) |

| Humidity | High humidity slows evaporation, reducing cooling effect | Below 50% RH |

| Airflow | Gentle breeze enhances evaporation; strong drafts destabilize motion | Still to light air movement |

| Water Availability | Dry head stops the cycle; shallow dish allows repeated dipping | Consistent water source at beak level |

| Fluid Integrity | Leaks or contamination disrupt pressure balance | Sealed, pure methylene chloride |

For best results, place the drinking bird in a dry, warm room with minimal drafts. If the bird stops moving, check whether the head is still damp and whether the base is cracked or leaking.

Common Misconceptions About the Drinking Bird

Despite its scientific simplicity, several myths surround the drinking bird:

- Myth: It runs forever. While it may seem perpetual, the bird stops when humidity prevents evaporation or if the fluid degrades.

- Myth: It violates the laws of thermodynamics. It does not. It consumes energy from the environment (heat and water evaporation), so it’s not a perpetual motion machine.

- Myth: Any liquid can power it. Only volatile fluids with specific vapor pressures work. Water alone won’t move the liquid inside.

- Myth: It’s alive or sentient. Some children (and adults!) believe the bird is responding consciously to thirst—this is purely anthropomorphism.

Understanding how does the drinking bird work dispels these myths and reinforces core concepts in physics education.

Educational Uses and Classroom Demonstrations

The drinking bird is widely used in science education to illustrate:

- Phase changes (liquid to gas and back)

- Heat transfer and evaporative cooling

- Gas laws (e.g., vapor pressure and temperature relationship)

- Energy conversion (thermal → mechanical)

- Simple machines and center of gravity

Teachers often pair the toy with experiments such as placing the bird under a bell jar to reduce airflow, testing different liquids on the head, or measuring cycle frequency under varying temperatures. These hands-on activities help students grasp abstract concepts through observation.

Historical Background and Invention

The drinking bird was patented in 1945 by American inventor Miles V. Sullivan, though similar devices existed earlier in China and Europe. Sullivan’s version used methylene chloride and became a commercial success, especially during the mid-20th century fascination with scientific novelties.

Originally marketed as a barroom gimmick, the toy gained popularity in laboratories and schools due to its reliable operation and clear demonstration of physical principles. Over time, it evolved into a staple of STEM outreach programs and science gift shops.

Safety and Maintenance Tips

While generally safe, users should consider the following:

- Do not break the glass: Methylene chloride is toxic if inhaled or ingested. Dispose of broken units carefully.

- Keep away from children and pets: Small parts and hazardous fluid make it unsuitable for unsupervised use.

- Avoid direct sunlight: Excessive heat can increase internal pressure and risk explosion.

- Clean gently: Wipe exterior with a damp cloth; do not submerge.

- Store properly: Keep in a cool, dry place with the head moistened occasionally to prevent drying.

If the bird stops working prematurely, inspect for leaks, ensure the head remains wettable, and verify that the pivot point moves freely.

Variants and Modern Adaptations

Over the years, manufacturers have produced variations of the classic drinking bird:

- LED-enhanced models: Include lights in the base that flash with each dip.

- Different fluids: Some use ethanol or other solvents, though less efficient than methylene chloride.

- Colored dyes: Added to the liquid for visual appeal.

- Miniature versions: Sold as keychains or desk toys.

- Double-bird systems: Two birds linked to create synchronized motion.

Despite aesthetic updates, the underlying physics remains unchanged. Collectors and educators often prefer the original design for its authenticity and reliability.

Where to Buy and What to Look For

Drinking birds are available from:

- Science education suppliers (e.g., Arbor Scientific, Educational Innovations)

- Online marketplaces (Amazon, eBay)

- Museum gift shops (especially science and technology museums)

- Toys and novelty retailers

When purchasing, look for:

- Clear glass with no cracks

- Smooth pivot mechanism

- Properly sealed system (no bubbles forming over time)

- Instructions or educational materials included

Prices typically range from $10 to $30, depending on size and features.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long can a drinking bird operate?

A well-maintained drinking bird can operate continuously for days or even weeks, as long as water is available and environmental conditions support evaporation.

Can I refill the liquid inside?

No. The system is permanently sealed. Attempting to open it releases toxic vapor and destroys the pressure balance. Replace the unit if it stops working.

Why isn’t my drinking bird moving?

Check if the head is wet, the room is too humid, or if the bird is in a draft-free zone. Also, ensure the base is level and the pivot moves freely.

Is the drinking bird a perpetual motion machine?

No. It requires an external energy source—evaporative cooling powered by ambient heat—so it doesn’t violate thermodynamic laws.

What happens if the bird breaks?

Evacuate the area, ventilate the room, and avoid inhaling fumes. Wear gloves to clean up glass and contaminated materials. Dispose of as hazardous waste if required locally.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4