The term bird chest refers to the prominent, muscular region on the front of a bird's body that houses the pectoral muscles responsible for powering flight. This area, also known as the keel or sternum in ornithological terms, is a defining feature of most flying birds and plays a critical role in their ability to generate lift and thrust during flight. Understanding what a bird chest is involves exploring not only its biological function but also its significance in bird identification, health assessment, and evolutionary adaptation. Whether you're a seasoned birder or new to avian anatomy, recognizing the structure and purpose of the bird chest enhances both observational skills and appreciation for how birds are uniquely built for aerial life.

Anatomical Structure of the Bird Chest

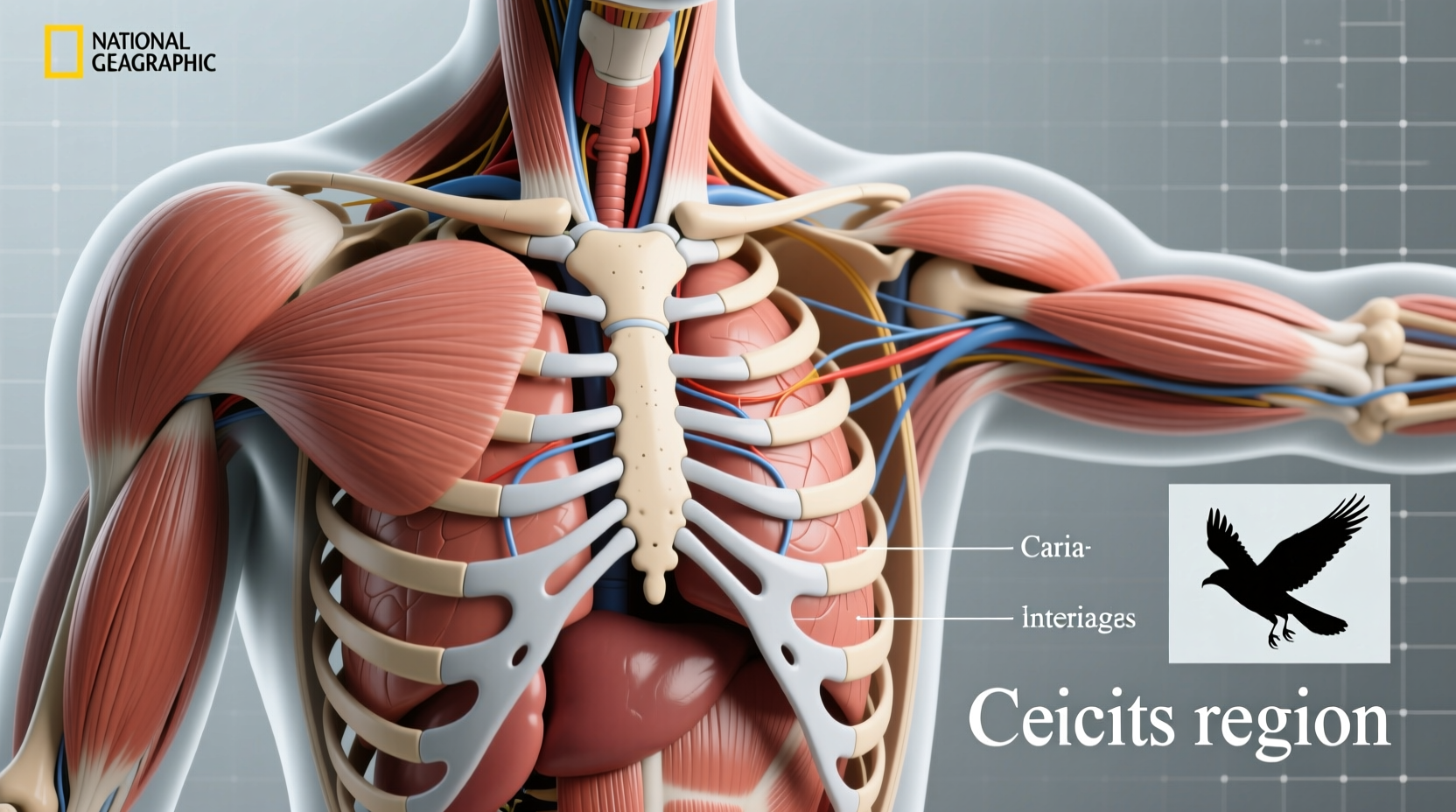

The bird chest is centered around the keel, or carina sterni, a large, blade-like extension of the sternum (breastbone) that projects outward from the ribcage. This bony ridge provides an expansive surface area for the attachment of two primary flight muscles: the pectoralis major and the supracoracoideus. The pectoralis major is the largest muscle in most birds and is responsible for the powerful downstroke of the wings. In highly aerial species like pigeons, albatrosses, and hummingbirds, this muscle can make up 15â25% of the birdâs total body weight.

Beneath the feathers, the bird chest often appears bulging or convexâespecially in strong fliersâdue to the dense development of these muscles. Unlike mammals, whose chests are dominated by respiratory structures and relatively smaller pectorals, birds have evolved a highly specialized thoracic design optimized for mechanical efficiency in flight. The entire skeletal framework supporting the bird chest, including the fused clavicles (wishbone), coracoid bones, and sternum, forms a rigid yet lightweight cage that withstands the immense forces generated during wingbeats.

Function in Flight and Locomotion

What makes the bird chest so essential is its direct involvement in avian locomotion. During flight, each wingbeat cycle relies on precise coordination between the muscles anchored to the keel. When the pectoralis major contracts, it pulls the wing downward, producing lift and forward propulsion. Simultaneously, the supracoracoideus, which runs beneath the pectoralis and connects via a tendon through the shoulder joint, powers the upstrokeâa unique pulley-like mechanism found only in birds.

This dual-muscle system allows for rapid, controlled wing movement, enabling everything from sustained soaring in raptors to hovering in hummingbirds. Birds with underdeveloped keels, such as flightless species like ostriches and kiwis, have significantly reduced pectoral musculature. Their bird chest appears flatter and less pronounced, reflecting their terrestrial lifestyle. Thus, the size and shape of the bird chest serve as reliable indicators of a speciesâ flight capabilities.

