Yes, a penguin is considered a bird, even though it cannot fly. This fact often surprises people who associate birds primarily with flight. However, in biological terms, the classification of an animal as a bird depends on specific anatomical and genetic traits—not the ability to fly. Penguins meet all the scientific criteria for avian classification: they have feathers, lay hard-shelled eggs, possess beaks, and are warm-blooded vertebrates with a high metabolic rate. A natural longtail keyword variant like 'is a penguin considered a bird despite not flying' reflects a common user query that underscores this widespread misconception. Understanding why penguins are birds requires exploring both their evolutionary biology and the defining characteristics of modern birds.

Defining What Makes a Bird a Bird

To fully grasp why penguins qualify as birds, it’s essential to understand the biological definition of the class Aves. Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates characterized by several key features: the presence of feathers, the production of hard-shelled eggs, the possession of a beak or bill with no teeth, a lightweight skeleton adapted for flight (in most species), and a highly efficient respiratory system with air sacs. While flight is common among birds, it is not a requirement for classification within Aves.

Feathers are perhaps the most distinctive trait. No other animal group possesses true feathers, which evolved from reptilian scales and serve multiple functions including insulation, display, and aerodynamics. Penguins are fully feathered, with densely packed, short, stiff feathers that provide excellent thermal insulation in cold Antarctic waters. These feathers trap a layer of air next to the skin, reducing heat loss and enhancing buoyancy—critical adaptations for a marine lifestyle.

Another defining feature is oviparity—laying eggs. All birds reproduce by laying amniotic eggs with calcified shells, and penguins are no exception. Species like the Emperor penguin incubate a single egg on the feet beneath a brood pouch during the harsh Antarctic winter, showcasing remarkable parental care strategies shared across many bird species.

