Bird flu, or avian influenza, is primarily contracted through direct contact with infected birds or their bodily fluids, including saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. A natural longtail keyword variant of how is bird flu contracted includes 'how do humans get bird flu from chickens or wild birds.' This highly contagious viral disease spreads most commonly among bird populations but can also jump to humans and other animals under specific conditions. The H5N1 and H7N9 strains are among the most well-documented subtypes known for zoonotic transmission. Understanding how bird flu is contracted is essential for farmers, poultry workers, wildlife biologists, and birdwatchers who may come into close proximity with avian species.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Virus Types

Avian influenza viruses belong to the influenza A family, which is categorized based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, resulting in numerous combinations such as H5N1, H7N9, and H9N2. These viruses naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds—particularly ducks, geese, and shorebirds—which often carry the virus without showing symptoms.

The first recorded outbreak of avian influenza dates back to 1878 in Italy, though it wasn't until the late 20th century that scientists began identifying specific strains capable of crossing species barriers. The emergence of the H5N1 strain in Hong Kong in 1997 marked a turning point, as it was the first time this virus was shown to cause severe illness and death in otherwise healthy humans. Since then, multiple outbreaks across Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America have highlighted the global threat posed by how bird flu is contracted and transmitted.

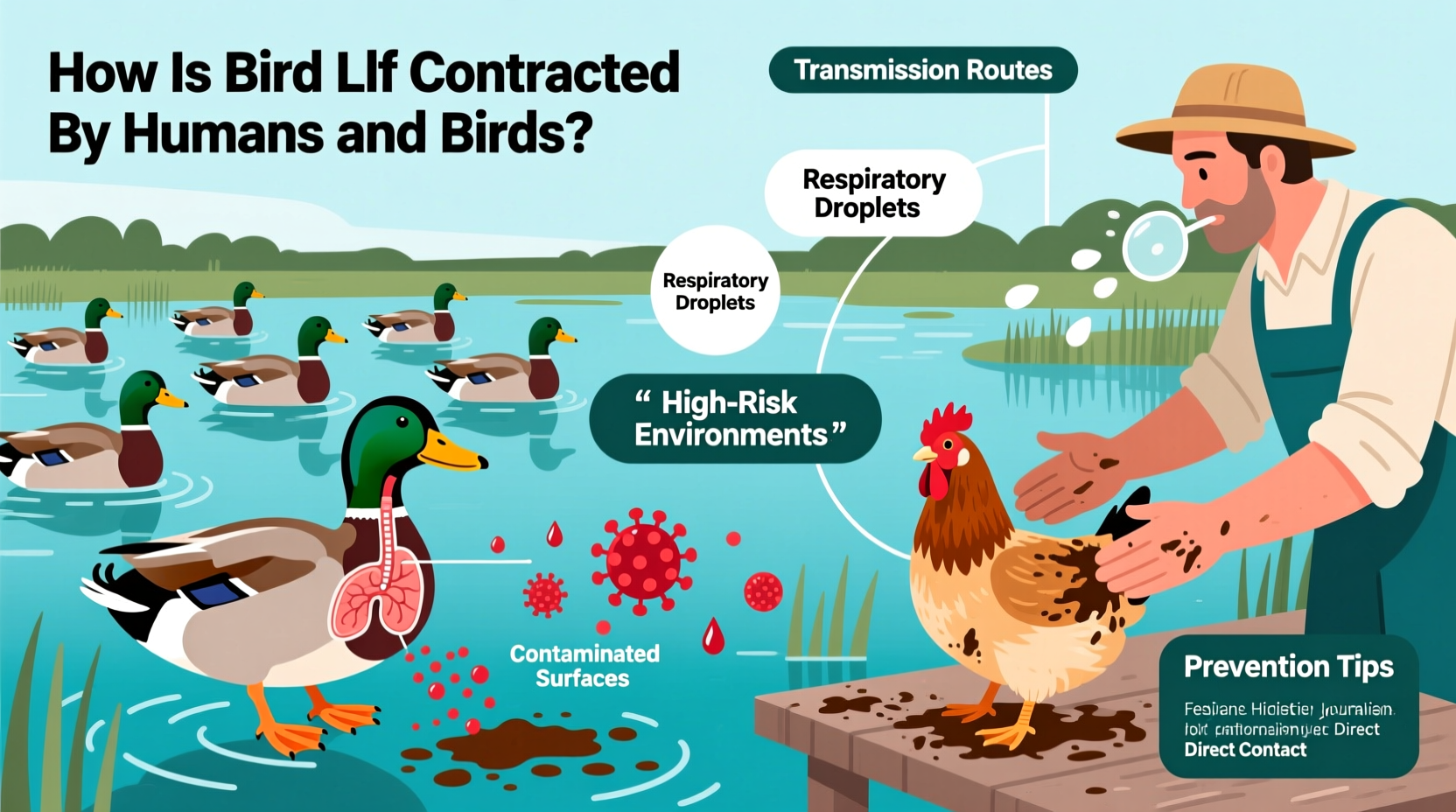

Primary Transmission Pathways Among Birds

Within bird populations, especially in dense environments like commercial poultry farms or migratory stopover sites, bird flu spreads rapidly. The main routes include:

- Direct contact: Healthy birds become infected when they touch sick birds.

- Fecal-oral route: Viral particles in infected droppings contaminate water, feed, or soil, which are then ingested by other birds.

- Aerosol transmission: In enclosed spaces such as barns, the virus can spread via respiratory droplets released during coughing or sneezing.

- Contaminated equipment or clothing: Farmers, veterinarians, or transporters can inadvertently carry the virus on boots, tools, or vehicles.

Wild birds, particularly those migrating over long distances, play a crucial role in spreading the virus across regions. While many remain asymptomatic carriers, they shed the virus in their feces, contaminating wetlands and agricultural areas where domestic flocks may later come into contact.

How Do Humans Contract Bird Flu?

