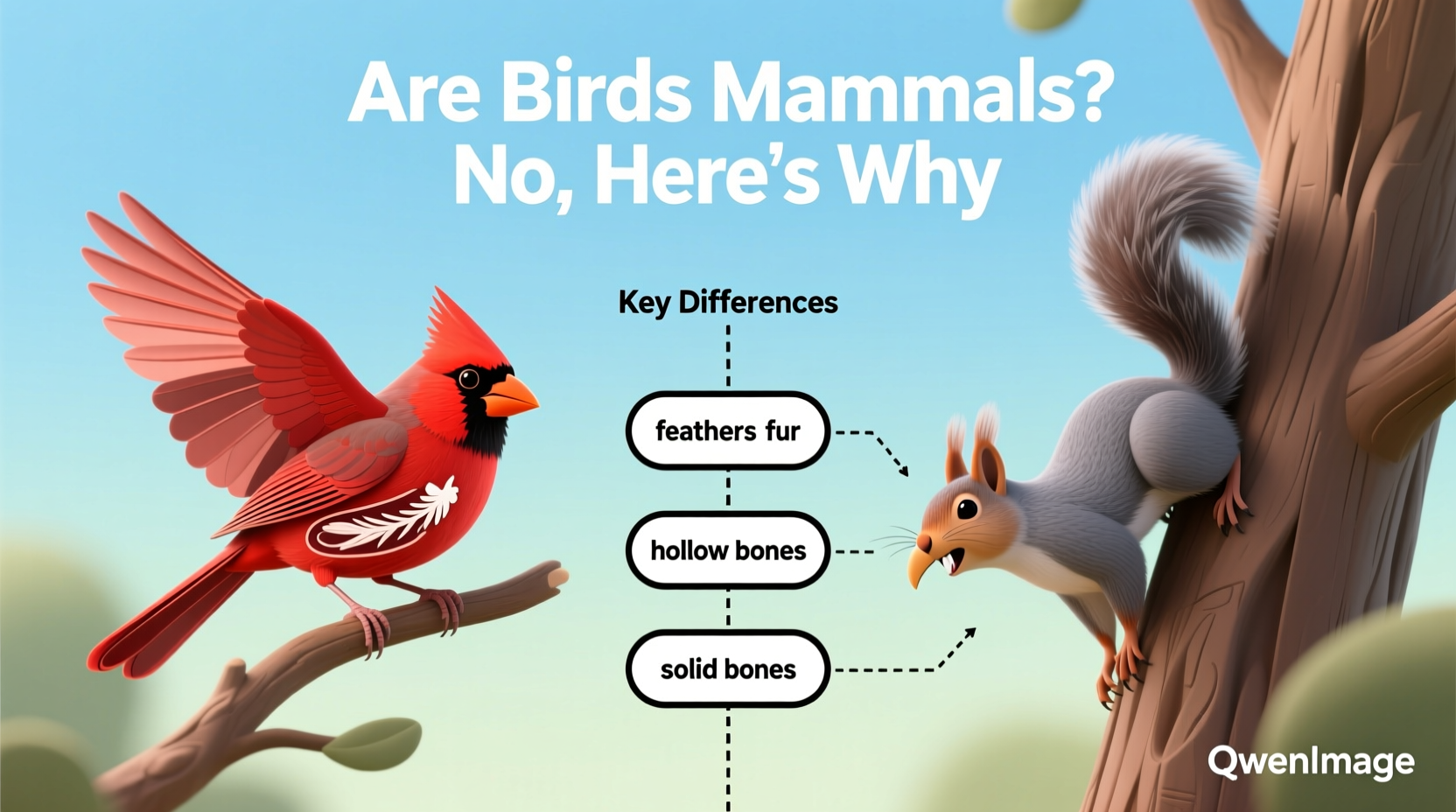

Birds are not mammals—this is a fundamental distinction in animal classification. While both birds and mammals are warm-blooded vertebrates, what do birds have that sets them apart from mammals? Feathers, egg-laying reproduction, beaks, and a uniquely efficient respiratory system define avian biology. Unlike mammals, which nourish their young with milk and possess hair or fur, birds belong to the class Aves, a separate evolutionary lineage that diverged from reptiles over 150 million years ago. Understanding what do birds biologically and ecologically reveals why they occupy a distinct place in the tree of life, despite sharing some traits like endothermy and complex behaviors with mammals.

