Preserving a dead bird can be accomplished through methods such as taxidermy, freeze-drying, or creating study skins, but it must be done legally and ethically. A common longtail keyword variant like 'how to properly preserve a dead bird for educational use' reflects the growing interest among bird enthusiasts, educators, and amateur naturalists in maintaining avian specimens for study or display. However, before attempting any preservation technique, it is essential to understand federal and state regulations—especially in the United States under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), which prohibits the possession of most native bird species, including their feathers, nests, and eggs, without proper permits.

Understanding the Legal Framework

Before discussing techniques on how to preserve a dead bird, one must first address legality. In the U.S., the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 protects over 1,000 species of birds, making it illegal to collect, possess, or preserve them without authorization from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). This includes not only live birds but also deceased individuals, molted feathers, and abandoned nests.

Exceptions exist for certain non-native species such as European starlings, house sparrows, and rock pigeons, which are not protected under the MBTA. If you find a dead bird belonging to one of these species, preservation may proceed without a permit. However, even with exempt species, local laws may impose additional restrictions, so always verify with your state’s wildlife agency.

Permits for preserving birds are typically issued only to qualified institutions or individuals engaged in scientific research, education, or rehabilitation. These include museums, universities, licensed taxidermists, and certified wildlife rehabilitators. The application process involves demonstrating legitimate need, proper storage facilities, and adherence to ethical standards.

When Is It Legal to Collect a Dead Bird?

- Naturally deceased native birds: Generally prohibited unless found during permitted activities (e.g., roadkill surveys with authorization).

- Injured birds that die in rehabilitation care: Licensed facilities may preserve remains for educational purposes with proper documentation.

- Non-native invasive species: Starlings, house sparrows, and feral pigeons may be collected and preserved legally in many jurisdictions.

- Birds killed by accidental window strikes: Possession still violates the MBTA unless reported and permitted.

If you discover a dead bird and wish to preserve it, contact your local wildlife agency or a licensed taxidermist for guidance. Unauthorized possession—even with good intentions—can result in fines up to $15,000 and six months in prison per violation.

Common Methods of Bird Preservation

Assuming legal clearance, several professional methods exist for preserving birds. Each has advantages depending on the intended use—display, scientific study, or personal collection.

