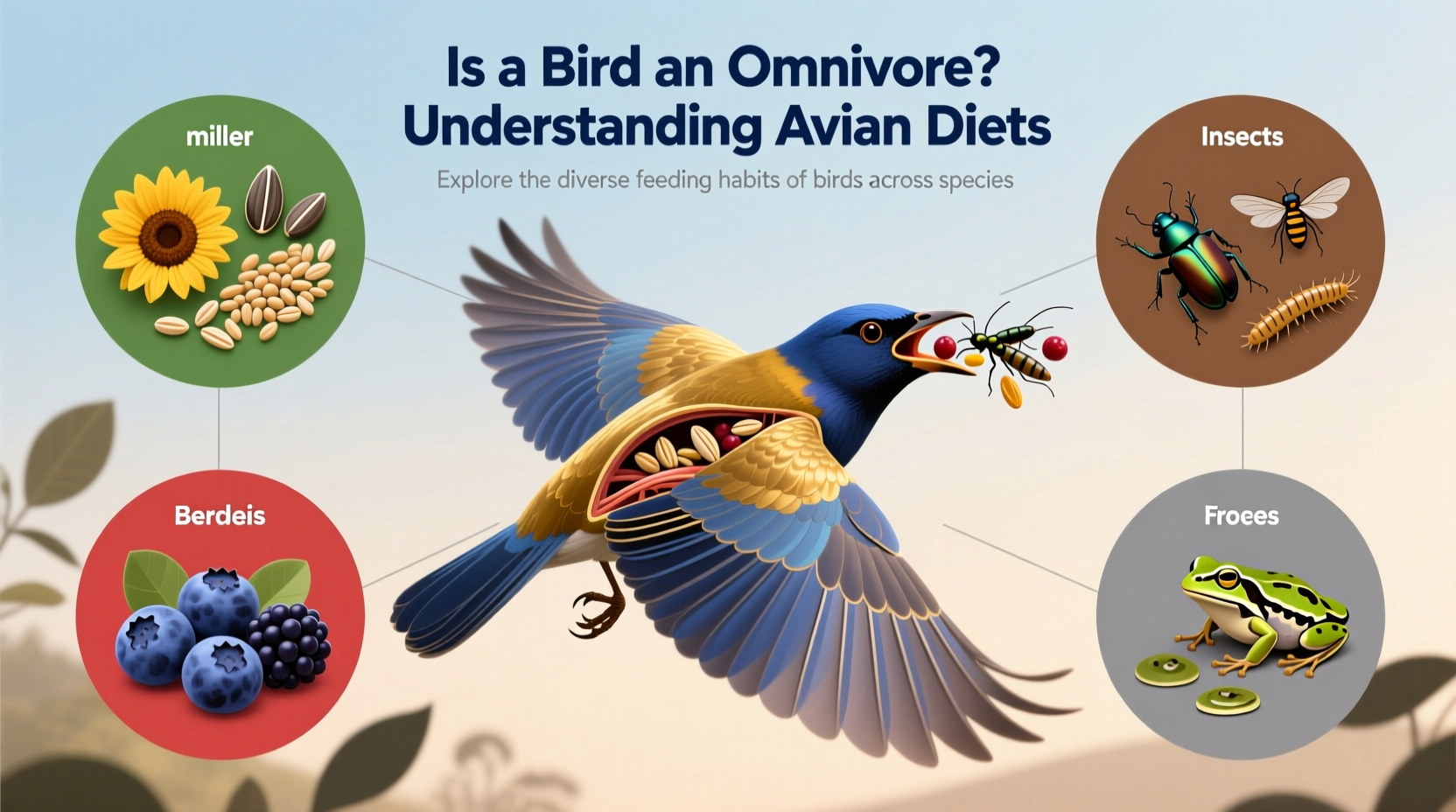

Yes, some birds are omnivores, meaning they consume both plant and animal matter to meet their nutritional needs. While not all birds fall into this category, many common speciesâincluding robins, crows, jays, and certain ducksâare classified as omnivorous due to their varied diets. This natural adaptability in feeding behavior allows omnivorous birds to thrive in diverse environments, from urban backyards to forested regions. A key longtail keyword variant here is "are most backyard birds omnivores," which reflects the curiosity of birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts trying to understand avian feeding patterns.