Penguin Anatomy: Bird-Like Traits Beyond Feathers

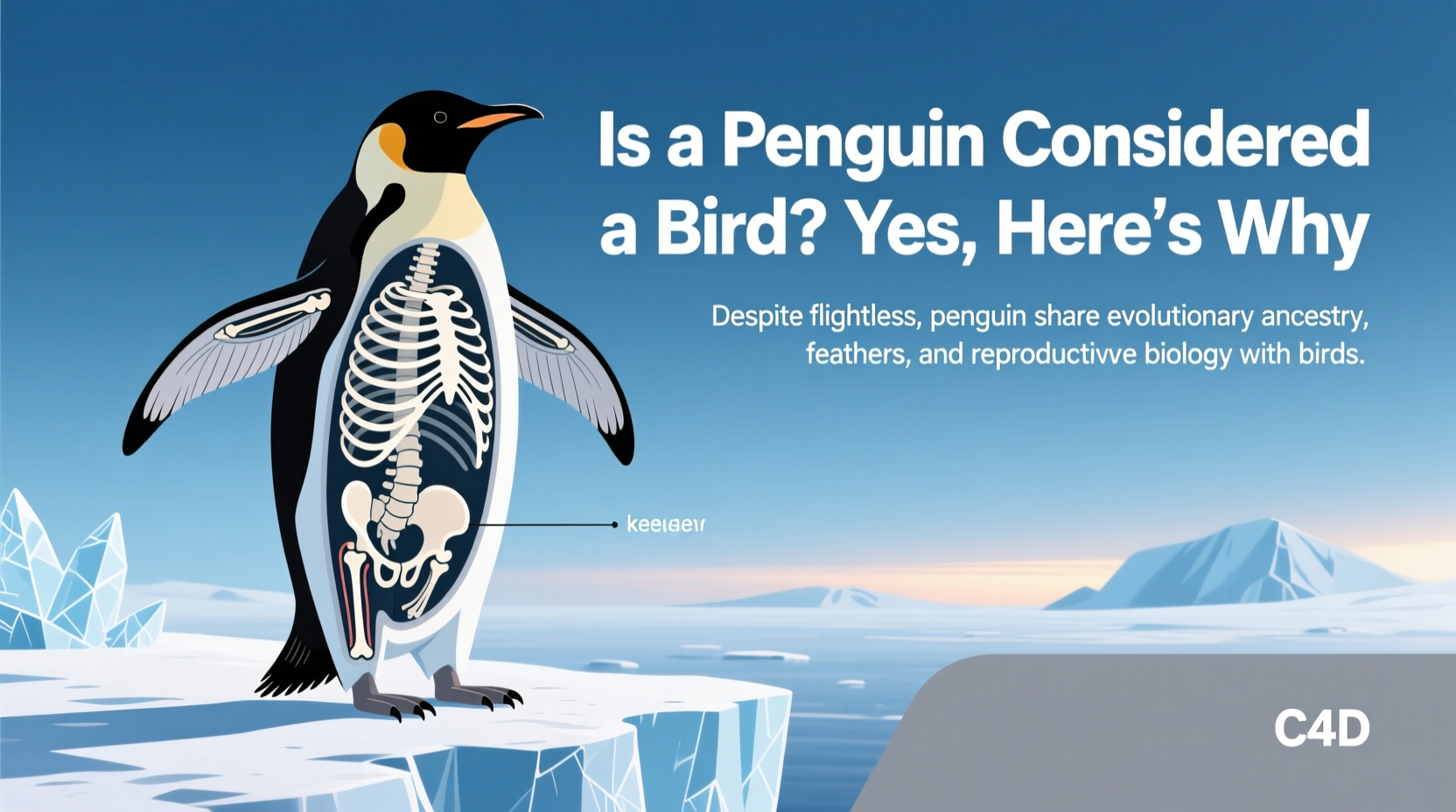

Beyond feathers and reproduction, penguins exhibit numerous avian anatomical traits. Their skeletal structure, while modified for swimming, retains core bird characteristics. For example, penguins have a fused clavicle (the furcula or 'wishbone'), a keeled sternum for muscle attachment, and a bird-specific respiratory system with air sacs that allow for efficient oxygen exchange—essential for deep diving.

Their wings, though adapted into flippers, are structurally homologous to the forelimbs of other birds and bats. The bones—the humerus, radius, ulna, and carpals—are present but shortened and flattened, optimized for propulsion underwater rather than lift in the air. This modification is an example of evolutionary adaptation, not a departure from avian status.

Penguins also possess a bird-like digestive system, complete with a crop for food storage and a gizzard to grind food, since they lack teeth. Their vision is adapted for underwater clarity, and their hearing and balance systems align closely with those of other seabirds.

Evolutionary History: How Penguins Fit into the Bird Family Tree

Penguins evolved from flying ancestors approximately 60 million years ago, shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs. Fossil evidence, such as Waimanu manneringi, reveals early penguins with longer beaks and more primitive wing structures, suggesting a gradual transition from aerial to aquatic life.

Genetic studies place penguins within the order Sphenisciformes and the family Spheniscidae. They are most closely related to Procellariiformes—the group that includes albatrosses and petrels—indicating a shared ancestor that likely lived in the Southern Hemisphere. This evolutionary lineage confirms their status as true birds, deeply embedded in the avian phylogenetic tree.

Their flightlessness is a result of adaptive evolution in isolated, predator-free environments where swimming efficiency offered greater survival advantages than flight. Over millions of years, natural selection favored individuals with stronger flippers, denser bones (to reduce buoyancy), and enhanced oxygen storage capacity—traits that make them exceptional divers but incapable of flight.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Penguins as Birds

Culturally, penguins occupy a unique space in human imagination. Often anthropomorphized in films like March of the Penguins or Mary Poppins, they symbolize resilience, loyalty, and community due to their monogamous breeding habits and cooperative huddling behavior. Indigenous cultures in the Southern Hemisphere, particularly in Patagonia and New Zealand, have oral traditions that reference penguins as sea spirits or messengers.

In conservation discourse, penguins serve as flagship species for climate change awareness. Their dependence on stable ice sheets and marine ecosystems makes them indicators of environmental health. The image of a penguin standing on melting ice has become a powerful symbol of ecological vulnerability—despite not being mammals or polar bears, they are frequently associated with Arctic imagery (a common misconception, as most penguins live in the Southern Hemisphere).

This cultural visibility sometimes blurs biological understanding. Because they walk upright, lack visible wings, and live in extreme environments, many assume penguins are mammals or evolutionary outliers. Clarifying their identity as birds helps promote accurate scientific literacy.

Observing Penguins: A Birder’s Guide

For birdwatchers, spotting penguins is a bucket-list experience. Though they don’t migrate globally like songbirds, several species can be observed in the wild across the Southern Hemisphere. Key locations include:

- Antarctica: Home to Emperor and Adélie penguins; accessible via expedition cruises (Nov–Mar).