Biological Classification: What Makes a Bird a Bird?

The scientific classification of birds places them in the kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, and class Aves. This categorization is based on a suite of anatomical and physiological features unique to birds. One of the most definitive traits is the presence of feathers—no other animal group possesses true feathers. These specialized structures evolved from reptilian scales and serve multiple functions: insulation, flight, and display.

Another key characteristic is that birds lay hard-shelled eggs. While some mammals (like the platypus) also lay eggs, they are exceptions among mammals, which typically give birth to live young. Birds reproduce through internal fertilization, but embryonic development occurs externally in the egg. This reproductive strategy contrasts sharply with placental mammals, where embryos develop inside the mother’s body.

Birds also have lightweight skeletons made of hollow bones, which reduce body mass and facilitate flight. Their skeletal structure includes a fused collarbone (the furcula or “wishbone”) and a keeled sternum that anchors powerful flight muscles. In contrast, mammalian skeletons are generally denser and adapted for walking, running, or swimming rather than aerial locomotion.

Metabolism and Thermoregulation: Warm-Blooded But Different

Both birds and mammals are endothermic, meaning they generate internal heat to maintain a constant body temperature. However, birds typically have higher metabolic rates than mammals. For example, the average bird’s body temperature ranges from 104°F to 108°F (40°C to 42°C), compared to 98.6°F (37°C) in humans. This elevated metabolism supports the high energy demands of flight.

To sustain this energy output, birds have highly efficient respiratory and circulatory systems. Their lungs are connected to a network of air sacs that allow for unidirectional airflow, ensuring a continuous supply of oxygen—even during exhalation. This is unlike the tidal breathing system in mammals, where air moves in and out of the same pathway. This adaptation makes avian respiration one of the most efficient in the animal kingdom.

Reproduction and Parental Care: How Birds Raise Their Young

While birds do not produce milk or possess mammary glands, many species exhibit extensive parental care. Both parents often incubate eggs and feed hatchlings, a behavior seen in robins, eagles, and penguins. The absence of lactation does not imply lesser care; instead, birds feed their young by regurgitating food, a method that efficiently transfers nutrients.

Nesting behaviors vary widely across species. Some birds, like the cuckoo, practice brood parasitism—laying eggs in other birds’ nests. Others, such as weaver birds, construct elaborate nests using grass and twigs. These diverse strategies reflect adaptations to different environments and ecological niches.

Evolutionary Origins: From Dinosaurs to Modern Birds

Fossil evidence overwhelmingly supports the theory that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period. The discovery of Archaeopteryx in the 1860s provided a crucial transitional fossil, showing both reptilian features (teeth, long bony tail) and avian traits (feathers, wings). More recent finds, such as feathered dinosaurs in China, have further solidified the dinosaur-bird link.

This evolutionary history explains why birds share certain skeletal features with reptiles, including scaly legs and a single middle ear bone. Despite their dinosaur ancestry, modern birds are considered the only living descendants of dinosaurs, making them a vital group for understanding prehistoric life.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds

Beyond biology, birds hold profound cultural and symbolic meanings across civilizations. In ancient Egypt, the ibis was associated with Thoth, the god of wisdom. Native American tribes often view the eagle as a sacred messenger between humans and the divine. In Christianity, the dove symbolizes peace and the Holy Spirit.

In literature and art, birds frequently represent freedom, transcendence, and the soul. The phoenix, a mythical bird that rises from its ashes, appears in Greek, Egyptian, and Chinese traditions as a symbol of renewal. Meanwhile, ravens feature prominently in Norse mythology and the works of Edgar Allan Poe, embodying mystery and intelligence.