The Biological Basis of Bird Diets

Birds belong to the class Aves, a diverse group with over 10,000 species exhibiting a wide range of dietary strategies. These include herbivory (plant-eating), carnivory (meat-eating), granivory (seed-eating), nectarivory (nectar-feeding), and omnivory. The classification of a bird as an omnivore depends on its ability to digest and derive nutrients from both plant-based materialsâsuch as fruits, seeds, and nectarâand animal sources like insects, worms, small amphibians, and even eggs.

Omnivorous birds typically possess digestive systems that can handle a broad spectrum of food types. Unlike strict carnivores with short digestive tracts optimized for protein breakdown, or herbivores with complex fermentation chambers, omnivores have intermediate gut structures. For example, the American Robin (Turdus migratorius) has a muscular gizzard capable of grinding earthworms and insects, while also efficiently processing berries and soft fruits.

Examples of Omnivorous Birds

Understanding which birds are omnivores helps clarify the misconception that all birds eat only seeds or insects. Below are several well-known omnivorous species:

- American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos): Highly intelligent and adaptable, crows eat insects, small animals, eggs, grains, fruits, and human food waste.

- Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata): Known for their striking plumage, blue jays consume acorns, seeds, fruits, insects, and occasionally nestlings of other birds. \li>Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos): Feeds on berries and fruits during winter and switches to insects and spiders in spring and summer.

- Mallard Duck (Anas platyrhynchos): Dabbling ducks often eat aquatic plants, seeds, small fish, crustaceans, and insect larvae.

- European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris): An invasive but widespread omnivore consuming fruits, seeds, suet, insects, and garbage.

These examples illustrate how omnivory enhances survival by allowing birds to exploit seasonal food availability. In early spring, when insects emerge, omnivores shift toward protein-rich prey to support breeding and chick-rearing. In autumn and winter, they rely more heavily on berries, seeds, and stored food.

Distinguishing Omnivores from Other Dietary Groups

To fully answer "is a bird an omnivore," it's essential to contrast omnivory with other dietary classifications among birds:

| Diet Type | Description | Example Species |

|---|---|---|

| Omnivore | Eats both plants and animals | Crow, Robin, Rook |

| Carnivore | Primarily eats meat (insects, fish, mammals) | Bald Eagle, Peregrine Falcon, Shrike |

| Herbivore | Consumes mostly plant material | Geese, Parrots (some), Hoatzin |

| Insectivore | Specializes in eating insects and arthropods | Swallows, Nighthawks, Wrens |

| Nectarivore | Feeds mainly on nectar | Hummingbirds, Sunbirds |

| Granivore | Eats primarily seeds | Sparrows, Finches, Pigeons |

This table highlights that while omnivory is common, it is just one of many evolutionary adaptations in avian nutrition. Some birds blur the lines between categoriesâfor instance, hummingbirds may consume small insects for protein despite being primarily nectarivorous.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Omnivorous Birds

Beyond biology, omnivorous birds hold symbolic meaning across cultures. Crows and ravens, often seen scavenging in both natural and urban settings, symbolize intelligence, transformation, and duality in mythology. In Native American traditions, the raven is a trickster figure who brings light and knowledge through cunningâtraits mirrored in its flexible, omnivorous lifestyle.

Likewise, the robin, a familiar garden omnivore, represents renewal and the arrival of spring in European folklore. Its diet of worms and berries ties it to cycles of life, death, and rebirth. Observing these birds in daily life connects people to broader ecological rhythms, reinforcing the importance of biodiversity and habitat preservation.

Practical Tips for Observing Omnivorous Birds

If you're interested in attracting or identifying omnivorous birds in your area, consider the following actionable tips:

- Provide Diverse Food Sources: Set up feeders with sunflower seeds, suet, fruit slices (like apples or oranges), and mealworms. This variety appeals to omnivores like jays, starlings, and robins.

