Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, primarily spreads through direct contact with infected birds or their bodily fluids, including saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. One of the most common ways how does the bird flu spread is via exposure to contaminated environmentsâsuch as coops, feed, water sources, or equipment used around infected poultry. Wild migratory birds, especially waterfowl like ducks and geese, often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent transmitters across regions. This natural transmission route plays a major role in outbreaks among commercial and backyard flocks. Understanding how avian influenza spreads from birds to birds is essential for farmers, wildlife biologists, and public health officials aiming to prevent large-scale epidemics.

The Biology of Avian Influenza Viruses

Avian influenza viruses belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family and are categorized by two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, leading to various combinations such as H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8. These designations help scientists track strains and assess their potential threat level.

Low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) strains typically cause mild symptoms in birdsâruffled feathers, decreased egg production, or minor respiratory issues. However, these can mutate into highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) forms, which lead to severe illness and high mortality rates in domestic poultry. The mutation often occurs when the virus replicates within a host, particularly in environments where large numbers of birds are kept together.

The H5N1 strain has been one of the most concerning due to its ability to cross species barriers and infect humans, albeit rarely. Since its emergence in Asia in the late 1990s, it has caused periodic outbreaks worldwide, prompting global surveillance efforts.

Primary Transmission Pathways of Bird Flu

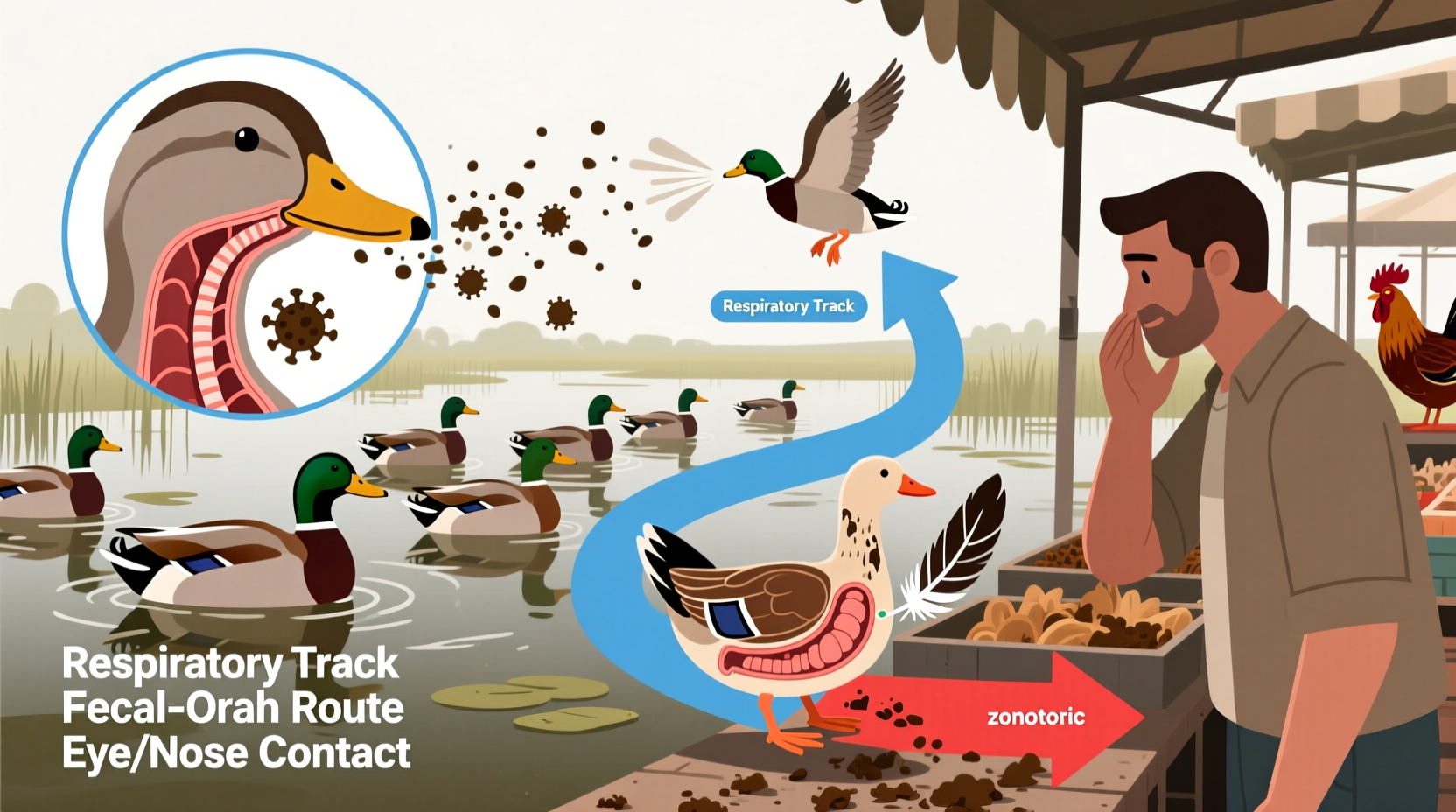

Understanding how does bird flu spread between birds involves examining several key transmission routes:

- Direct Contact: Infected birds shed the virus through excretions. Healthy birds become infected by inhaling aerosolized particles or ingesting contaminated material.

- Indirect Contact: The virus can survive on surfaces for days, especially in cool, moist conditions. Shared equipment, clothing, footwear, cages, and transport vehicles can all serve as vectors. \li>Wildlife Reservoirs: Migratory waterfowl are natural reservoirs of avian influenza. They carry the virus over long distances during seasonal migrations, introducing it to new areas.

- Airborne Transmission: In enclosed spaces like barns or poultry houses, the virus may spread through airborne droplets, particularly in high-density farming operations.

Notably, while wild birds often remain asymptomatic, domesticated birdsâespecially chickens and turkeysâare highly susceptible to severe disease. This disparity underscores the importance of biosecurity measures on farms located near wetlands or migratory flyways.

Human Infection: How Does Bird Flu Spread to People?

Although human cases remain rare, understanding how bird flu spreads to humans is critical for public health planning. Most infections occur through close contact with infected live or dead birds, particularly during slaughtering, defeathering, or handling contaminated products.

