The phrase 'is the bird the word' may sound whimsical or metaphorical, but when interpreted through the lens of ornithology and cultural symbolism, it reveals a profound truth: birds are indeed a universal language. While birds are not mammalsâthey are warm-blooded vertebrates with feathers, beaks, and lay hard-shelled eggsâthis distinction is central to understanding what makes avian life so unique. The expression 'is the bird the word' captures how birds transcend biological classification to become symbols, messengers, and muses across human cultures. From ancient mythology to modern conservation efforts, birds speak without words, communicating through song, flight, and presence. This article explores both the scientific reality behind whether birds are mammals and the deeper cultural resonance of avian symbolism, blending biology with meaning in a way that answers not just a literal question, but an existential one.

Understanding Bird Classification: Why Birds Are Not Mammals

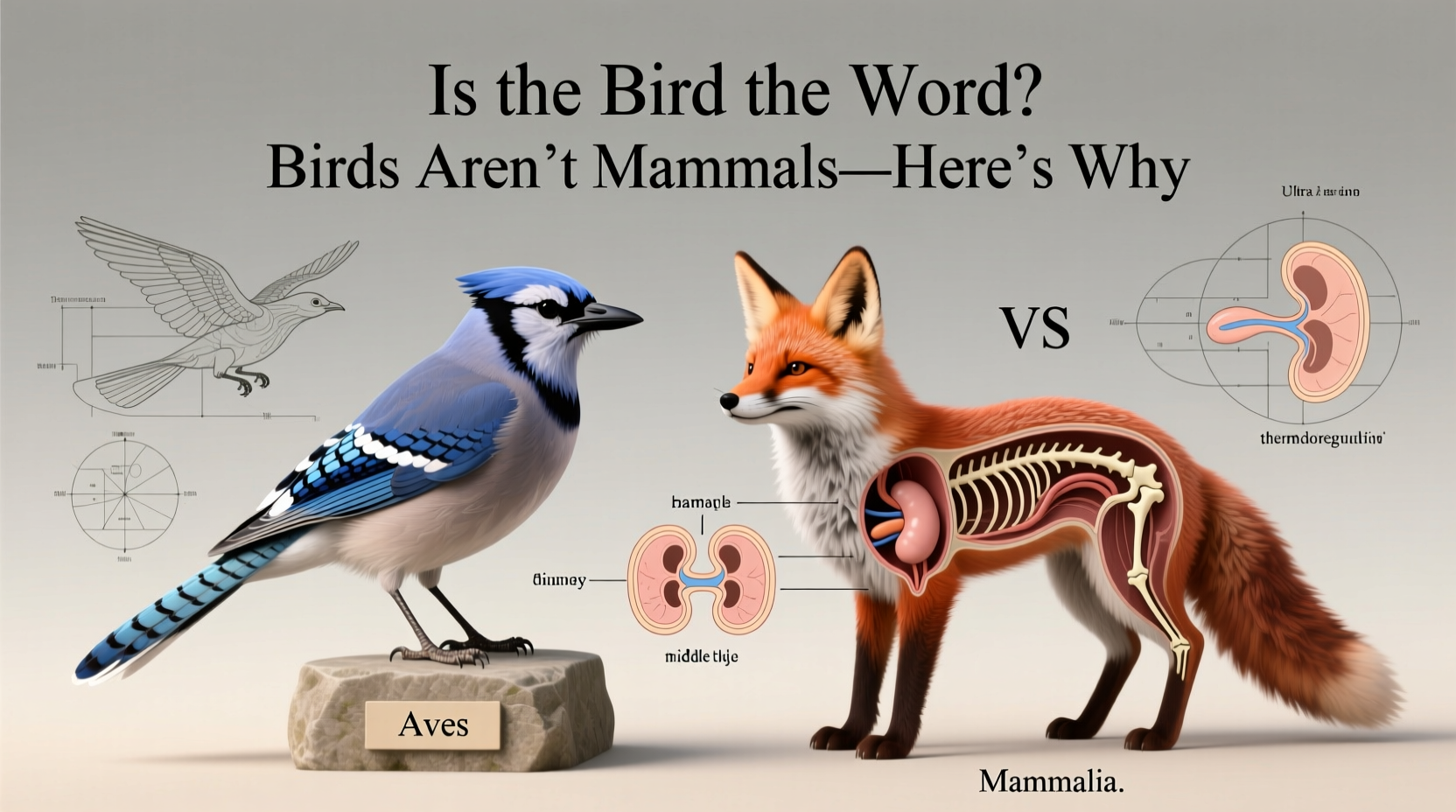

One of the most frequently asked questions in basic zoology is: Are birds mammals? The clear answer is no. Despite sharing key traits such as being warm-blooded (endothermic) and caring for their young, birds belong to a separate class of animals known as Aves, while mammals fall under the class Mammalia. These two groups diverged evolutionarily over 300 million years ago.

