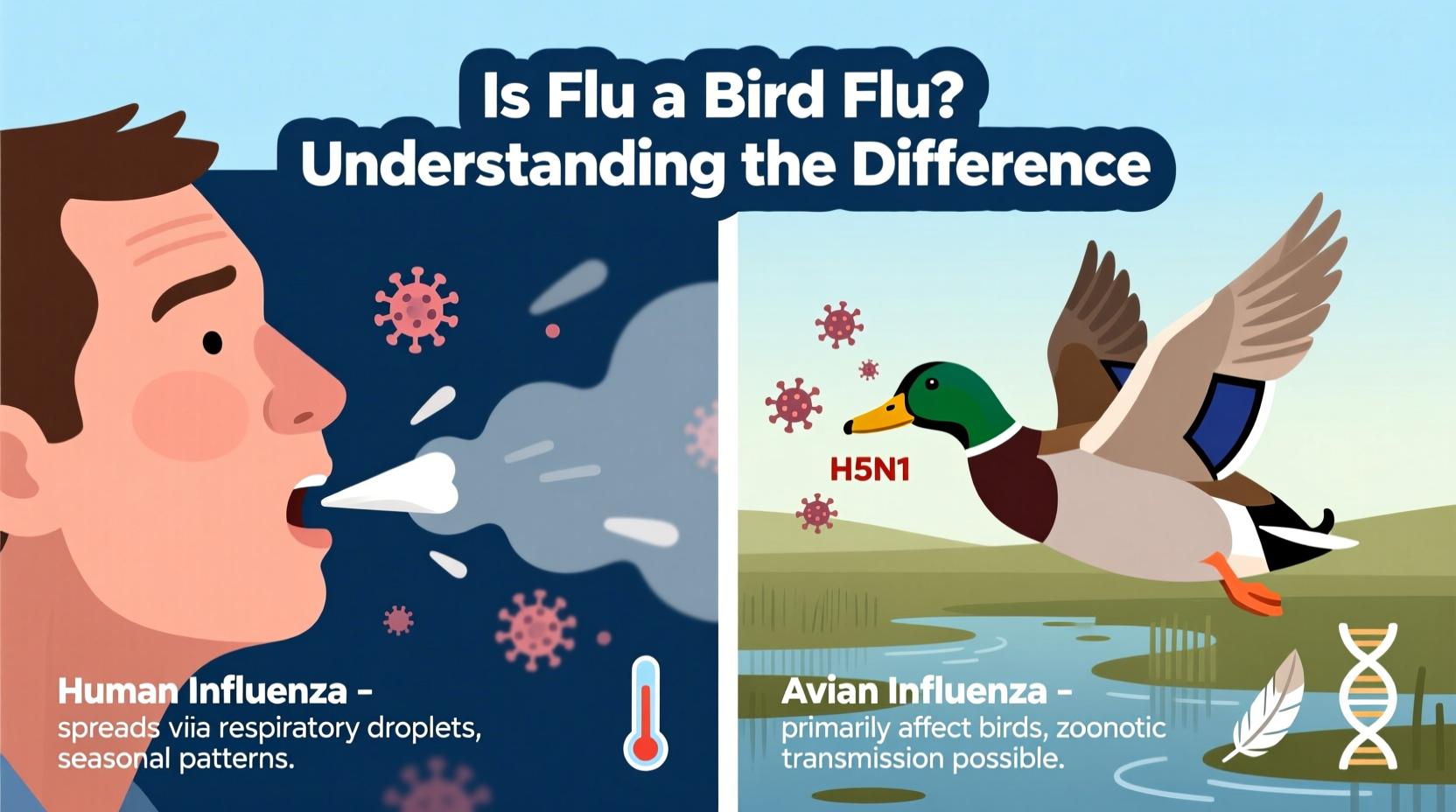

No, flu is not always bird flu. Influenza, commonly known as the flu, is a viral infection that affects humans and various animals, but only certain strains originate in birds—these are referred to as avian influenza or bird flu. The term 'bird flu' specifically describes influenza A viruses that primarily infect wild aquatic birds and can occasionally spread to domestic poultry and, in rare cases, to humans. Therefore, while all bird flu is a type of influenza, not all flu is bird flu—a crucial distinction often missed in public discourse about flu outbreaks and pandemic risks.

