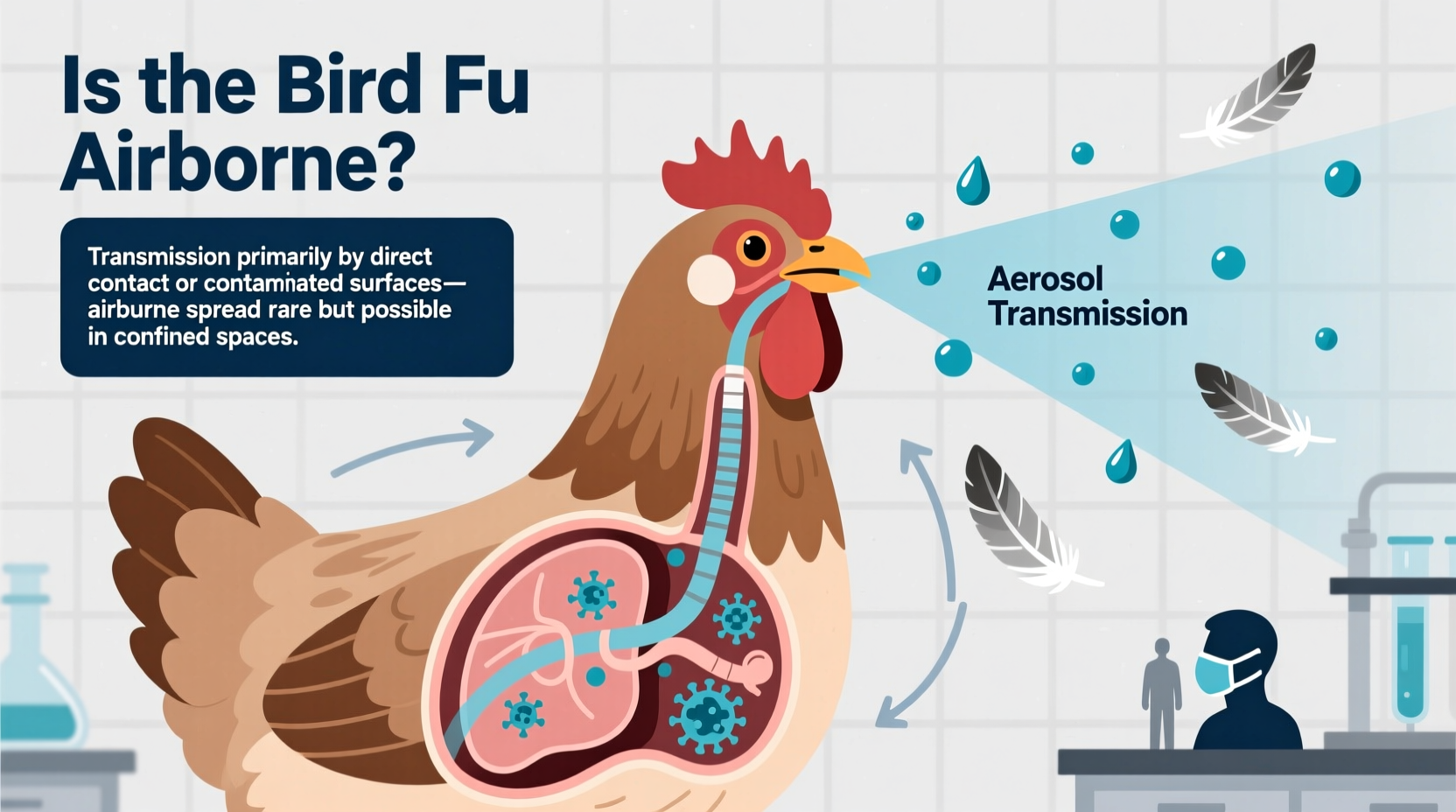

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, is primarily not considered airborne in the same way that human influenza or COVID-19 spreads through fine aerosol particles over long distances. However, recent scientific evidence suggests that under certain conditions—particularly in enclosed, poorly ventilated spaces such as poultry farms—the virus can become airborne via respiratory droplets and contaminated dust, allowing transmission over short distances between birds and potentially to humans in close contact. This distinction is critical for both public health planning and bird conservation efforts, especially when assessing risks during outbreaks. Understanding whether the bird flu is airborne helps guide safety protocols for farmers, veterinarians, wildlife biologists, and even backyard bird enthusiasts.