Variations Across Bird Species

Different bird groups exhibit distinct adaptations in their bird chest morphology based on ecological niches and behavioral patterns. For example:

- Passerines (songbirds): Moderate keel development supports short bursts of flight and agile maneuvering.

- Raptors (eagles, hawks): Deep keels support powerful, sustained flight needed for hunting and migration.

- Waterfowl (ducks, geese): Large pectoral muscles allow for fast takeoffs and long migratory flights.

- Hummingbirds: Exceptionally high proportion of chest muscle mass (up to 30%) enables hovering and backward flight.

- Flightless birds: Flat or vestigial keels reflect loss of flight; energy is redirected toward leg strength.

These variations illustrate how natural selection has shaped the bird chest across evolutionary time. By comparing the chest structure of different species, researchers can infer historical shifts in locomotor behavior and environmental pressures.

Role in Bird Identification and Field Observation

For birdwatchers, understanding what a bird chest looks like in various postures and lighting conditions improves identification accuracy. While plumage coloration and beak shape are commonly used markers, the contour of the chest can help distinguish similar-looking species. For instance, a sharply defined, rounded chest may indicate a healthy, well-muscled individual capable of long-distance migration, while a sunken or asymmetrical chest could signal malnutrition or injury.

In field guides and digital apps, illustrations often emphasize the silhouette of a bird, including the prominence of the chest. Observers are encouraged to note whether the chest appears broad, narrow, flat, or bulging when assessing unknown specimens. Additionally, certain behaviorsâsuch as puffing out the chest during courtship displays in grouse or dovesâare directly linked to the visibility and presentation of this anatomical region.

| Bird Group | Keel Development | Chest Muscle Mass | Flight Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albatross | Deep | High | Dynamic soaring |

| Pigeon | Very deep | Very high | Powered flight |

| Ostrich | Reduced | Low | Flightless |

| Kingfisher | Moderate | Moderate | Darting dives |

| Hummingbird | Deep relative to size | Extremely high | Hovering |

Cultural and Symbolic Meanings of the Bird Chest

Beyond biology, the image of a proud, expanded bird chest carries symbolic weight in human cultures. In many traditions, birds puffing out their chests represent confidence, vitality, or territorial dominance. The pigeonâs cooing display, the roosterâs strut, and the peacockâs fanâall involve accentuating the chest area to communicate status or attract mates.