There is currently no sustained human-to-human transmission of bird flu. However, sporadic cases have occurred, mainly in individuals working directly with poultry in affected regions. For example, people involved in backyard farming, live bird markets, or culling operations face higher exposure risks.

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that while the risk to the general public remains low, vigilance is necessary because influenza viruses can evolve rapidly. If a strain gains the ability to transmit efficiently between humans, it could trigger a pandemic. Therefore, monitoring zoonotic spillover events is a global priority.

Role of Migration and Climate in Bird Flu Spread

Migratory patterns significantly influence how avian flu spreads across continents. Each year, millions of birds travel along established flywaysâsuch as the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways in North Americaâcarrying pathogens with them.

During spring and fall migrations, infected birds can introduce the virus into new ecosystems, contaminating lakes, ponds, and agricultural zones. Cooler temperatures prolong the survival of the virus in the environment, increasing transmission windows. Warmer climates tend to reduce viral persistence, but humidity and shade can still support its longevity.

Climate change may be altering traditional migration routes and timing, potentially expanding the geographic range of avian influenza. Changes in precipitation, temperature, and habitat availability affect both bird behavior and virus stability, creating unpredictable dynamics for outbreak forecasting.

Outbreak Management and Surveillance Systems

Governments and international agencies maintain robust surveillance networks to detect and respond to bird flu outbreaks. Programs like the USDAâs National Poultry Improvement Plan (NPIP) and the OIEâs (World Organisation for Animal Health) global reporting system enable rapid identification and containment.

When an outbreak occurs, authorities typically implement:

- Immediate culling of infected and exposed flocks

- Establishment of control zones with movement restrictions

- Enhanced biosecurity protocols for nearby farms

- Surveillance of wild bird populations near outbreak sites

In the U.S., state departments of agriculture work closely with federal agencies to coordinate responses. Early detection through routine testing helps limit economic losses and protects food security.

| Transmission Route | Description | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Bird-to-Bird | Virus spreads via secretions and feces in close proximity | Isolate sick birds; avoid overcrowding |

| Contaminated Surfaces | Virus survives on tools, shoes, crates, etc. | Disinfect equipment; use dedicated farm attire |

| Wild Bird Exposure | Migratory birds introduce virus to poultry | Secure housing; cover outdoor runs |

| Human-Mediated Spread | People move virus on clothes or vehicles | Implement strict biosecurity protocols |

| Airborne in Confined Spaces | Droplet transmission in barns | Improve ventilation; reduce flock density |

Protecting Backyard Flocks and Commercial Farms

Backyard poultry owners play a crucial role in preventing local outbreaks. Simple practices can drastically reduce the risk of infection:

- Keep birds indoors during peak migration seasons or when bird flu alerts are active in your region.

