The term 'barb bird wing' refers to the structural components of a feather, specifically the barbs that extend from the central shaft (rachis) and form the vane of the feather. These barbs are critical in flight mechanics, insulation, and display among birds. Understanding what is a barb bird wing reveals not only the intricate biology of avian flight but also the evolutionary adaptations that allow birds to thrive in diverse environments. The barbs, along with their smaller branches called barbules and hook-like structures known as barbicels, interlock to create a smooth, aerodynamic surface essential for lift and maneuverability during flight.

Anatomy of a Feather: Breaking Down the Barb and Beyond

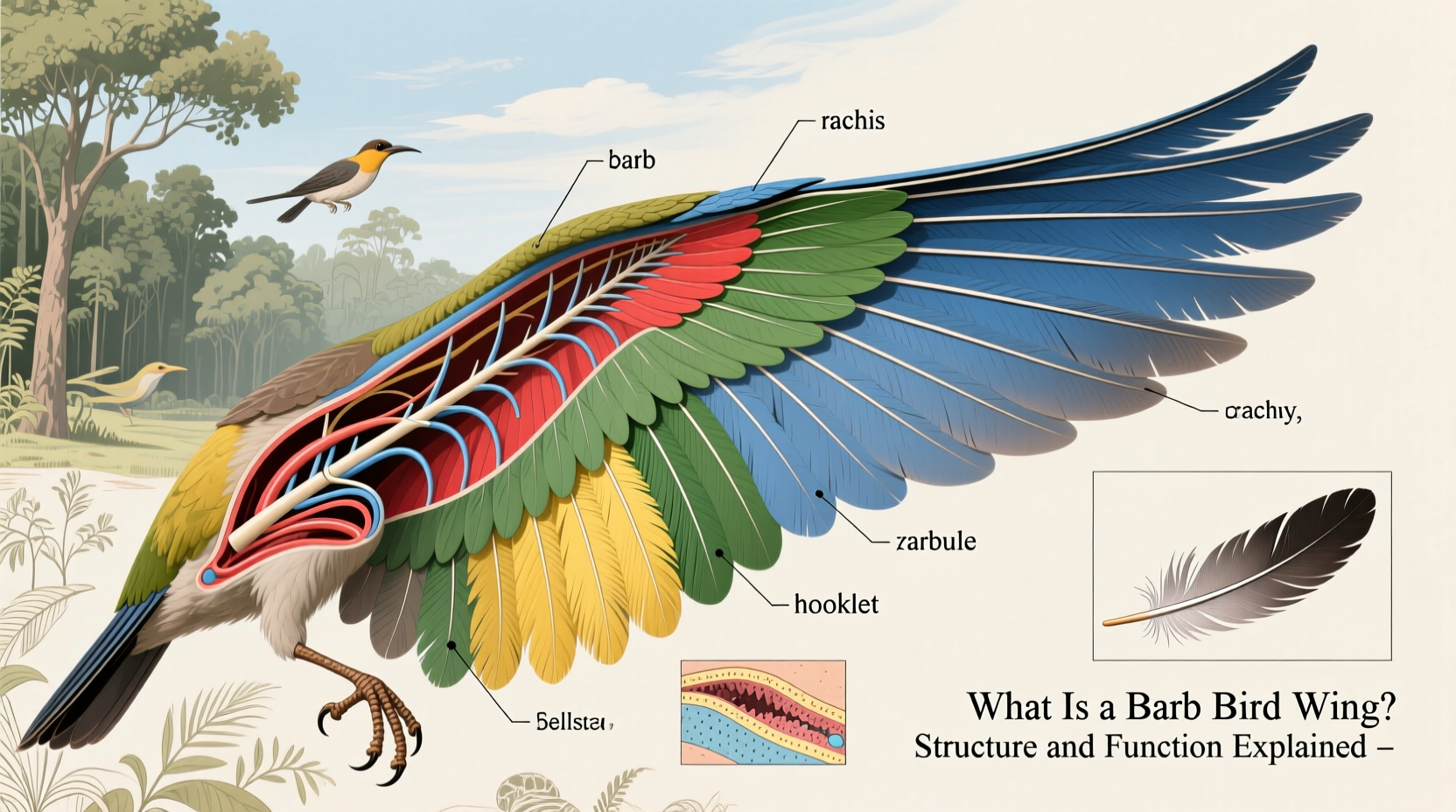

To fully grasp what is a barb bird wing, one must first understand feather microstructure. A typical contour feather—such as those found on wings or tails—consists of several key parts: the calamus (the hollow base inserted into the skin), the rachis (the main central shaft), and the vanes formed by barbs branching off on either side of the rachis.

Each barb further divides into smaller filaments called barbules. These barbules have tiny hooks (barbicels) that zip adjacent barbules together like Velcro, forming a continuous surface. This structure is vital for flight feathers, where even minor damage can disrupt airflow and reduce flying efficiency. When a bird preens, it is often re-zipping these barbules back into alignment.

Biological Function of Barbs in Avian Flight

The role of barbs in bird wings cannot be overstated. They contribute directly to the aerodynamics necessary for powered flight. By creating a cohesive vane, the interlocking barbs ensure that air flows smoothly over the wing’s surface, generating lift while minimizing drag. Different species exhibit variations in barb density and stiffness depending on their flight style. For example, fast-flying birds like falcons have tightly packed, rigid barbs, whereas soaring birds such as eagles may have more flexible vanes allowing fine adjustments in glide dynamics.

In addition to flight, barbs play roles in thermoregulation and waterproofing. Down feathers, which lack strong barbicels, trap air close to the body for insulation. Waterfowl have densely barbed contour feathers coated with oil from the uropygial gland, enhancing water resistance.

Barb Structure Across Bird Species: Adaptations and Variations