These symbolic roles influence how humans interact with birds today. Conservation efforts often gain momentum when charismatic species like bald eagles or flamingos become national icons. Understanding what do birds mean culturally enhances public engagement in wildlife protection.

Practical Guide to Birdwatching: Tips for Beginners

For those interested in observing birds firsthand, birdwatching (or “birding”) offers a rewarding way to connect with nature. To get started:

- Invest in binoculars: Choose a model with 8x or 10x magnification and a wide field of view.

- Use a field guide: Apps like Merlin Bird ID or books like The Sibley Guide to Birds help identify species by appearance, song, and habitat.

- Visit diverse habitats: Parks, wetlands, forests, and even urban gardens attract different bird species.

- Go early in the morning: Most birds are active at dawn when temperatures are cooler and predators are fewer.

- Keep a journal: Record sightings, behaviors, and weather conditions to track patterns over time.

Joining local birding groups or attending guided walks can also enhance learning. Many organizations, such as the Audubon Society, offer citizen science programs where amateurs contribute data on bird populations and migration trends.

Common Misconceptions About Birds

Despite widespread fascination, several myths persist about birds. One common misconception is that all birds can fly. In reality, flightless birds like ostriches, emus, and kiwis have evolved in isolated environments with few predators, reducing the need for flight.

Another myth is that birds abandon their young if touched by humans. Most birds have a poor sense of smell and will not reject chicks due to human scent. However, it’s still best to avoid handling wild birds to prevent stress or injury.

Some people believe that feeding birds year-round is always beneficial. While supplemental feeding helps in winter, it can lead to dependency or disease spread if feeders are not cleaned regularly. Experts recommend removing feeders in summer unless providing specific foods like nectar for hummingbirds.

Regional Differences in Bird Species and Behavior

Bird diversity varies dramatically by region. Tropical areas like the Amazon rainforest host over 1,300 bird species, while arid deserts may have only a few dozen. Migration patterns also differ: North American warblers travel thousands of miles between breeding and wintering grounds, whereas many Australian birds are sedentary due to stable climates.

Urbanization impacts bird populations differently around the world. In Europe, house sparrows have declined due to habitat loss, while in parts of Asia, mynas thrive in cities. Climate change is altering migration timing and ranges, pushing some species toward higher latitudes.

To stay informed about local bird activity, consult regional resources such as eBird.org, which aggregates real-time observations from birders worldwide. Checking with local wildlife agencies can also reveal seasonal events like hawk migrations or shorebird gatherings.

| Feature | Birds | Mammals |

|---|---|---|

| Skin Covering | Feathers | Hair/Fur |

| Reproduction | Egg-laying | Live birth (mostly) |

| Young Feeding | Regurgitation | Milk from mammary glands |

| Skeleton | Hollow bones | Dense bones |

| Respiration | One-way airflow with air sacs | Tidal breathing (in-out) |

How to Verify Bird Information Accurately

With so much misinformation online, it’s essential to rely on credible sources. Peer-reviewed journals like The Auk or Ornithological Applications publish scientific findings on bird biology. Government agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service provide data on endangered species and conservation status.

When identifying birds, cross-reference multiple sources. If an app suggests a rare sighting, verify it with regional checklists or report it to citizen science platforms for expert review. Always consider seasonal occurrence—seeing a snow goose in Florida during winter is plausible, but unlikely in July.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are bats birds?

- No, bats are mammals. They give birth to live young and nurse them with milk, despite being capable of flight.

- Do any birds give live birth?

- No, all birds lay eggs. There are no known species of birds that give birth to live young.

- Why aren’t birds classified as mammals?

- Birds lack key mammalian traits like hair, mammary glands, and live birth. Their feathers, egg-laying, and skeletal structure place them in a separate class.

- Can birds sweat?

- No, birds do not have sweat glands. They regulate body temperature by panting, fluttering their throat (gular fluttering), or spreading wings to release heat.

- What is the closest living relative to birds?

- Crocodilians (crocodiles and alligators) are the closest living relatives to birds, sharing a common ancestor from the archosaur group.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4