1. Taxidermy

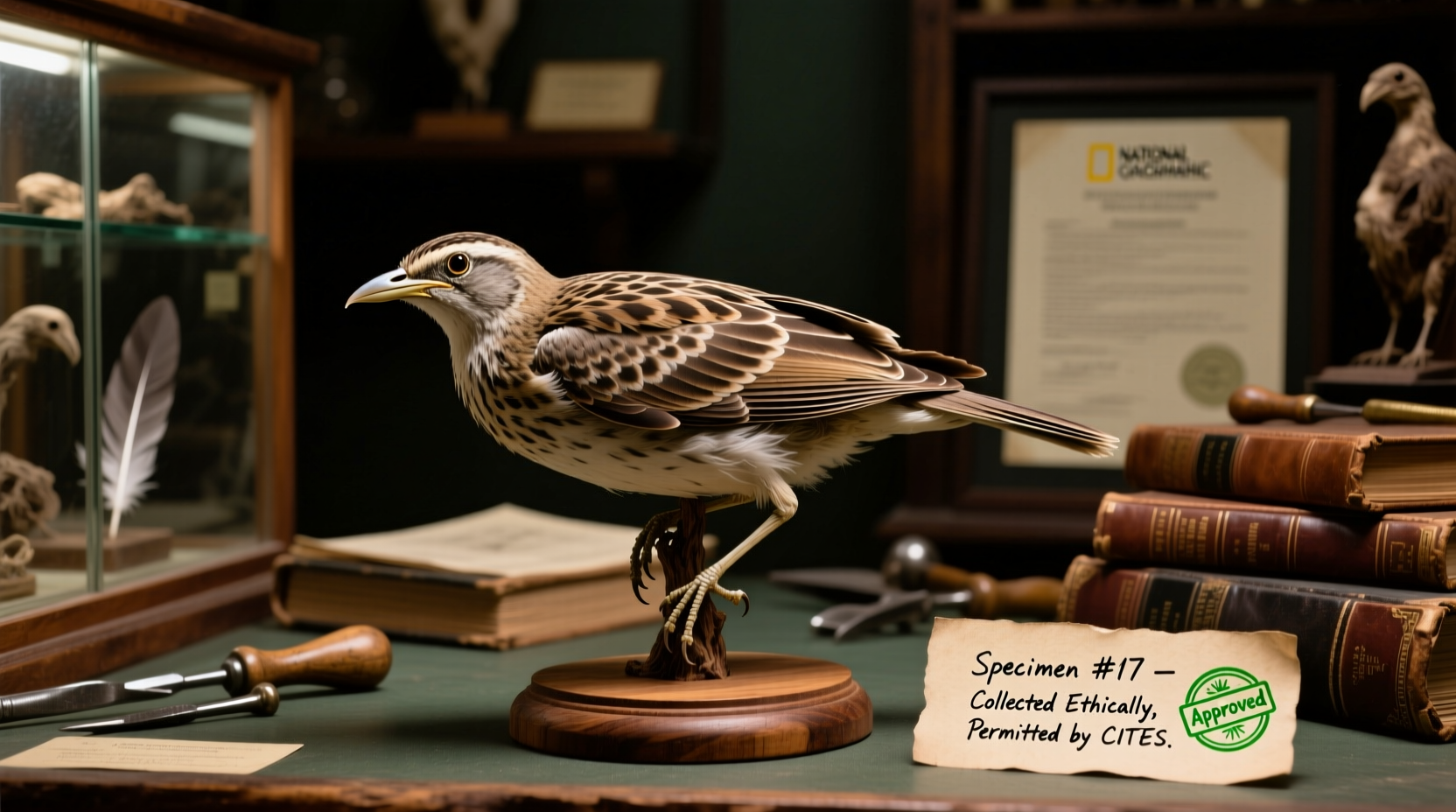

Taxidermy is the most recognized method of preserving a dead bird, involving skinning, treating the hide, and mounting it over an artificial body form. This results in a lifelike representation suitable for museums or private collections.

Steps involved:

- Skinning: Carefully remove feathers and soft tissue while preserving the skin, beak, legs, and eyes.

- Tanning: Treat the skin with preservatives to prevent decay and insect infestation.

- Mounting: Attach the skin to a mannequin shaped like the bird’s original anatomy.

- Detailing: Position wings, tail, and head into natural poses; insert glass eyes.

This method requires advanced skill and tools. Most individuals hire licensed taxidermists who specialize in avian specimens. Costs vary widely based on species size and complexity, ranging from $200 to over $1,000.

2. Freeze-Drying

Freeze-drying uses sublimation to remove moisture from the bird’s body while maintaining its three-dimensional shape. Unlike traditional taxidermy, this method preserves internal tissues and allows for more anatomically accurate mounts.

Advantages include minimal distortion and excellent feather retention. However, freeze-drying equipment is expensive and often limited to professional labs. It's commonly used for rare or delicate specimens where anatomical precision is critical.

3. Study Skins

Used primarily in scientific research, study skins are flat-mounted specimens designed for long-term archival storage in museum collections. They lack the visual appeal of taxidermy but provide valuable data on plumage, sex, age, and morphology.

Process overview:

- Carefully skin the bird, removing all internal organs.

- Preserve the skull and selected bones separately in labeled vials.

- Stuff the body cavity with cotton to maintain shape.

- Sew the incision closed and position the bird flat with wings tucked.

- Label with collection date, location, species, sex, and collector name.

Study skins are stored in climate-controlled cabinets to prevent mold and pest damage. Institutions use them for genetic analysis, comparative anatomy, and historical record-keeping.

4. Alcohol Preservation

For small birds or specific parts (like embryos or organs), immersion in ethanol (typically 70%) is effective. This method halts decomposition and maintains tissue integrity for laboratory examination.

Whole-body alcohol preservation is uncommon due to shrinkage and discoloration but remains useful for biological research. Specimens must be kept in sealed, clearly labeled containers away from light and heat.

