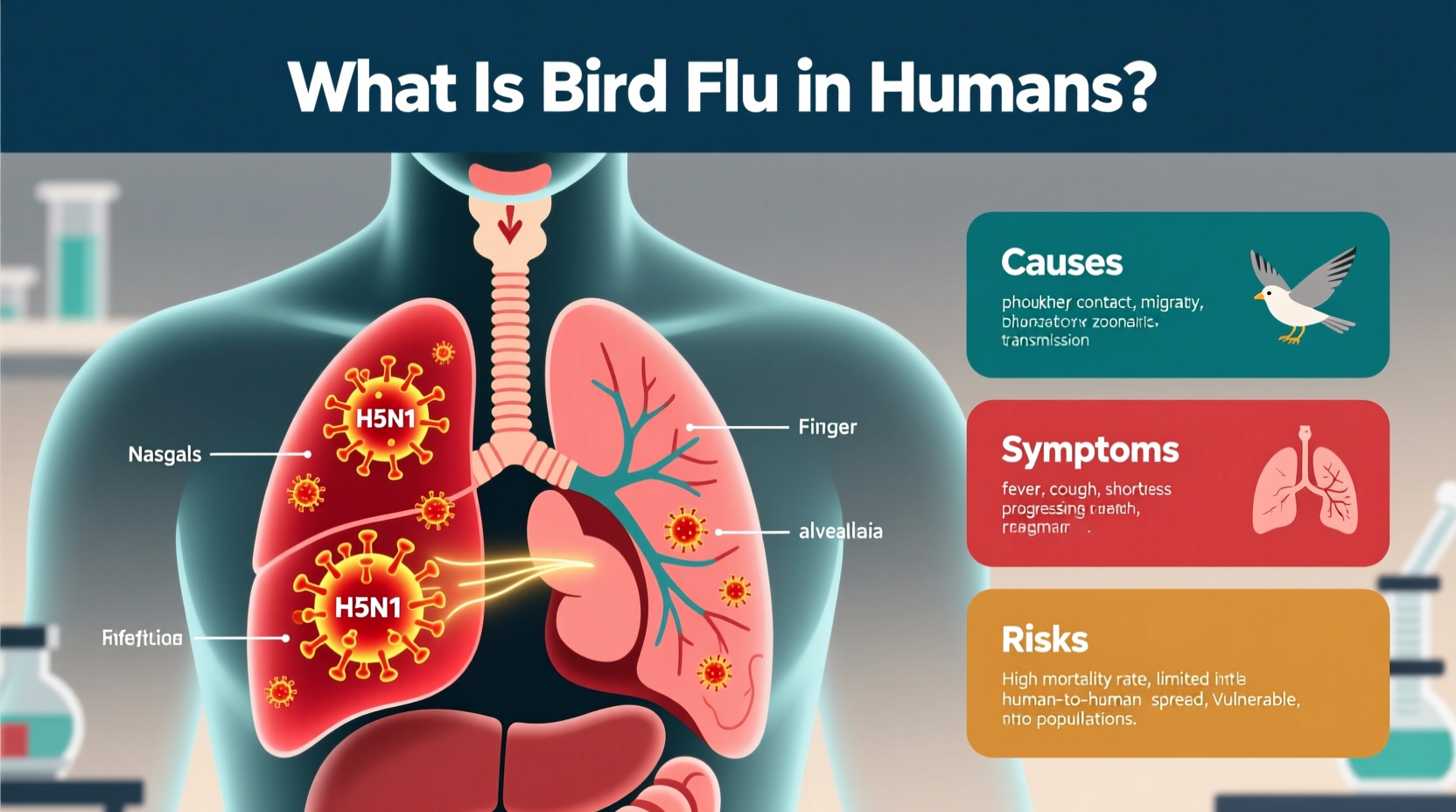

Bird flu in humans, also known as avian influenza, is a rare but potentially severe respiratory illness caused by certain strains of influenza viruses that primarily infect birds. The most common subtype known to infect humans is H5N1, though other variants such as H7N9 and H5N6 have also been reported. Human cases typically occur after close contact with infected poultry or contaminated environments, not through eating properly cooked poultry or eggs. Understanding what is bird flu in humans involves recognizing its origins in wild and domestic birds, how it spreads, and the public health measures in place to prevent outbreaks.

Origins and Biology of Avian Influenza

Avian influenza viruses belong to the family Orthomyxoviridae and are classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, leading to various combinations like H5N1, H7N9, and H9N2. These viruses naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, and shorebirds, which often carry the virus without showing symptoms.

The virus can spread from wild birds to domestic poultry through direct contact or via contaminated water, feed, or equipment. Once introduced into commercial or backyard flocks, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) strains—such as H5N1—can cause rapid and deadly outbreaks, wiping out entire flocks within days. This not only affects food security and agriculture but also increases the risk of spillover into humans.

How Bird Flu Spreads to Humans

Transmission of bird flu to humans usually requires close and prolonged exposure to infected birds or their droppings, secretions, or contaminated surfaces. Most human cases have occurred in individuals who work with poultry—such as farmers, slaughterhouse workers, or live bird market vendors. There is currently no sustained human-to-human transmission of H5N1, meaning the virus does not easily spread between people like seasonal flu.