What Is Bird Flu?

Bird flu refers to a group of influenza viruses that primarily infect birds. These viruses belong to the Influenzavirus A family and are naturally hosted by wild aquatic birds like ducks, geese, and shorebirds, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms. There are numerous subtypes based on surface proteins—most notably H5 and H7 strains—some of which have high pathogenicity (HPAI), meaning they cause severe disease and high mortality rates in domestic poultry.

The most concerning strain in recent years has been H5N1, first identified in 1996 in China. Since then, it has evolved into multiple clades and spread globally, affecting millions of birds and occasionally jumping to mammals, including humans. While human cases remain rare, the potential for mutation and increased transmissibility keeps global health organizations vigilant.

How Does Bird Flu Spread? The Role of Airborne Transmission

To understand if bird flu is airborne, we must distinguish between different modes of transmission:

- Direct contact: Touching infected birds or their secretions (saliva, nasal mucus, feces).

- Fomite transmission: Contact with contaminated surfaces like cages, feeders, or clothing.

- Airborne transmission: Inhalation of virus-laden particles suspended in the air.

In open environments, bird flu does not travel far through the air. Unlike measles or tuberculosis, which can linger in aerosols for hours, avian influenza viruses typically spread through larger respiratory droplets that fall within a few feet. However, studies conducted in confined settings—such as commercial poultry barns—have shown that the virus can be carried in dust and feather debris, becoming aerosolized and inhaled by nearby birds or workers.

A 2022 study published in Nature Communications demonstrated that H5N1 could remain infectious in airborne particulates collected from infected turkey facilities. This supports the idea that while bird flu isn’t efficiently airborne in outdoor or well-ventilated areas, it can exhibit limited airborne behavior indoors.

Biological Factors Influencing Airborne Risk

Several biological and environmental factors influence whether bird flu becomes airborne:

- Virus strain: Highly pathogenic strains like H5N1 are more likely to generate high viral loads in infected birds, increasing shedding and potential aerosolization.

- Bird density: Crowded conditions in factory farms increase the concentration of virus particles in the air.

- Ventilation: Poor airflow traps contaminated dust and droplets, enhancing inhalation risk.

- Bird species: Waterfowl tend to excrete the virus in feces, whereas gallinaceous birds (like chickens) shed more through respiratory routes, influencing transmission dynamics.

These variables explain why outbreaks in industrial poultry operations pose higher airborne risks than those observed in wild bird populations.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds During Pandemics

Birds have long held symbolic roles across cultures—as messengers, omens, and spiritual guides. In times of disease outbreaks, these meanings often shift. For example, crows and ravens, traditionally seen as intelligent and adaptive, may be stigmatized during bird flu scares due to fears of contagion. Similarly, doves, symbols of peace, might evoke anxiety if found sick or dead in urban parks.

This cultural tension underscores the need for science communication that respects symbolic values while promoting biosecurity. Public messaging should avoid vilifying birds; instead, emphasize responsible coexistence and monitoring. After all, wild birds play essential ecological roles in seed dispersal, pest control, and nutrient cycling.

Implications for Human Health: Can People Get Infected Through the Air?

Human infections with bird flu remain rare but serious. Most cases result from direct exposure to sick or dead poultry, especially in live bird markets or rural farms. However, there is growing concern about occupational airborne exposure.

Workers in poultry processing plants, veterinarians, and cullers involved in outbreak responses face elevated risks. Protective measures—including N95 respirators, eye protection, and strict decontamination procedures—are recommended in high-risk zones. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises against using simple surgical masks in such settings because they do not filter fine airborne particles effectively.

While sustained human-to-human transmission has not occurred, any indication of respiratory-based spread in mammals raises red flags. In 2023, an H5N1 outbreak among mink in Spain showed signs of possible airborne transmission between animals, suggesting the virus may be adapting to new hosts—a development closely monitored by virologists.

Wildlife Conservation and Avian Influenza Monitoring

For ornithologists and conservationists, bird flu presents a dual challenge: protecting vulnerable bird species and preventing spillover into domestic systems. Some endangered birds, such as the California condor and whooping crane, are particularly susceptible due to small population sizes and limited genetic diversity.