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Prepare a Bird for Preservation (If Legally Permitted)

Whether working with a taxidermist or preparing a specimen for institutional donation, proper handling ensures quality preservation.

- Document Immediately: Record the exact time, date, GPS coordinates, habitat type, and cause of death if known. Take photographs from multiple angles.

- Refrigerate Promptly: Place the bird in a sealed plastic bag and store it in a refrigerator at 35–40°F (2–4°C). Do not freeze unless instructed by a professional, as ice crystals can damage tissues and feathers.

- Avoid Contamination: Wear gloves when handling. Avoid cleaning or washing the bird, as oils and dirt may contain forensic or ecological data.

- Contact Authorities: Report the find to a wildlife biologist, museum curator, or permitted taxidermist. Provide your documentation.

- Transport Safely: Use a rigid container to prevent crushing. Keep refrigerated during transit.

Regional Differences and Permitting Variations

Laws regarding bird preservation differ across countries and even within U.S. states. For example:

| Region | Protected Species? | Permit Required? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Yes (MBTA) | Yes (for native species) | Federal law overrides state rules; penalties apply nationwide. |

| Canada | Yes (Migratory Birds Convention Act) | Yes | Permits issued by Environment and Climate Change Canada. |

| United Kingdom | Yes (Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981) | Yes | Licensed collectors may hold certain species under Natural England. |

| Australia | Yes (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act) | Yes | Strict controls; indigenous species cannot be exported. |

In some rural areas, enforcement may appear lax, but legal risk remains. Always assume protection applies until confirmed otherwise.

Common Misconceptions About Preserving Dead Birds

- Myth: 'If I find a dead bird, I can keep it as a souvenir.'

- Truth: Even decorative use requires permits for protected species.

- Myth: 'Feathers are harmless to collect.'

- Truth: Feathers of native birds are legally protected under the MBTA.

- Myth: 'Roadkill birds are fair game.'

- Truth: Death by vehicle does not exempt the specimen from legal protections.

- Myth: 'Taxidermy kits allow anyone to preserve birds.'

- Truth: Commercial kits do not override wildlife laws; legality depends on species and jurisdiction.

Ethical Considerations in Avian Specimen Preservation

Beyond legality, ethical questions arise. Is the purpose educational or purely aesthetic? Could digital photography serve the same function without removing the bird from nature? Modern technology offers alternatives—high-resolution images, 3D scanning, and virtual dissection—that reduce reliance on physical specimens.

Responsible preservation respects both the individual animal and ecosystem balance. It should contribute to knowledge, conservation, or public education—not mere decoration.

Alternatives to Physical Preservation

- Photograph the bird in situ before reporting it to citizen science platforms like eBird or iNaturalist.

- Create a field journal entry detailing behavior, habitat, and identification clues.

- Donate the specimen to a university or nature center for research or educational programming.

- Use augmented reality apps that simulate bird anatomy and plumage variation.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can I preserve a dead cardinal I found in my backyard?

- No, northern cardinals are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Possession, even of a deceased individual, requires a federal permit.

- What should I do if I find a dead owl?

- Do not touch or move it. Contact your local wildlife rehabilitator or state fish and game office. Owls are federally protected and may carry diseases like rabies or avian influenza.

- Are there any birds I can legally preserve without a permit?

- Yes—non-native species such as European starlings, house sparrows, and rock pigeons may be collected in most U.S. states without a permit, though local ordinances may apply.

- How quickly must I act after finding a dead bird?

- Begin preservation efforts or refrigeration within 2–4 hours to prevent bloating, feather loss, and bacterial degradation.

- Can schools preserve birds for science class?

- Only with proper salvage permits issued by the USFWS. Educational institutions must demonstrate secure storage and curriculum integration.

In summary, knowing how to preserve a dead bird involves far more than technical skill—it demands awareness of legal boundaries, ethical responsibility, and ecological context. Whether your goal is scientific study, artistic expression, or personal remembrance, always prioritize compliance with wildlife laws and respect for nature. When in doubt, consult a professional or contribute your observation to citizen science instead of retaining the specimen.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4