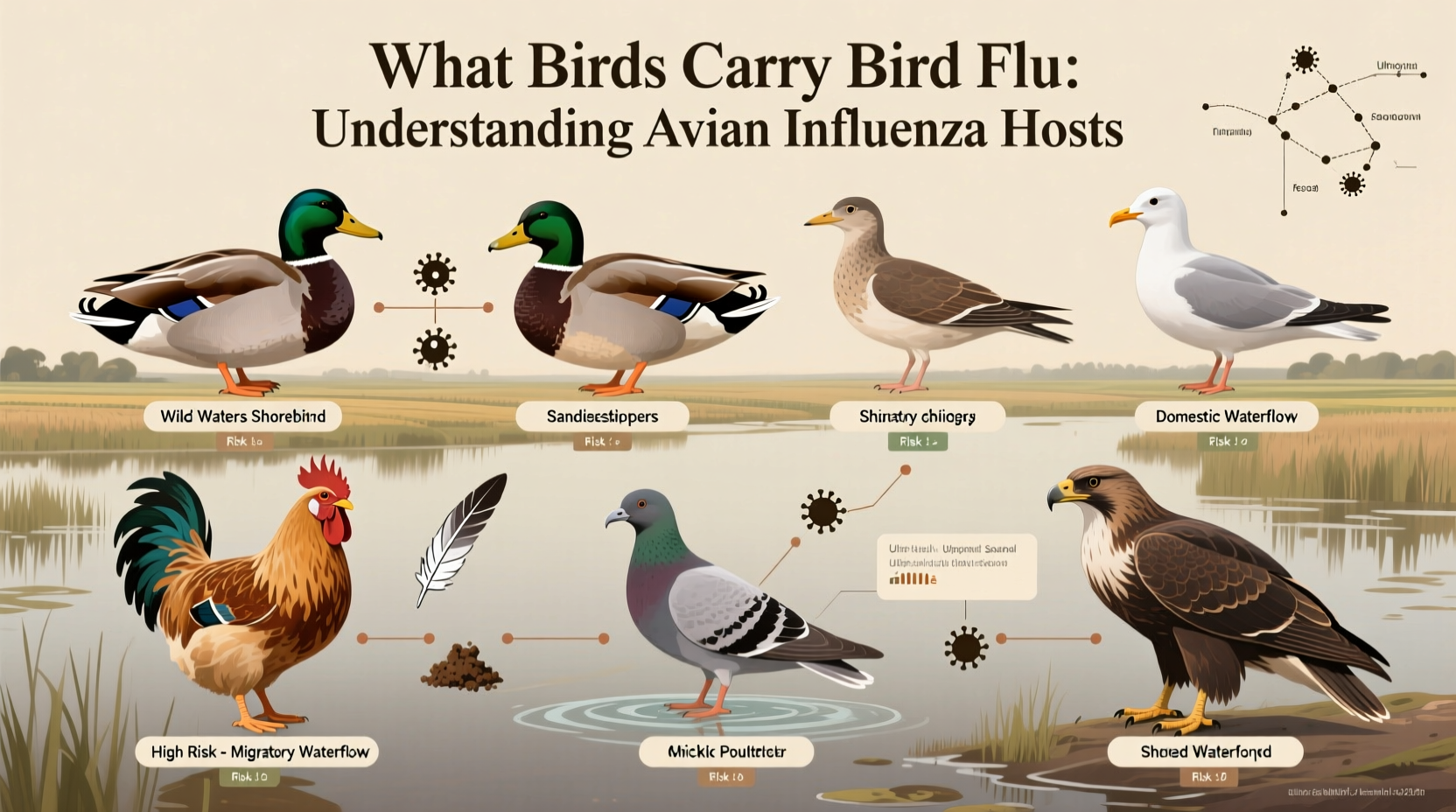

Birds that carry bird flu primarily include wild waterfowl and domestic poultry, with ducks, geese, swans, and chickens being among the most common hosts of avian influenza viruses. These species are central to the spread and maintenance of bird flu in both natural and agricultural environments. Understanding which birds carry bird flu is essential for public health, wildlife conservation, and commercial farming operations. The term 'what birds carry bird flu' reflects growing public interest in identifying high-risk species—especially as outbreaks continue to emerge globally in 2024 and beyond.