- South Georgia Island: Hosts massive colonies of King penguins.

- Patagonia, Argentina: Punta Tombo offers easy access to Magellanic penguins.

- New Zealand: The endangered Yellow-eyed penguin can be seen on Stewart Island.

- South Africa: Boulders Beach near Cape Town hosts a thriving colony of African penguins.

Best viewing times vary by species and location, but the austral spring and summer (October to March) are generally optimal. During these months, penguins are active in nesting, courtship, and chick-rearing behaviors, offering rich observational opportunities.

When planning a trip, always check local regulations and tour operator credentials. Responsible ecotourism practices—such as maintaining distance, avoiding flash photography, and following designated paths—help protect sensitive breeding grounds.

Common Misconceptions About Penguins and Bird Classification

Several myths persist about penguins and their biological status. One of the most common is the belief that 'if it doesn’t fly, it’s not a bird.' This misunderstanding stems from informal definitions that prioritize flight over scientific criteria. Other misconceptions include:

- Penguins are mammals because they’re warm-blooded and nurse their young. False: While penguins are warm-blooded, they do not produce milk. Chicks are fed regurgitated food, not milk.

- All penguins live in Antarctica. False: Only a few species inhabit Antarctica; others thrive in temperate zones.

- Penguins can’t fly at all, so they must be different from birds. False: Flightlessness has evolved independently in multiple bird lineages (e.g., ostriches, kiwis, moas).

Understanding that birds represent a diverse class—with over 10,000 species exhibiting vast morphological variation—is crucial. From hummingbirds to ostriches, the range of size, habitat, and locomotion within Aves is extraordinary.

Comparative Table: Penguins vs. Typical Flying Birds

| Feature | Penguins | Flying Birds (e.g., Gulls) |

|---|---|---|

| Feathers | Present (dense, waterproof) | Present (lightweight, aerodynamic) |

| Flight | No (adapted for swimming) | Yes |

| Bone Density | High (reduces buoyancy) | Low (pneumatized for flight) |

| Wings | Flippers (short, rigid) | Airfoils (long, flexible) |

| Reproduction | Lays eggs, biparental care | Lays eggs, variable care |

| Habitat | Marine, Southern Hemisphere | Global, diverse |

Why the Question 'Is a Penguin Considered a Bird?' Matters

This question is more than a trivia point—it reflects broader issues in science communication and public understanding of taxonomy. In an era of rapid environmental change, accurately categorizing species informs conservation priorities, legal protections, and educational curricula. Recognizing penguins as birds underscores the importance of biodiversity within well-known animal classes.

It also highlights how evolution shapes form and function. Penguins exemplify adaptive radiation: a lineage diversifying to exploit new ecological niches. Their transformation from flying ancestors to apex marine predators demonstrates nature’s flexibility within biological constraints.

From a policy standpoint, classifying penguins correctly ensures they receive appropriate protection under wildlife laws such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (for certain species) or the Endangered Species Act. Misclassification could lead to inadequate safeguards.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Can penguins fly?

- No, penguins cannot fly in the air. Their wings have evolved into flippers for swimming. However, they are exceptionally agile 'underwater fliers,' using wing motions similar to flight to propel themselves through water.

- Are penguins mammals?

- No, penguins are not mammals. They do not have mammary glands, do not give live birth, and are covered in feathers, not hair or fur.

- What makes a penguin a bird if it can’t fly?

- Flight is not a requirement for bird classification. Penguins have feathers, lay eggs, have beaks, and share skeletal and genetic traits with other birds—all definitive avian characteristics.

- Do all penguins live in cold climates?

- No. While some species live in Antarctica, others inhabit temperate or even tropical regions. The Galápagos penguin lives near the equator, surviving through behavioral adaptations and cool ocean currents.

- How can I see penguins in the wild?

- Visit coastal regions of the Southern Hemisphere during breeding seasons. Popular sites include South Africa, Argentina, New Zealand, and sub-Antarctic islands. Always choose eco-certified tour operators to minimize impact.

In conclusion, the answer to 'is a penguin considered a bird' is unequivocally yes. Scientific evidence from anatomy, genetics, and evolution all confirm their place within the class Aves. While their appearance and lifestyle differ dramatically from songbirds or raptors, these differences reflect adaptation, not exclusion. Appreciating penguins as birds enriches our understanding of evolutionary biology and the incredible diversity of life on Earth.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4