Variation in barb structure reflects ecological specialization. Nocturnal birds like owls possess soft-edged barbs that break up turbulence, enabling silent flight crucial for hunting. In contrast, songbirds have brightly colored barbs due to pigmentation or structural coloration—microscopic arrangements that refract light, producing iridescence without pigments.

Flightless birds such as ostriches still retain well-developed barbs, though their function shifts toward display and temperature regulation rather than flight. Peacocks, for instance, use elongated, ornamented barbs in courtship displays, where visual signaling outweighs aerodynamic necessity.

Symmetry and Integrity: How Birds Maintain Their Barb Network

Maintaining the integrity of feather barbs is essential for survival. Birds spend significant time preening to repair misaligned barbs. During preening, they run their beaks through feathers, applying pressure that reconnects separated barbules. Some species also engage in anting—rubbing ants or other acidic substances through feathers—which may help control parasites that could weaken barb structure.

Feather wear accumulates over time, especially in migratory species. Seasonal molting allows birds to replace damaged feathers entirely, ensuring optimal barb performance year-round. Molting patterns vary widely; some birds molt gradually, retaining flight ability, while others undergo simultaneous molts, becoming temporarily flightless.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Feathers and Barbs

While 'what is a barb bird wing' primarily addresses biological structure, the cultural resonance of feathers runs deep across human societies. Indigenous cultures around the world have revered feathers for spiritual and ceremonial uses. The intactness of barbs symbolizes purity, strength, and connection to the sky or divine realms.

In Native American traditions, eagle feathers with fully aligned barbs are considered sacred honors, earned through acts of bravery or service. Similarly, Maori warriors in New Zealand adorned cloaks with kiwi or albatross feathers, where the quality and symmetry of barbs reflected status and lineage.

In modern symbolism, the image of a perfect feather—its barbs neatly zipped—often represents peace, freedom, or transcendence. Conversely, a broken or frayed feather may signify loss or vulnerability, echoing the fragility of life itself.

Observing Barbs in the Field: Tips for Birdwatchers

For amateur and professional ornithologists alike, observing barb structure can enhance identification and appreciation of avian species. High-quality binoculars or spotting scopes allow close inspection of feather details, particularly during perching or preening behaviors.

