Bird beaks are made primarily of keratin, the same tough, fibrous protein that forms human fingernails, hair, and animal hooves. This lightweight yet durable material covers a bony core, which extends from the skull and gives the beak its shape and strength. The outer layer, known as the rhamphotheca, is composed of keratinized cells that continuously grow and wear down, ensuring the beak remains functional throughout a bird’s life. Understanding what bird beaks are made of reveals not only their biological efficiency but also their remarkable adaptability across species and environments.

Anatomy of a Bird Beak: Structure and Composition

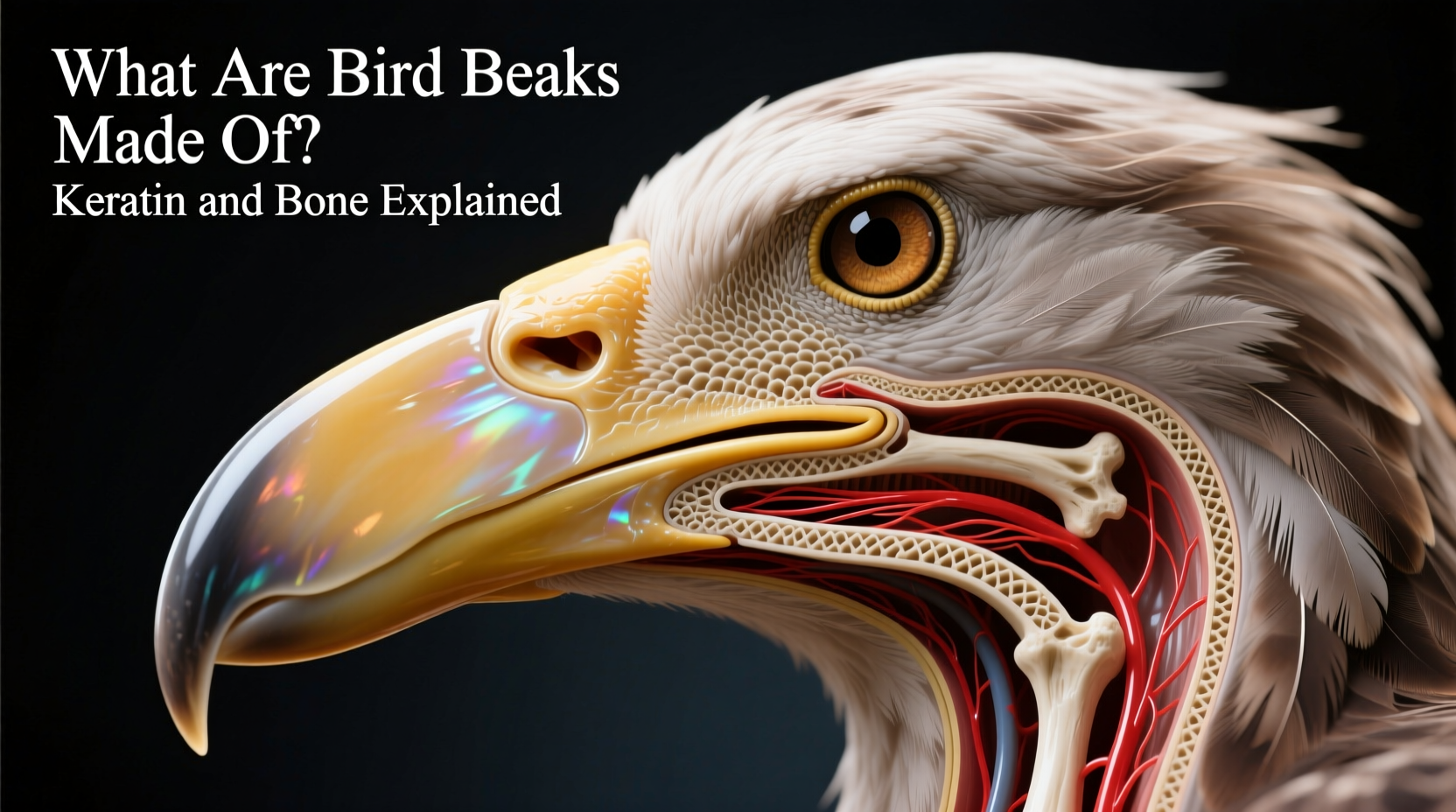

The avian beak is a highly specialized structure evolved for feeding, grooming, defense, courtship, and even thermoregulation. At its foundation lies the premaxillary and mandibular bones—the upper and lower jaw components—derived from the skull. These bones form the internal scaffold over which the keratin sheath develops.

The visible part of the beak—the rhamphotheca—is divided into two sections: the rhinotheca (upper) and the gnathotheca (lower). These layers consist of multiple strata of keratin, including the alpha-keratin found in mammals and the harder beta-keratin unique to reptiles and birds. Beta-keratin provides exceptional resistance to mechanical stress, allowing beaks to crack seeds, tear flesh, or probe delicate flowers without fracturing.

Unlike teeth, which are rooted in sockets and composed of enamel and dentin, beaks lack nerves and blood vessels in their outer keratin layer. However, the underlying bone is richly innervated, enabling birds to sense pressure, texture, and temperature while using their beaks with precision.

Keratin Growth and Beak Maintenance

One key feature of bird beaks is their continuous growth. Just as our nails lengthen over time, so too does the keratin layer on a bird's beak. In the wild, natural behaviors such as chewing, pecking, and rubbing against surfaces keep the beak properly worn and shaped. For example, parrots often chew wood to prevent overgrowth, while finches grind their beaks together after meals.

In captivity, improper diet or lack of stimulation can lead to abnormal beak growth, a condition known as beak malocclusion. Avian veterinarians may need to trim excessively long beaks, but regular access to safe chewing materials like cuttlebone, mineral blocks, or untreated wood perches helps maintain healthy wear.