Understanding Influenza: Types and Origins

Influenza viruses are categorized into four types: A, B, C, and D. Among these, influenza A is the most diverse and concerning due to its ability to infect multiple species, including birds, pigs, horses, and humans. This broad host range makes it the primary source of both seasonal flu epidemics and potential pandemics. Influenza B and C mainly affect humans, with B causing seasonal outbreaks and C resulting in mild respiratory illness. Influenza D primarily affects cattle and is not known to infect humans.

Influenza A viruses are further classified by subtypes based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, leading to combinations such as H5N1, H7N9, and H1N1. While many of these circulate among birds, only specific strains pose significant threats to human health. For example, H5N1 and H7N9 are highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses that have caused sporadic human infections with high mortality rates.

Bird Flu vs. Seasonal Human Flu: Key Differences

One common misconception is equating seasonal human flu with bird flu. Seasonal flu is typically caused by human-adapted strains of influenza A (like H1N1 and H3N2) and influenza B. These viruses spread efficiently from person to person through respiratory droplets and are responsible for annual winter outbreaks worldwide.

In contrast, bird flu viruses like H5N1 do not easily transmit between humans. Most human cases occur after direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments—such as live bird markets or farms experiencing outbreaks. When human-to-human transmission does occur, it’s usually limited and inefficient. However, scientists remain vigilant because if a bird flu virus mutates to become easily transmissible among people, it could trigger a global pandemic.

| Virus Type | Primary Hosts | Human Transmission | Pandemic Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza A (H1N1) | Humans, pigs | High (seasonal) | Moderate |

| Influenza A (H5N1) | Birds (especially waterfowl) | Rare, limited | High if mutation occurs |

| Influenza B | Humans only | High (seasonal) | Low |

| Influenza A (H7N9) | Birds (poultry) | Occasional spillover | Medium-High |

Historical Context: Major Bird Flu Outbreaks

The first documented case of human infection with an avian influenza virus was H5N1 in Hong Kong in 1997. That outbreak led to six deaths out of 18 confirmed cases and prompted the culling of 1.5 million chickens to contain the spread. Since then, H5N1 has become endemic in some bird populations across Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe.

A significant resurgence occurred in 2003–2004, when H5N1 spread rapidly across Southeast Asia, affecting both poultry industries and public health systems. More recently, during 2021–2023, a new clade of H5N1 (clade 2.3.4.4b) emerged and spread globally via migratory birds, reaching North America and causing massive die-offs in wild bird populations and commercial poultry flocks.

Another notable strain, H7N9, appeared in China in 2013. Unlike H5N1, which causes severe disease in birds, H7N9 is low pathogenic in poultry, making detection harder. Yet, it proved deadly in humans, with a case fatality rate exceeding 30%. These historical patterns underscore how changes in farming practices, global trade, and climate-driven bird migration influence the emergence and spread of bird flu.

How Bird Flu Spreads: Ecology and Transmission Pathways

Wild aquatic birds—particularly ducks, geese, and shorebirds—are natural reservoirs for avian influenza viruses. They carry the virus in their intestines and shed it through feces, saliva, and nasal secretions. While they often show no symptoms, the virus can persist in water and soil, posing a risk to domestic poultry.

Transmission to humans usually happens in settings where there is close contact with infected birds. High-risk environments include backyard farms, live animal markets, and areas involved in poultry slaughter or processing. Workers without proper protective equipment are especially vulnerable.

There is also growing concern about indirect transmission. Contaminated vehicles, clothing, feed, or even footwear can carry the virus between farms. Additionally, migratory birds play a critical role in spreading the virus across continents, particularly along flyways used during seasonal migrations.

Symptoms and Diagnosis in Humans and Birds

In birds, symptoms of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) can include sudden death, lack of energy, decreased egg production, swelling of the head, and difficulty breathing. Some birds may die before showing any signs. Rapid diagnostic tests and laboratory analysis (such as PCR testing) are essential for confirming outbreaks.

