Bird flu, or avian influenza, can remain viable on surfaces for up to 2 weeks under favorable conditions. The exact duration depends heavily on environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and the type of surface involved. For example, how long does bird flu live on surfaces in cold, moist environments? In cooler temperatures—especially below 4°C (39°F)—the virus can persist much longer, particularly on non-porous materials like metal, plastic, or concrete. This makes areas such as poultry farms, bird markets, and outdoor enclosures high-risk zones for indirect transmission. Understanding the lifespan of avian influenza on various surfaces is essential for preventing outbreaks among wild birds, domestic poultry, and even humans who come into contact with contaminated environments.

Understanding Avian Influenza: A Biological Overview

Bird flu is caused by Type A influenza viruses, primarily affecting birds but with some strains capable of infecting mammals, including humans. These viruses are classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N), leading to subtypes such as H5N1, H7N9, and H5N8. While most strains circulate among wild waterfowl—particularly ducks, geese, and shorebirds—they can spill over into domestic poultry populations, causing severe illness and high mortality rates.

The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds or their bodily fluids, including saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. However, an equally important route of transmission is indirect: via contaminated surfaces. When an infected bird sheds the virus, it can land on feeders, cages, soil, water sources, or farming equipment. Healthy birds—or people—can then pick up the virus by touching these surfaces and transferring it to mucous membranes.

Factors That Influence How Long Bird Flu Survives on Surfaces

The persistence of avian influenza outside a host varies widely depending on several key variables:

- Temperature: The virus remains stable longer at lower temperatures. At refrigeration levels (around 4°C), it may survive for up to 14 days. In contrast, at room temperature (20–25°C), survival drops significantly—typically between 24 hours and 7 days.

- Humidity: Moderate to high humidity supports longer viral stability, especially when combined with cooler temperatures. Dry conditions tend to degrade the virus more quickly.

- Surface Type: Non-porous surfaces like stainless steel, plastic, glass, and rubber allow the virus to remain infectious longer than porous materials such as wood, fabric, or paper. Moisture retention plays a role here; damp feed troughs or wet cages pose higher risks.

- Sunlight (UV Exposure): Ultraviolet radiation from sunlight has a deactivating effect on the virus. Outdoor surfaces exposed to direct sunlight generally harbor the virus for shorter durations than shaded or indoor areas.

- pH and Organic Matter: The presence of organic material (e.g., feces, mucus, soil) can protect the virus from degradation. Environments rich in biological residue—like barn floors or untreated water sources—may prolong viability.

For instance, studies have shown that the H5N1 strain can survive in lake water for up to 4 days at 22°C but for over 200 days at 0°C. Similarly, on feathers, the virus may persist for weeks, making discarded plumage a potential vector in wild bird habitats.