In heraldry and art, birds depicted with full, robust chests symbolize courage, freedom, and divine messenger roles. Ancient Egyptians associated the falconâs powerful formâwith its prominent chest and keen eyesightâwith solar deities like Horus. Similarly, in Native American symbolism, eagles are revered not just for their flight but for their strong, commanding presence, embodied in part by their muscular build.

Even in modern language, phrases like âpuffing oneâs chestâ derive from avian behavior, illustrating how deeply bird physiology influences human expression and metaphor.

Health Assessment and Conservation Implications

Veterinarians and wildlife rehabilitators use the condition of a birdâs chest as a key diagnostic tool. A technique called keel scoring evaluates the amount of muscle covering the keel bone, helping assess nutritional status. On a scale from 1 (emaciated) to 5 (obese), a score of 3 is considered ideal for most wild birds. A sharp, protruding keel suggests muscle wasting, while excessive fat accumulation may impair flight performance.

In conservation biology, monitoring changes in chest muscle mass across populations can reveal broader environmental stressors, such as habitat degradation, food scarcity, or climate change impacts on migration energetics. For example, declining body condition in migratory shorebirds has been linked to the loss of stopover sites where they refuel before long oceanic crossings.

How to Observe the Bird Chest in the Wild

To effectively study the bird chest in live specimens, consider the following practical tips:

- Use binoculars or spotting scopes: Focus on the ventral profile, especially when birds are perched sideways or in flight.

- Observe at dawn or dusk: Many birds engage in display behaviors during these times, making chest inflation more visible.

- Note posture changes: Aggressive, mating, or defensive postures often involve chest exposure.

- Compare individuals: Look for differences in chest depth among juveniles, adults, males, and females.

- Photograph for later analysis: Side-profile images allow for comparative studies over time.

When conducting surveys or citizen science projects (like eBird or Project FeederWatch), recording observations about body shapeâincluding chest prominenceâcan contribute valuable data to ornithological research.

Common Misconceptions About the Bird Chest

Several myths persist regarding the bird chest:

- Myth: All birds have large, visible chests.

Fact: Flightless and small passerine birds often have minimal chest projection. - Myth: A bigger chest always means better health.

Fact: Excessive fat deposits can mask poor muscle tone and reduce fitness. \li>Myth: The bird chest is mostly bone. - Myth: Only male birds show off their chests.

Fact: Both sexes may use chest displays, though males often do so more frequently during breeding.

Fact: It is primarily composed of muscle supported by a central keel structure.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What does a bird's chest tell us about its ability to fly?

- The size and muscle development of a bird's chest directly correlate with its flight capacity. Stronger, deeper chests support more powerful and sustained flight.

- Can you see the bird chest through feathers?

- Yes, experienced observers can discern the outline of the chest under feathers, especially in good light or when the bird is in motion or displaying.

- Do female birds have the same chest structure as males?

- Anatomically, yes. However, males may appear to have more prominent chests due to behavioral displays or slight sexual dimorphism in muscle mass.

- Why do some birds inflate their chests?

- Chest inflation is typically a social signalâused in courtship, aggression, or thermoregulationâto appear larger and more dominant.

- Is the bird chest the same as the crop?

- No. The crop is a pouch in the esophagus used for storing food, located near the base of the neck. The bird chest refers to the pectoral muscles and keel involved in flight.

In summary, understanding what a bird chest is goes beyond simple anatomyâit connects biomechanics, ecology, behavior, and even cultural symbolism. From enabling the miracle of flight to serving as a canvas for communication, the bird chest stands as a testament to natureâs engineering prowess. Whether viewed through a scientific lens or appreciated in the wild, this remarkable feature deepens our connection to the avian world.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4