- Avoid visiting other poultry farms or bird exhibitions without changing clothes and disinfecting footwear afterward.

- Source chicks from certified disease-free hatcheries and quarantine new birds before integrating them into existing flocks.

- Use separate footwear and clothing for handling birds, and wash hands thoroughly after contact.

- Report sudden deaths or signs of illnessâsuch as swollen heads, purple discoloration, or neurological symptomsâto local veterinary authorities immediately.

Commercial operations should follow comprehensive biosecurity plans, including visitor logs, vehicle decontamination stations, and air filtration systems where applicable. Employee training is vital to ensure consistent adherence to protocols.

Food Safety and Public Perception

A common misconception is that eating poultry or eggs can transmit bird flu. According to the CDC and FDA, properly cooked meat and pasteurized eggs pose no risk. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 165°F (74°C).

However, cross-contamination during food preparation remains a theoretical concern. Consumers should:

- Wash cutting boards, knives, and hands after handling raw poultry

- Cook eggs until yolks and whites are firm

- Avoid consuming raw or undercooked eggs from areas experiencing outbreaks

Despite safety assurances, consumer confidence often drops during outbreaks, impacting market prices and farmer livelihoods. Transparent communication from health agencies helps mitigate panic and misinformation.

Global Trends and Recent Outbreaks

The 2022â2023 avian influenza season saw one of the largest outbreaks in U.S. history, affecting over 58 million birds across 47 states. The H5N1 strain was responsible, likely introduced via wild birds from Europe and Asia.

Europe also experienced widespread infections, with countries like France, Germany, and the UK imposing mandatory indoor confinement orders for poultry. In Asia, ongoing circulation of multiple strains in live bird markets continues to challenge eradication efforts.

These recurring outbreaks highlight the need for international cooperation in surveillance, data sharing, and vaccine development. While vaccines exist for some strains, they are not universally effective due to antigenic driftâthe process by which viruses mutate over time.

Myths vs. Facts About Bird Flu Transmission

Several myths persist about how bird flu spreads in nature, leading to unnecessary fear or complacency.

Myth: All birds die quickly from bird flu.

Fact: Many wild birds, especially ducks, carry the virus without symptoms and can spread it widely.

Myth: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Turkeys, guinea fowl, quail, and even pet parrots can become infected.

Myth: You can catch bird flu from watching wild birds.

Fact: Casual observation poses no risk. Transmission requires direct contact with infected birds or their waste.

Myth: Thereâs a human vaccine available for bird flu.

Fact: Experimental vaccines exist but are not publicly distributed. Seasonal flu shots do not protect against avian strains.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can you get bird flu from eating chicken?

- No, as long as the meat is properly cooked to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C), the virus is destroyed and poses no risk.

- How long does bird flu live on surfaces?

- The virus can survive for up to 7 days in moist environments at room temperature, and longer in cold or shaded areas.

- Are songbirds carriers of bird flu?

- Yes, though less commonly than waterfowl, some songbirds and raptors have tested positive during outbreaks.

- What should I do if I find a dead wild bird?

- Do not touch it. Report it to your local wildlife agency or department of natural resources for safe collection and testing.

- Is there a cure for bird flu in birds?

- There is no treatment. Infected flocks are culled to prevent further spread and protect public health.

In conclusion, understanding how does the bird flu spread involves recognizing the complex interplay between wild bird migration, poultry farming practices, environmental factors, and human activity. By combining scientific knowledge with practical prevention strategies, we can reduce the impact of avian influenza on wildlife, agriculture, and public health. Continued research, global collaboration, and community awareness remain our strongest defenses against future outbreaks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4