Although human cases remain relatively rare, understanding how bird flu is contracted by people is vital for public health preparedness. Most infections occur in individuals with prolonged, unprotected exposure to infected birds or contaminated environments. Key risk factors include:

- Killing, defeathering, or preparing infected poultry for cooking

- Working in live bird markets where hygiene standards are poor

- Cleaning coops or handling manure without protective gear

- Living in close quarters with backyard poultry flocks

It's important to note that consuming properly cooked poultry or eggs does not transmit the virus. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirms that heating meat to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) kills the avian influenza virus. However, cross-contamination during food preparation remains a concern if cutting boards or utensils used for raw poultry are not thoroughly cleaned.

To date, sustained human-to-human transmission has been extremely limited. Most cases involve isolated incidents rather than community spread, reducing the likelihood of a pandemic—but virologists continue monitoring mutations that could enhance transmissibility.

High-Risk Regions and Seasonal Patterns

Bird flu outbreaks tend to follow seasonal patterns, peaking during colder months when wild birds migrate southward and come into closer contact with domestic flocks. Countries with large poultry industries and overlapping wild bird habitats—such as China, India, Indonesia, Egypt, Nigeria, and parts of Eastern Europe—are more prone to recurring outbreaks.

In North America, surveillance programs led by agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) monitor migratory bird populations and test dead birds found in urban and rural areas. For example, in early 2022, a significant H5N1 outbreak affected millions of commercial turkeys and chickens across the United States, prompting temporary export restrictions and heightened biosecurity measures.

Climate change may be influencing these patterns by altering migration timelines and expanding the geographic range of certain bird species, thereby increasing opportunities for viral spillover.

Common Misconceptions About How Bird Flu Is Contracted

Several myths persist about avian influenza transmission. Addressing these misconceptions helps reduce unnecessary fear and promotes accurate preventive behaviors:

- Myth: You can catch bird flu from eating chicken or eggs.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry products pose no risk. The virus is destroyed at high temperatures. - Myth: All bird species carry deadly strains of avian flu.

Fact: Most wild birds don’t show symptoms and only a few subtypes are highly pathogenic. - Myth: Pet birds like parrots or canaries easily spread the virus to humans.

Fact: Companion birds are rarely involved in transmission unless exposed to infected wild or farm birds. - Myth: Bird flu spreads easily between people.