However, scientists remain concerned about the potential for genetic reassortment—when an animal or human host is co-infected with both avian and human influenza viruses. This could lead to a new strain capable of efficient human-to-human transmission, potentially triggering a pandemic. Monitoring these zoonotic events is critical for global health preparedness.

Symptoms and Diagnosis in Humans

Symptoms of bird flu in humans can range from mild to life-threatening. Early signs may resemble seasonal influenza: fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and fatigue. However, the disease can rapidly progress to severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ failure, and death. The case fatality rate for H5N1 infection in humans has historically been high—over 50% in some outbreaks—though this figure may be inflated due to underreporting of milder cases.

Diagnosis requires laboratory testing, typically using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on respiratory samples such as nasal swabs or throat washes. Rapid antigen tests used for seasonal flu are not reliable for detecting avian influenza. Anyone with recent exposure to sick or dead birds and developing flu-like symptoms should seek medical attention immediately and inform healthcare providers of their exposure history.

Global Cases and Outbreak History

The first documented case of human infection with H5N1 occurred in Hong Kong in 1997, when 18 people were infected and six died. Since then, sporadic cases have been reported across Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there have been over 900 confirmed human cases of H5N1 since 2003, with clusters primarily linked to household or close-contact settings.

In recent years, particularly since 2021, there has been a significant increase in global avian influenza activity among wild and domestic birds. In 2024, multiple countries—including the United States, the United Kingdom, India, and several EU nations—reported widespread H5N1 outbreaks in poultry and wild birds. While human cases remain rare, isolated infections continue to occur, reinforcing the need for vigilance.

| Year | Reported Human Cases (H5N1) | Countries Affected | Notable Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 18 | Hong Kong | First known human outbreak; mass culling of poultry |

| 2003–2006 | Over 250 | Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Turkey | Largest number of cases; international concern |

| 2013 (H7N9) | Over 1,500 | China | Emergence of new strain with high mortality |

| 2022–2024 | ~30 (across all subtypes) | USA, UK, Cambodia, India | Widespread bird outbreaks; limited human cases |

Prevention and Public Health Measures

Preventing bird flu in humans starts with controlling the virus at its source: in bird populations. Key strategies include:

- Surveillance of wild bird migrations and early detection in poultry farms

- Rapid culling and safe disposal of infected flocks

- Biosecurity improvements on farms (e.g., limiting access, disinfecting equipment)

- Closing live bird markets during outbreaks

- Public education campaigns in high-risk areas

Treatment Options for Infected Individuals

Antiviral medications such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), and peramivir (Rapivab) are recommended for treating bird flu in humans, especially when administered early in the course of illness. These drugs work by inhibiting viral replication and may reduce severity and duration of symptoms. In severe cases, patients may require hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care support.

Vaccines for avian influenza exist but are not widely available to the general public. They are stockpiled by governments as part of pandemic preparedness plans. Seasonal flu vaccines do not protect against bird flu strains. Research is ongoing to develop universal influenza vaccines that could offer broader protection against multiple subtypes.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about bird flu and its risks to humans:

- Misconception: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and eggs pose no risk. The virus is destroyed at normal cooking temperatures. - Misconception: Bird flu spreads easily from person to person.

Fact: No sustained human-to-human transmission has been documented. Close, unprotected contact with infected birds remains the primary route. - Misconception: Only rural or developing regions face risks.

Fact: Global travel and trade mean outbreaks anywhere can have international implications. Urban populations are not immune to indirect exposure.

Travel and Safety Advice for High-Risk Regions

Travelers visiting areas experiencing avian influenza outbreaks should take precautions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises avoiding poultry farms, live bird markets, and places where birds are slaughtered. Travelers should also practice frequent handwashing and avoid touching surfaces that may be contaminated with bird droppings.

Before traveling, check the latest advisories from health authorities such as the CDC or WHO. Some countries implement temporary import bans on poultry products during outbreaks. Staying informed helps minimize personal risk and supports broader containment efforts.

Role of Climate Change and Environmental Factors

Emerging research suggests that climate change may influence the spread of bird flu. Changes in temperature, precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events can affect bird migration routes, timing, and congregation behaviors. These shifts may increase opportunities for virus transmission between wild and domestic birds.

Additionally, habitat loss and agricultural intensification bring humans and livestock into closer proximity with wildlife, raising the likelihood of zoonotic spillover. Addressing bird flu therefore requires a One Health approach—integrating human, animal, and environmental health monitoring and policy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can bird flu be transmitted through the air?

- While the virus can become airborne in dust or aerosols from dried feces, especially in enclosed spaces like poultry barns, it is not considered airborne in the same way as measles or tuberculosis. Transmission typically requires close proximity to infected birds.

- Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

- There are candidate vaccines for H5N1 and other subtypes, but they are not commercially available to the public. They are kept in national stockpiles for emergency use if a pandemic strain emerges.

- How long does it take for symptoms to appear after exposure?

- The incubation period for bird flu in humans ranges from 2 to 8 days, though it can extend up to 10 days in rare cases. Early medical evaluation is crucial if exposure is suspected.

- Are pet birds at risk of carrying bird flu?

- Pet birds can become infected if exposed to wild birds or contaminated materials. Owners should keep cages indoors, avoid contact with wild birds, and report any sudden bird deaths to local veterinary authorities.

- What should I do if I find a dead bird?

- Do not touch or handle the bird with bare hands. Report it to local wildlife or public health officials, who can safely collect and test it for avian influenza.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4