Agencies like the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) run surveillance programs tracking migratory patterns and testing dead birds. When clusters of mortality appear—especially in raptors, seabirds, or waterfowl—rapid response teams are deployed to contain spread.

Interestingly, some bird species show resistance. Mallards, for instance, often carry low levels of the virus asymptomatically, acting as reservoirs. Understanding this variation helps scientists predict hotspots and design targeted interventions.

Practical Guidance for Birdwatchers and Backyard Bird Feeders

If you enjoy observing birds, you may wonder: should I stop feeding birds during a bird flu outbreak? The answer depends on your location and local guidelines.

In regions experiencing active HPAI outbreaks, wildlife agencies often recommend temporarily removing bird feeders and baths to reduce congregation and cross-contamination. Here’s what you can do:

- Check local advisories: Visit websites like the CDC, USGS National Wildlife Health Center, or your state’s Department of Natural Resources.

- Clean feeders regularly: If you continue feeding, disinfect feeders weekly with a 10% bleach solution.

- Avoid handling sick or dead birds: Use gloves and report findings to authorities.

- Keep pets away: Dogs and cats may pick up the virus from carcasses and transmit it to humans.

During migration seasons (spring and fall), heightened vigilance is crucial, as infected birds may enter new areas.

Regional Differences in Outbreak Management

Policies vary significantly by country and region. In the European Union, strict biosecurity measures are enforced on farms, including mandatory indoor housing of poultry during outbreak periods. In contrast, the United States relies more on voluntary compliance and regional zoning.

In Asia, where live bird markets are common, transmission risks are higher. Countries like Vietnam and Indonesia have implemented periodic market closures and vaccination campaigns. However, vaccine use in poultry is controversial—it can reduce symptoms but not always prevent infection or shedding, potentially masking spread.

These differences affect how airborne risks are managed. Enclosed markets with poor ventilation create ideal conditions for limited airborne transmission, making regulatory oversight vital.

Debunking Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Myth 1: 'Bird flu spreads easily through the air like colds.'

False. It requires close proximity and specific conditions to become airborne. Outdoor transmission via air is extremely unlikely.

Myth 2: 'Eating poultry or eggs can give you bird flu.'

No—if meat and eggs are properly cooked (to an internal temperature of 165°F / 74°C), the virus is destroyed. The main risk comes from handling live or dead infected birds.

Myth 3: 'Only wild birds carry the virus.'

Incorrect. While wild birds introduce the virus, domestic poultry flocks experience the most severe outbreaks due to crowding and susceptibility.

| Transmission Mode | Likelihood | Prevention Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Direct contact with infected birds | Very High | Wear gloves, avoid touching sick/dead birds |

| Contaminated surfaces (fomites) | High | Disinfect equipment, wash hands frequently |

| Airborne (indoor, confined spaces) | Moderate | Use N95 masks, improve ventilation |

| Airborne (outdoor, open spaces) | Very Low | No special precautions needed |

| Consuming cooked poultry/eggs | Negligible | Cook thoroughly; no risk if properly prepared |

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Scientists are actively studying whether bird flu could evolve to become more efficiently airborne among mammals, including humans. Key research focuses include:

- Genetic sequencing of circulating strains to detect mutations linked to respiratory transmission.

- Aerosol sampling in poultry facilities to quantify viral load in air.

- Vaccine development for both birds and at-risk human populations.

Early detection remains our best defense. Citizen science initiatives like eBird and iNaturalist now encourage users to report unusual bird deaths, helping track outbreaks in real time.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can bird flu spread through the air between humans?

- No confirmed cases of sustained human-to-human airborne transmission exist. Rare instances involve close, prolonged contact, but the virus does not currently spread efficiently among people.

- Should I wear a mask while birdwatching?

- Generally, no. Masks are unnecessary outdoors unless you're in a closed poultry facility or handling sick birds. Standard hygiene practices are sufficient for casual observation.

- Are migratory birds responsible for spreading bird flu globally?

- Yes, wild migratory birds—especially waterfowl—are primary carriers. They transport the virus along flyways, introducing it to new regions, though usually without mass die-offs.

- Can pets get bird flu from dead birds?

- Dogs and cats can contract the virus by chewing on infected carcasses. Keep pets leashed in areas with reported outbreaks and dispose of dead birds safely.

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

- A pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine exists in stockpiles for emergency use, but it's not available to the general public. Seasonal flu vaccines do not protect against avian influenza.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4