Fact: Human-to-human transmission is rare and typically requires very close, prolonged contact.

Prevention Strategies for Poultry Workers and Farmers

For those working in agriculture or animal husbandry, minimizing exposure is key. Recommended practices include:

- Wearing gloves, masks, and protective clothing when handling birds

- Regularly disinfecting coops, cages, and equipment using approved virucidal agents

- Isolating new or sick birds immediately

- Reporting unusual bird deaths to local veterinary authorities

- Vaccinating poultry where approved and effective vaccines are available

Many countries enforce strict biosecurity protocols during outbreak periods, including movement bans on live birds and mandatory culling of infected flocks. While controversial, these measures aim to contain the virus before it spreads further.

What Birdwatchers and Outdoor Enthusiasts Should Know

Recreational birdwatchers generally face low risk, but precautions are still advised, especially during active outbreaks. Tips include:

- Avoid touching sick or dead birds; report them to wildlife agencies

- Use binoculars instead of approaching nests or roosting areas

- Do not feed waterfowl in areas with known infections

- Wash hands after outdoor activities near wetlands or farms

- Disinfect boots and gear after visiting bird sanctuaries or rural zones

National parks and conservation areas may temporarily close certain trails or viewing platforms during outbreaks. Checking official websites such as the Audubon Society, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, or government wildlife departments ensures up-to-date guidance on safe birding practices.

Diagnosis and Treatment Options

In humans, symptoms of bird flu resemble severe influenza: high fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and sometimes pneumonia or acute respiratory distress. Anyone experiencing these signs after potential exposure should seek medical attention immediately.

Diagnostic tests involve collecting respiratory samples (nasopharyngeal swabs) for RT-PCR analysis. Antiviral medications like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) may reduce severity if administered early. However, antiviral resistance has been observed in some strains, underscoring the need for ongoing research.

There is currently no widely available vaccine for humans against H5N1, although experimental formulations are being tested in clinical trials. Seasonal flu shots do not protect against avian influenza but are still recommended to reduce complications from co-infections.

Global Surveillance and Future Outlook

Organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO), World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) collaborate on global surveillance networks to detect and respond to avian influenza threats. Early warning systems use satellite tracking of bird migrations, genetic sequencing of virus samples, and real-time reporting from member states.

Despite advances, challenges remain. Limited veterinary infrastructure in developing nations hampers rapid detection and response. Additionally, illegal poultry trade and lack of farmer education contribute to uncontrolled spread.

Future efforts will focus on improving diagnostics, expanding vaccination coverage in poultry, enhancing international cooperation, and studying viral evolution to predict dangerous mutations.

| Transmission Route | Risk Level (Humans) | Prevention Method |

|---|---|---|

| Contact with infected poultry feces | High (for poultry workers) | Wear protective gear, sanitize tools |

| Inhaling aerosols in enclosed barns | Moderate | Use masks, ensure ventilation |

| Eating cooked poultry/eggs | None | Cook to 165°F (74°C) |

| Touching dead wild birds | Low to moderate | Use gloves, report to authorities |

| Human-to-human contact | Very rare | Isolate infected individuals |

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can you get bird flu from pet birds?

- It’s unlikely unless your pet bird has been exposed to infected wild or farm birds. Indoor birds kept away from external sources pose minimal risk.

- Is there a bird flu vaccine for humans?

- Not yet available for general use. Experimental vaccines exist for stockpiling purposes in case of a pandemic, but they are not part of routine immunization.

- How long does the bird flu virus survive in the environment?

- The virus can remain infectious for days to weeks depending on conditions. In cool, moist environments like pond water or shaded soil, it may last up to 30 days.

- Are all bird species equally susceptible?

- No. Waterfowl often carry the virus without getting sick, while chickens and turkeys are highly vulnerable and may die within 48 hours of infection.

- What should I do if I find a dead bird?

- Do not handle it barehanded. Contact your local wildlife agency or health department for instructions on reporting and disposal.

Understanding how bird flu is contracted empowers individuals and communities to take informed actions. Whether you're a poultry farmer, biologist, or nature lover, staying educated about transmission pathways, practicing good hygiene, and following public health advisories are critical steps in preventing future outbreaks.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4