- Create a Natural Habitat: Plant native berry-producing shrubs such as elderberry, serviceberry, or holly. Allow leaf litter to accumulate in parts of your yard to attract insects, which in turn draw insect-feeding birds.

- Offer Water: A shallow birdbath or fountain attracts birds for drinking and bathing, especially important for omnivores that move between dry seeds and moist prey.

- Avoid Pesticides: Chemical-free yards support healthy insect populations, ensuring a natural protein source for omnivorous species during breeding season.

- Observe Feeding Behavior: Watch how birds interact with food. If a bird eats both berries and snails, or cracks open seeds and then hunts ants, itâs likely omnivorous.

Timing matters too. Early morning and late afternoon are peak feeding times. During nesting season (spring to early summer), omnivorous birds increase their intake of animal matter to feed protein-hungry chicks.

Regional Differences in Avian Omnivory

The extent to which birds act as omnivores can vary by region due to climate, habitat, and food availability. In tropical regions, where fruit is abundant year-round, many omnivorous birds rely more heavily on plant material. In temperate zones, seasonal shifts drive dramatic changes in diet.

For example, the Common Blackbird (Turdus merula) in Europe consumes more earthworms in wet spring months but switches to ivy berries and hawthorn fruits in winter. Similarly, in North America, the Northern Cardinal may appear seed-focused at feeders but regularly eats insects during warmer months.

Urban environments further influence omnivory. City-dwelling birds like pigeons and gulls have expanded their diets to include human food scraps, making them de facto omnivores even if their ancestral diet was more specialized.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Diets

Several myths persist about what birds eat:

- Myth: All birds eat birdseed. Truth: Many omnivorous and insectivorous birds ignore traditional seed feeders unless alternative foods are provided.

- Myth: Omnivorous birds are less 'natural' if they eat human food. Truth: Scavenging is a natural survival strategy. Gulls and crows have always eaten carrion and refuse; urbanization simply changes the source.

- Myth: If a bird eats meat, it must be a predator. Truth: Omnivores like robins eat worms not out of predation but necessity. They lack the physical traits of true raptors, such as sharp talons and hooked beaks.

Another misconception is that omnivory implies lower specialization. On the contrary, omnivorous birds often exhibit high behavioral flexibility and cognitive complexity, enabling them to solve problems and adapt quicklyâa trait especially evident in corvids.

How Scientists Study Bird Diets

Researchers use multiple methods to determine whether a bird is truly omnivorous:

- Stomach Content Analysis: Examining undigested material in deceased birds provides direct evidence of recent meals.

- Fecal Analysis: Non-invasive method using droppings to identify plant fibers, insect exoskeletons, or seeds.

- Stable Isotope Analysis: Measures ratios of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in feathers or blood to infer long-term dietary patterns.

- Field Observation: Documenting feeding behavior in natural habitats gives context to dietary choices.

- Beak and Digestive Anatomy: Structural features offer cluesâe.g., a strong gizzard suggests seed consumption, while a slender bill may indicate insect probing.

These tools help ornithologists classify birds accurately and monitor how diets change over time due to environmental pressures like climate change or habitat loss.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all birds omnivores?

No, not all birds are omnivores. While many common species are omnivorous, others specialize in specific diets such as nectar, seeds, or meat. Diet varies widely across species.

Can a bird be both omnivore and vegetarian depending on the season?

Yes. Many omnivorous birds adjust their diets seasonally. For example, they may eat mostly insects in spring and switch to fruits and seeds in fall and winter.

Do omnivorous birds help control pests?

Yes. By consuming large quantities of insects, grubs, and slugs, omnivorous birds like robins and starlings contribute to natural pest control in gardens and agricultural areas.

What should I feed omnivorous birds in my backyard?

Offer a mix of foods: fresh fruit, unsalted peanuts, suet, mealworms, and quality seed blends. Avoid bread, which lacks nutritional value.

Is it safe for birds to eat human food scraps?

Only certain scraps are safeâplain cooked rice, vegetables, or unseasoned meat. Never give birds salty, sugary, or processed foods, which can be harmful.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4