Understanding Avian Influenza: A Biological Overview

Avian influenza, commonly known as bird flu, refers to a group of influenza A viruses that naturally circulate among birds. While over 100 bird species have been documented to carry some form of the virus, not all experience illness or transmit it efficiently. The H5N1 and H7N9 subtypes are particularly concerning due to their high pathogenicity (ability to cause severe disease) in poultry and occasional transmission to humans.

The virus primarily targets the respiratory, digestive, and nervous systems of birds. It spreads through direct contact with infected birds or their secretions—including saliva, nasal discharge, and feces. Contaminated surfaces such as feeders, water sources, and farming equipment also play a role in transmission.

Wild Birds That Carry Bird Flu

Wild aquatic birds, especially those belonging to the order Anseriformes (ducks, geese, and swans), are considered the natural reservoirs of avian influenza viruses. These birds often carry low-pathogenic strains without showing symptoms, allowing them to spread the virus across long distances during migration.

- Ducks: Mallards and other dabbling ducks frequently harbor avian influenza without becoming ill, making them silent carriers.

- Geese: Both Canada geese and domesticated breeds can contract and shed the virus, posing risks to nearby poultry farms.

- Swans: Mute swans and whooper swans have tested positive for highly pathogenic H5N1, sometimes succumbing to the disease.

- Shorebirds and waders: Species like gulls, terns, and sandpipers may pick up the virus from contaminated wetlands and contribute to regional spread.

Migratory patterns significantly influence the geographic distribution of bird flu. For example, outbreaks in North America often coincide with spring and fall migrations along major flyways such as the Atlantic and Mississippi routes. Monitoring these movements helps predict where new cases might appear.

Domestic Poultry Most Affected by Bird Flu

While wild birds typically tolerate the virus, domestic poultry—including chickens, turkeys, quails, and game birds—are highly susceptible to severe illness and death from highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). Once introduced into a commercial flock, the virus can spread rapidly, leading to mass culling to prevent further transmission.

| Bird Species | Natural Reservoir? | Symptoms Observed | Risk Level (Transmission) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mallard Duck | Yes | Rarely shows signs | High (carrier) |

| Chicken | No | Respiratory distress, drop in egg production | Very High (mortality) |

| Turkey | No | Lethargy, swollen head, sudden death | Very High |

| Canada Goose | Yes | Mild to moderate illness | Moderate |

| Pigeon | No | Rarely infected | Low |

Backyard flocks are especially vulnerable because they may lack biosecurity measures present on larger farms. Owners should monitor local health advisories and avoid letting birds roam freely if an outbreak is reported nearby.

Do Songbirds and Raptors Carry Bird Flu?

Recent evidence suggests that certain songbirds and birds of prey can become infected, though they are not primary carriers. In 2023–2024, several cases were documented in crows, jays, hawks, and owls—likely due to scavenging infected carcasses rather than airborne transmission.

While passerines (perching birds) generally do not play a major role in spreading bird flu, their involvement highlights how the virus can move beyond waterfowl and poultry into broader ecosystems. This raises concerns for biodiversity and ecosystem health, especially when endangered raptors are affected.

Cultural and Symbolic Implications of Bird Flu Outbreaks

Birds hold powerful symbolic meanings across cultures—from freedom and spirituality to omens and messengers. When diseases like bird flu threaten entire populations, these cultural narratives shift. For instance, swans, traditionally symbols of grace and fidelity, have appeared in media coverage as potential vectors of disease, altering public perception.

In agricultural communities, chickens and ducks are not only economic assets but also part of culinary traditions and religious practices. Mass culling during outbreaks can lead to emotional and cultural loss, beyond financial impact. Ritual slaughter bans or restrictions during epidemic periods disrupt customary observances, prompting debate about balancing public safety with cultural rights.