Nutrition plays a critical role in keratin quality. Deficiencies in vitamin A, calcium, or protein can result in soft, brittle, or deformed beaks. Birds fed seed-only diets are especially prone to these issues, underscoring the importance of balanced nutrition tailored to species-specific needs.

Evolutionary Adaptations: How Beak Shape Reflects Function

Bird beaks exhibit extraordinary diversity due to evolutionary adaptation. Each species’ beak reflects its ecological niche and dietary preferences. This concept was famously illustrated by Charles Darwin during his study of Galápagos finches, where he observed how slight variations in beak size and shape correlated with different food sources.

Consider the following examples:

- Hawks and eagles have strong, hooked beaks made of dense keratin for tearing meat.

- Hummingbirds possess long, slender beaks adapted for reaching nectar deep within tubular flowers.

- Pelicans use large, flexible beaks with expandable pouches to scoop fish from water.

- Woodpeckers have chisel-like beaks reinforced with shock-absorbing structures to withstand repeated impact against tree bark.

These adaptations demonstrate how the fundamental composition—keratin over bone—can be modified through evolution to serve vastly different purposes. Even coloration serves functions: bright hues in toucans may play roles in mating displays or heat dissipation.

| Bird Species | Beak Type | Primary Function | Material Composition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bald Eagle | Hooked | Tearing prey | Keratin sheath over fused maxillary bones |

| Northern Cardinal | Short, conical | Cracking seeds | Hard beta-keratin with rapid wear rate |

| Sandalwood Finch | Long, curved | Extracting insects | Flexible keratin with high tensile strength |

| Flamingo | Downward-bent, filter-feeding | Straining algae and shrimp | Keratin-lined plates (lamellae) |

| Kiwi | Long, sensitive tip | Probing soil for worms | Soft-tipped keratin with sensory pits |

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Bird Beaks

Beyond biology, bird beaks hold symbolic meaning across cultures. In ancient Egypt, the god Thoth was depicted with the head of an ibis, whose long, curved beak symbolized wisdom and divine measurement. Similarly, Native American traditions often associate sharp-beaked raptors like eagles with vision, authority, and spiritual messages.