Birds possess several defining characteristics that set them apart:

- Feathers: Only birds have true feathers, which evolved from reptilian scales and are essential for flight and insulation.

- Beaks and Lack of Teeth: Modern birds lack teeth and use beaks adapted to their dietâwhether cracking seeds, sipping nectar, or tearing flesh.

- Egg-Laying (Oviparity): All birds reproduce by laying hard-shelled eggs, unlike most mammals, which give birth to live young (except monotremes like the platypus). \li>Skeleton and Respiration: Birds have lightweight, hollow bones and a highly efficient respiratory system with air sacs that allow continuous airflowâcritical for sustained flight.

Mammals, on the other hand, are defined by features such as hair or fur, mammary glands that produce milk, and typically giving birth to live offspring. So while a robin and a rabbit may both be warm-blooded and nurture their young, they are fundamentally different in anatomy, genetics, and evolutionary lineage.

The Evolutionary Origins of Birds: From Dinosaurs to Modern Avians

To understand why birds aren't mammals, we must look back to their origins. Fossil evidence overwhelmingly supports the theory that birds evolved from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, approximately 150 million years ago. The discovery of Archaeopteryx in the 19th century provided a crucial transitional fossilâresembling a dinosaur with wings and feathers, capable of gliding if not full flight.

Over millions of years, these proto-birds developed adaptations for powered flight: fused clavicles (forming the wishbone), keeled sternums for muscle attachment, and asymmetrical flight feathers. By the Cretaceous period, true birds had diversified alongside pterosaurs and early mammals. When the mass extinction event wiped out non-avian dinosaurs about 66 million years ago, birds were among the few survivorsâeventually radiating into over 10,000 species today.

This dinosaur ancestry explains many avian traits absent in mammals: feathers, egg-laying, and even aspects of behavior such as nesting and courtship displays. It also underscores that birds are not primitive, but rather highly specialized descendants of one of Earthâs most successful lineages.

Cultural Symbolism: Is the Bird Truly the Word?

Beyond biology, the idea that 'the bird is the word' resonates deeply in human culture. Across civilizations, birds have served as symbols of freedom, divinity, transformation, and communication. In this sense, birds do function as a kind of universal languageâa shared symbolic vocabulary understood across time and geography.

In ancient Egypt, the Baâdepicted as a human-headed birdârepresented the soul's ability to travel between worlds after death. In Greek mythology, eagles were associated with Zeus, carrying his thunderbolts and serving as omens. Native American traditions often view ravens and crows as tricksters and creators, embodying wisdom and change. In Christianity, the dove symbolizes the Holy Spirit, peace, and renewal.

Even in modern media, birds carry symbolic weight. The phoenix represents rebirth; the albatross, burden or fate; the swallow, return and homecoming. The phrase 'is the bird the word' thus taps into this archetypal role: birds as messengers between realms, interpreters of the unseen, and reflections of our deepest hopes and fears.

Practical Ornithology: How to Observe and Identify Birds

For those inspired by both the science and symbolism of birds, birdwatching (or birding) offers a tangible way to connect with avian life. Whether you're a beginner or experienced observer, here are practical steps to enhance your experience:

- Start with Local Species: Use field guides or apps like Merlin Bird ID or eBird to learn common birds in your region. Pay attention to size, shape, color patterns, beak type, and behavior.

- Choose the Right Equipment: Binoculars with 8x42 magnification are ideal for most birding. A spotting scope can help with distant waterfowl or raptors. Wear neutral-colored clothing to avoid startling birds.

- Visit Key Habitats: Different birds thrive in different environments. Woodlands attract warblers and woodpeckers; wetlands host herons, ducks, and rails; open fields may reveal hawks or meadowlarks.