Survival Times by Surface Type and Environment

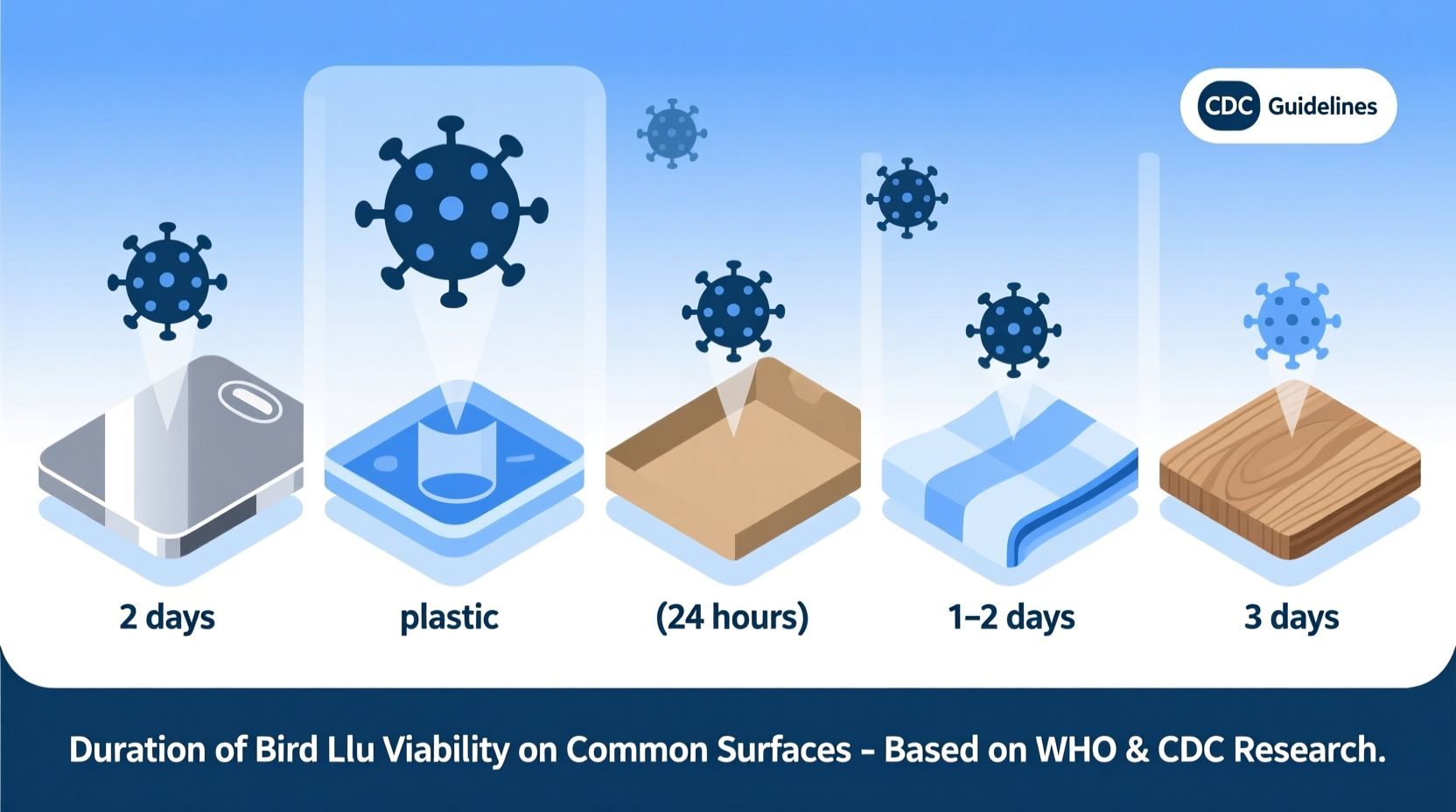

To better understand real-world risk, consider this breakdown of how long bird flu can remain active under different conditions:

| Surface/Environment | Temperature Range | Average Survival Time | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stainless Steel | 4°C (refrigerated) | Up to 14 days | Common in cages, tools, transport vehicles |

| Plastic | 20–25°C (room temp) | 2–7 days | Bird feeders, water containers, crates |

| Soil | 4–10°C (cool, moist) | 7–21 days | Risk increases in shaded, damp areas |

| Feces (on surfaces) | 4°C | 30–40 days | Virus protected by organic matter |

| Feathers | Room temp | Up to 16 days | Natural reservoirs in wild bird populations |

| Freshwater (lakes, ponds) | 0°C | Over 200 days | Major concern for migratory waterfowl |

| Cardboard/Paper | Room temp | 12–24 hours | Low risk due to absorbency and dryness |

Cultural and Symbolic Context of Birds and Disease

Birds have long held symbolic significance across cultures—from messengers of the divine to omens of change. In many traditions, crows, ravens, and owls are associated with death or transformation, while doves symbolize peace and renewal. However, during disease outbreaks like those caused by bird flu, public perception often shifts dramatically. Fear of contamination leads to stigmatization of both wild birds and poultry farming communities.

This cultural tension underscores the importance of science-based education. While birds play vital ecological roles as pollinators, seed dispersers, and pest controllers, they also serve as natural reservoirs for certain pathogens. Rather than vilifying them, societies must balance reverence for nature with responsible biosecurity practices. Recognizing how long bird flu lives on surfaces empowers individuals to coexist safely with avian life without unnecessary fear.