In literature and art, the precision of a bird’s beak represents clarity and focus. Poets have likened it to a needle stitching sky to earth, emphasizing its dual role as tool and conduit between realms. Even modern idioms—such as “clean bill of health,” derived from the appearance of a healthy beak—reflect how deeply embedded avian traits are in human expression.

Understanding what bird beaks are made of enhances appreciation not just of their physical design but also of their metaphorical power. Their construction from keratin—a substance both humble and resilient—mirrors themes of endurance and transformation found in myths worldwide.

Observing Beaks in the Wild: Tips for Birdwatchers

For amateur and experienced birdwatchers alike, beak morphology offers crucial clues for identification and behavioral interpretation. When observing birds in nature, consider the following practical tips:

- Use binoculars with close-focus capability: Many small birds feed at close range, and detailed views reveal subtle textures and colors in the keratin sheath.

- Note feeding behavior: Watch how a bird uses its beak—is it probing mud, cracking nuts, or skimming water? Behavior often confirms taxonomic guesses based on shape.

- Photograph for later analysis: High-resolution images allow you to examine beak structure more closely and compare with field guides.

- Listen for sounds: Some birds drum with their beaks (like woodpeckers), while others snap them during courtship displays.

- Respect distance: Avoid disturbing nesting or feeding birds; use blinds or quiet observation points when possible.

Regional field guides often include illustrations highlighting beak differences among similar species. For instance, distinguishing between warblers or sparrows frequently depends on minute details like culmen curvature or gape width—all features tied to the underlying keratin architecture.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Beaks

Despite widespread fascination, several misconceptions persist about bird beaks:

- Misconception: Beaks are made of bone. Correction: While supported by bone internally, the visible portion is entirely keratin—a common confusion due to the rigid feel of some beaks.

- Misconception: Birds can regrow entire beaks if broken. Correction: Minor damage may heal as keratin regenerates, but severe fractures involving the bony core can be fatal or require veterinary intervention.

- Misconception: All beaks are hard. Correction: Some species, like kiwis, have soft, flexible tips packed with sensory receptors for detecting prey underground.

- Misconception: Color indicates age only. Correction: While some birds develop brighter beaks with maturity, color can also fluctuate seasonally due to hormones or diet (e.g., flamingos).

Clarifying these misunderstandings improves both scientific literacy and humane treatment of captive birds, where inappropriate handling or housing can lead to injury.

Scientific Research and Technological Inspiration

The study of bird beak composition has inspired innovations in materials science and engineering. Researchers analyzing the nanostructure of avian keratin have developed synthetic composites mimicking its strength-to-weight ratio. These biomimetic materials show promise in aerospace, protective gear, and medical implants.

Additionally, CT scans and 3D modeling now allow scientists to simulate stress distribution in beaks under various loads. Such research helps explain why certain shapes dominate particular ecosystems and informs conservation strategies for species facing habitat loss or climate change.

Understanding what bird beaks are made of isn’t merely academic—it contributes to real-world applications that benefit both wildlife and human technology.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are bird beaks made of the same material as claws?

- Yes, both bird beaks and claws are primarily composed of keratin, specifically a type called beta-keratin, which is stronger than the alpha-keratin found in humans.

- Can birds feel pain in their beaks?

- Yes, although the outer keratin layer has no nerves, the inner bony core is highly sensitive. Damage to the base or interior of the beak can cause significant pain.

- Do bird beaks grow continuously?

- Yes, the keratin layer grows constantly, similar to human nails. Natural wear keeps them at optimal length in healthy individuals.

- Why do some bird beaks change color?

- Color changes can signal breeding readiness, reflect diet (e.g., carotenoids in flamingos), or indicate health status. Seasonal hormonal shifts also affect pigmentation.

- How should I care for a pet bird’s beak?

- Provide appropriate chew toys, a nutritionally balanced diet, and regular veterinary checkups. Never attempt to trim your bird’s beak unless trained to do so.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4