- Listen to Calls and Songs: Many birds are heard before theyâre seen. Learning common songsâlike the chickadeeâs âfee-beeâ or the cardinalâs whistled phrasesâcan dramatically improve identification.

- Keep a Journal: Record species, dates, locations, weather, and behaviors. Over time, this builds a personal record of seasonal patterns and migration trends.

Timing matters too. Early morning hours (dawn to mid-morning) are typically best for bird activity, especially during spring and fall migrations. Winter birding can reveal hardy residents like finches and sparrows, while summer brings breeding plumage and territorial calls.

Migration Patterns and Seasonal Behavior

One of the most awe-inspiring aspects of bird life is migrationâthe long-distance movement between breeding and wintering grounds. Some species, like the Arctic Tern, travel over 40,000 miles annually from pole to pole. Others, such as the Bar-tailed Godwit, fly nonstop for days across oceans.

Migration is driven by changes in daylight, food availability, and temperature. Understanding these patterns helps birders anticipate arrivals and departures. For example:

| Bird Species | Migration Route | Best Observation Times |

|---|---|---|

| Ruby-throated Hummingbird | Eastern North America â Central America | AprilâMay (northbound), AugustâSeptember (southbound) |

| Swainsonâs Hawk | Western U.S./Canada â Argentina | MarchâApril, SeptemberâOctober |

| Blackpoll Warbler | Alaska/Canada â Caribbean/South America | May, late SeptemberâOctober |

To stay updated on migration timing, consult resources like the Cornell Lab of Ornithologyâs BirdCast, which uses radar data to predict nightly movements. Participating in citizen science projects like the Great Backyard Bird Count or Christmas Bird Count also contributes valuable data while deepening engagement.

Conservation Challenges Facing Birds Today

Despite their adaptability, birds face growing threats. Habitat loss, climate change, pesticide use, and window collisions kill billions annually. The 2019 study published in Science found that North America has lost nearly 3 billion birds since 1970âa staggering decline affecting even common species.

You can help by taking action:

- Make windows safer with decals or tape strips spaced closely together.

- Keep cats indoorsâfree-roaming felines kill hundreds of millions of birds each year in the U.S. alone.

- Plant native vegetation to support insects, which feed many bird species.

- Avoid pesticides and herbicides that reduce food sources.

- Support organizations like Audubon, BirdLife International, or local wildlife refuges.

Policy-level changes also matter. Advocating for protected areas, sustainable agriculture, and clean energy reduces broader environmental pressures.

Common Misconceptions About Birds

Several myths persist about birds, often blurring the line between fact and folklore:

- Myth: All birds can fly.

Truth: Flightless birds include ostriches, emus, kiwis, and penguinsâeach adapted to specific ecological niches. - Myth: Birds abandon chicks if touched by humans.

Truth: Most birds have a poor sense of smell and will not reject offspring due to human scent. However, unnecessary handling should still be avoided. - Myth: Birdseed is always beneficial.

Truth: Cheap mixes with filler grains (like milo) go uneaten and attract rodents. Opt for black oil sunflower seeds or nyjer for finches.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are birds mammals?

- No, birds are not mammals. They are classified separately in the animal kingdom based on feathers, egg-laying, and skeletal structure.

- Why do people say 'is the bird the word'?

- The phrase blends pop culture (from a 1970s cartoon theme song) with symbolic ideasâsuggesting birds represent deeper truths about nature, freedom, and communication.

- Can any birds lactate like mammals?

- No bird produces milk, though some pigeons and flamingos secrete a nutritious 'crop milk' to feed their youngâa convergent evolutionary trait, not true lactation.

- Whatâs the closest living relative to birds?

- Modern birds are most closely related to crocodilians (alligators and crocodiles), sharing a common ancestor among ancient archosaurs.

- How can I tell if a bird is a juvenile or adult?

- Juveniles often have duller plumage, shorter tails, and may beg for food. Specific field marks vary by speciesâconsult a regional guide for details.

In conclusion, while birds are definitively not mammals, they occupy a singular place in both the natural world and the human imagination. The phrase 'is the bird the word' invites us to listenânot just to songs in the trees, but to what birds symbolize: connection, resilience, and the enduring mystery of life in flight.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4