When identifying birds, note differences in wing shape and feather texture. Raptors typically show stiff, sharply defined barbs visible at moderate magnification. Waterfowl exhibit sleek, overlapping vanes with tightly sealed barbs that glisten when wet. Songbirds may reveal subtle iridescence caused by microscopic barbule structures diffracting sunlight.

Photographers should use macro lenses to capture barb detail. Early morning light reduces glare and highlights feather microstructures. Always maintain ethical distances to avoid disturbing natural behaviors like preening or molting.

Common Misconceptions About Feather Barbs

A frequent misunderstanding is that all feathers serve flight purposes. While barbs in wing and tail feathers are adapted for aerodynamics, many feathers serve insulation, camouflage, or communication. Down feathers, for example, have loose barbs with no hooklets, maximizing air-trapping capability.

Another myth is that once barbs separate, they cannot be repaired. Birds naturally restore most feather damage through preening. Only severe trauma or contamination (e.g., oil spills) permanently compromises barb function.

Lastly, some believe that feather color comes solely from pigments. However, many vibrant hues—especially blues and greens—are the result of nanostructures within barbules that scatter light selectively, a phenomenon known as structural coloration.

Scientific Research and Technological Applications Inspired by Barb Mechanics

The study of barb and barbule interactions has inspired innovations in materials science and aerospace engineering. Researchers have developed bio-inspired adhesives mimicking the self-repairing mechanism of feather barbules. These zipping systems offer reusable fasteners with low energy cost and high durability.

In aviation, engineers analyze how barb flexibility affects lift distribution across bird wings. Micro-air vehicles (MAVs) now incorporate morphing wing designs based on avian feather dynamics, improving agility and fuel efficiency.

Conservation biologists also examine barb condition as an indicator of environmental health. Pollutants like mercury or pesticides can weaken keratin structure, leading to brittle barbs and poor flight performance—a sign of ecosystem stress.

How to Support Avian Health and Feather Integrity

Protecting wild bird populations ensures the preservation of complex feather adaptations like barbs. Habitat conservation, reduction of pesticide use, and responsible pet ownership all contribute to healthier plumage.

Backyard bird enthusiasts can provide clean water sources for bathing, which helps birds maintain feather alignment. Avoid using chemical-laden cleaners near birdbaths, as residues can degrade barbule connections.

During migration seasons, minimize window collisions by installing UV-reflective decals. Impact injuries often shear off barbs or fracture rachises, impairing flight until replacement occurs during molt.

| Bird Type | Barb Characteristics | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Falcon | Stiff, densely packed barbs | High-speed flight, precision diving |

| Owl | Soft fringes, velvety barbs | Silent flight, noise dampening |

| Duck | Oily, tightly interlocked barbs | Waterproofing, buoyancy |

| Peacock | Elongated, iridescent barbs | Sexual display, mate attraction |

| Ostrich | Loose, hair-like barbs | Thermoregulation, display |

Frequently Asked Questions

- What exactly is a barb on a bird's wing? A barb is a branch extending from the central shaft of a feather that forms part of the vane. Multiple barbs align side-by-side and connect via barbules to create a functional surface for flight, insulation, or display.

- Do all feathers have the same type of barbs? No. Barb structure varies significantly between feather types (flight, down, contour) and species. Flight feathers have strong, interlocking barbs, while down feathers have loose, fluffy barbs designed for warmth.

- Can damaged barbs be fixed by birds? Yes. Birds routinely repair separated barbs by preening, using their beaks to zip barbules back together. Only extensive damage requires waiting for the next molt cycle.

- How do barbs help birds fly? Interconnected barbs form a continuous, lightweight, and flexible airfoil surface that generates lift and controls airflow, essential for stable and efficient flight.

- Are barbs made of the same material as human hair? Yes. Both bird feather barbs and human hair are primarily composed of beta-keratin, a tough, fibrous protein that provides structural strength and resilience.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4