In humans, bird flu symptoms resemble those of severe influenza: high fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and malaise. However, progression can be rapid, leading to pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multi-organ failure. Early diagnosis is challenging because initial symptoms mimic common flu, but travel history or exposure to sick birds provides key clues.

If bird flu is suspected, healthcare providers should collect respiratory samples for specialized testing at public health laboratories. Prompt antiviral treatment with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or zanamivir may improve outcomes, especially if administered within 48 hours of symptom onset.

Prevention and Control Measures

Preventing bird flu outbreaks requires coordinated efforts at local, national, and international levels. For poultry farmers, biosecurity is paramount. This includes restricting access to bird enclosures, disinfecting equipment, preventing contact between wild and domestic birds, and monitoring flocks for signs of illness.

Government agencies often implement surveillance programs to detect avian influenza early. In outbreak zones, mass culling of infected or exposed birds may be necessary to prevent further spread. Vaccination of poultry is used in some countries, though it presents challenges such as masking infection and complicating surveillance.

For travelers visiting regions with active bird flu outbreaks, the CDC recommends avoiding poultry farms, live bird markets, and surfaces contaminated with bird droppings. Practicing good hand hygiene and wearing masks in high-risk areas can reduce exposure risk.

Public Health Implications and Pandemic Preparedness

Bird flu remains one of the top concerns for global pandemic preparedness. Because humans generally lack immunity to novel avian influenza strains, a virus that gains efficient human-to-human transmission could spread rapidly. The World Health Organization (WHO) maintains a Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) to monitor emerging strains and support vaccine development.

Pandemic planning includes stockpiling antiviral drugs, developing candidate vaccine viruses, and enhancing laboratory capacity. Public communication strategies aim to reduce panic while promoting informed behavior during outbreaks.

Recent advances in genomic sequencing allow scientists to track mutations in real time. Of particular concern is reassortment—the process by which different influenza viruses exchange genetic material inside a co-infected host (e.g., a pig or human). Such events could produce a hybrid virus with both high transmissibility and virulence.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about bird flu. One is that eating properly cooked poultry or eggs can transmit the virus. According to the USDA and WHO, this is false; cooking food to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) kills the virus. Another myth is that pet birds are major sources of infection. While possible, household pets like parrots or canaries are unlikely to contract or spread HPAI unless exposed to infected wild birds.

Some believe bird flu is just another name for seasonal flu. As established, this is incorrect. Seasonal flu circulates annually among humans and is predictable in terms of immunity and vaccine design. Bird flu, in contrast, represents zoonotic spillover events with unpredictable consequences.

Current Status and Monitoring Efforts

As of 2024, H5N1 continues to circulate globally, with outbreaks reported in wild birds and commercial poultry in over 50 countries. In the United States, the USDA and CDC collaborate on monitoring through the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHLN) and interagency task forces.

Cases in dairy cattle were detected in 2024, marking a new transmission pathway and raising concerns about mammalian adaptation. A few human cases linked to farm exposure have been reported, reinforcing the need for vigilance in agricultural sectors.

Global organizations like the FAO, OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health), and WHO issue regular updates and risk assessments. Citizens can stay informed through official health department websites and avoid relying solely on social media rumors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can bird flu spread from human to human? Currently, bird flu does not spread easily between people. Most cases result from direct bird contact. Sustained human-to-human transmission has not been observed.

- Is it safe to eat chicken and eggs during a bird flu outbreak? Yes, as long as they are properly handled and cooked to recommended temperatures. The virus is destroyed by heat.

- Are there vaccines for bird flu in humans? There are no commercially available vaccines for the general public, but candidate vaccines exist for stockpiling in case of a pandemic.

- What should I do if I find a dead wild bird? Do not touch it. Report it to your local wildlife or health authority for testing, especially if multiple birds are found dead.

- How is bird flu different from swine flu? Swine flu (e.g., H1N1) originates in pigs and spreads more easily among humans. Bird flu comes from birds and rarely transmits between people.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4