Meanwhile, migratory birds symbolize global interconnectedness. Their role in spreading bird flu underscores how ecological systems transcend borders—a concept increasingly relevant in discussions about pandemic preparedness and One Health approaches linking animal, human, and environmental well-being.

How to Identify Signs of Bird Flu in Wild and Domestic Birds

Early detection is key to controlling outbreaks. Common clinical signs in infected birds include:

- Sudden death without prior symptoms

- Loss of appetite and energy

- Decreased egg production or soft-shelled eggs

- Nasal discharge, coughing, or sneezing

- Swelling around the eyes, neck, or head

- Torticollis (twisted neck) or other neurological signs

If you observe multiple dead birds—especially waterfowl or raptors—in a localized area, report them to your state’s wildlife agency or national veterinary authority. Do not handle dead birds with bare hands; use gloves and disinfect any tools used in disposal.

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures for Bird Owners

Whether managing a backyard coop or a large-scale farm, implementing strong biosecurity protocols reduces the risk of introducing bird flu. Key steps include:

- Isolate new or returning birds for at least 30 days before integrating them into an existing flock.

- Control access to coops—limit visitors and require footwear changes or disinfection mats at entry points.

- Protect feed and water sources from contamination by wild birds using covered containers.

- Avoid visiting other poultry farms or live markets during active outbreak periods.

- Vaccinate when available and recommended, although vaccines do not always prevent infection, only reduce severity.

During peak migration seasons (March–May and September–November), extra vigilance is advised. Some regions issue temporary housing orders requiring indoor confinement of poultry when virus levels in wild birds rise.

Global Surveillance and Reporting Systems

Organizations such as the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintain real-time surveillance networks to track avian influenza outbreaks. Public dashboards provide updated maps showing current hotspots.

Citizen scientists and birdwatchers can contribute by reporting sick or dead birds through platforms like eBird or government-run hotlines. Accurate data collection enables faster response and better modeling of future risks.

Human Risk and Public Health Considerations

Although bird flu does not easily infect humans, sporadic cases—mostly linked to close contact with infected poultry—have occurred. As of mid-2024, no sustained human-to-human transmission has been confirmed, but health agencies remain vigilant due to the virus’s potential to mutate.

People working with birds should wear protective gear and practice good hygiene. Consuming properly cooked poultry and eggs poses no risk, as heat destroys the virus. However, raw egg products or undercooked meat from infected animals could be hazardous.

Common Misconceptions About What Birds Carry Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza and its hosts:

- Myth: All birds carry bird flu.

Fact: Only certain species, mainly waterfowl and poultry, are significant carriers. - Myth: Pet birds like parrots or canaries are at high risk.

Fact: They are rarely affected unless exposed to infected wild birds or contaminated materials. - Myth: Culling wild birds controls the virus.

Fact: This approach is ineffective and ecologically damaging; focus remains on protecting domestic flocks and monitoring migration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Which birds are most likely to carry bird flu?

Ducks, geese, swans, and chickens are the most common carriers. Wild waterfowl serve as natural reservoirs, while domestic poultry suffer high mortality rates when infected.

Can songbirds spread bird flu?

Songbirds can become infected, usually by scavenging, but they are not major transmitters. Cases remain rare and localized.

Should I stop feeding wild birds during a bird flu outbreak?

Public health officials may recommend pausing bird feeding if local outbreaks occur, as feeders can concentrate birds and increase transmission risk. Clean feeders regularly with a 10% bleach solution if used.

Is there a vaccine for bird flu in birds?

Vaccines exist for certain strains and are used selectively in poultry, but they don’t eliminate shedding and are not universally applied.

How can I protect my backyard chickens from bird flu?

Keep them indoors during outbreak alerts, prevent contact with wild birds, sanitize equipment, and report unusual deaths immediately to local authorities.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4