Practical Guidance for Preventing Transmission via Contaminated Surfaces

Whether you're a backyard chicken keeper, a wildlife rehabilitator, or an avid birder, minimizing exposure to contaminated surfaces is crucial. Here are actionable steps to reduce risk:

- Regularly Disinfect Equipment: Use EPA-approved disinfectants effective against influenza viruses (e.g., bleach solutions at 1:10 dilution). Clean feeders, waterers, cages, boots, and gloves weekly—or immediately after contact with wild birds.

- Practice Good Hygiene: Always wash hands thoroughly with soap and water after handling birds or visiting areas where birds congregate. Avoid touching your face until hands are clean.

- Limit Wild Bird Contact: Keep domestic poultry separated from wild birds. Cover outdoor runs and avoid placing feeders near poultry housing.

- Dispose of Waste Safely: Compost manure at high temperatures (>60°C) to kill pathogens. Do not spread raw poultry waste on gardens or fields accessible to wild birds.

- Monitor Local Outbreaks: Stay informed through national agricultural departments or wildlife agencies about local avian influenza activity. Restrict movement of birds during outbreak periods.

- Use Protective Gear: When cleaning potentially contaminated areas, wear disposable gloves, masks, and eye protection to prevent inhalation or accidental ingestion of viral particles.

Misconceptions About Bird Flu Survival and Spread

Several myths persist about how long bird flu lives on surfaces and how it spreads:

- Myth: The virus can survive indefinitely on all surfaces.

Fact: While durable under cold, wet conditions, the virus degrades rapidly in heat, dryness, and UV light. - Myth: Only live birds transmit the disease.

Fact: Fomites—objects or materials likely to carry infection—are major contributors. Shoes, tires, and tools can transport the virus across regions. - Myth: Cooking poultry eliminates surface contamination risks.

Fact: While cooking kills the virus in meat, cross-contamination from cutting boards, knives, or packaging remains a hazard if proper sanitation isn’t followed. - Myth: Urban areas are safe from bird flu.

Fact: Parks, fountains, and backyard feeders can become contaminated, especially if shared by migratory and domestic birds.

Regional Differences in Risk and Response

The duration and impact of bird flu on surfaces vary globally due to climate, farming practices, and surveillance systems. In colder regions like Northern Europe or Canada, winter months see prolonged viral persistence in outdoor environments. In contrast, tropical climates with high temperatures and intense sunlight may limit surface survival to just a few hours.

Additionally, countries with dense poultry industries—such as the United States, China, and parts of Southeast Asia—often implement strict biosecurity protocols, including mandatory disinfection zones and movement restrictions during outbreaks. Meanwhile, rural or resource-limited areas may lack access to testing or protective supplies, increasing vulnerability.

Travelers, farmers, and bird enthusiasts should consult local health and agriculture authorities before entering high-risk zones. Checking official websites for updates on avian influenza detections helps inform decisions about birdwatching trips, farm visits, or pet bird care.

FAQs: Common Questions About Bird Flu Survival on Surfaces

How long does bird flu live on clothes?

The virus typically survives on fabric for 8–12 hours, depending on moisture and temperature. Washing clothes in hot water (>60°C) with detergent effectively destroys the virus.

Can I get bird flu from touching a bird feeder?

While rare, it’s possible if the feeder was recently contaminated by infected wild birds. Regular cleaning and handwashing minimize this risk significantly.

Does rain wash away the bird flu virus?

Rain can dilute and disperse the virus, but it doesn’t instantly eliminate it. In fact, runoff water can spread the virus to new locations, especially in low-lying or flooded areas.

Is freezing effective at killing bird flu?

No—freezing preserves the virus rather than destroying it. Thawing contaminated materials can reactivate the pathogen. Proper cooking (internal temperature of 74°C/165°F) is required to ensure safety.

How often should I clean my bird feeder to prevent bird flu?

Clean feeders at least once every two weeks using a 10% bleach solution. During known outbreaks, increase frequency to weekly and monitor nearby bird health.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4