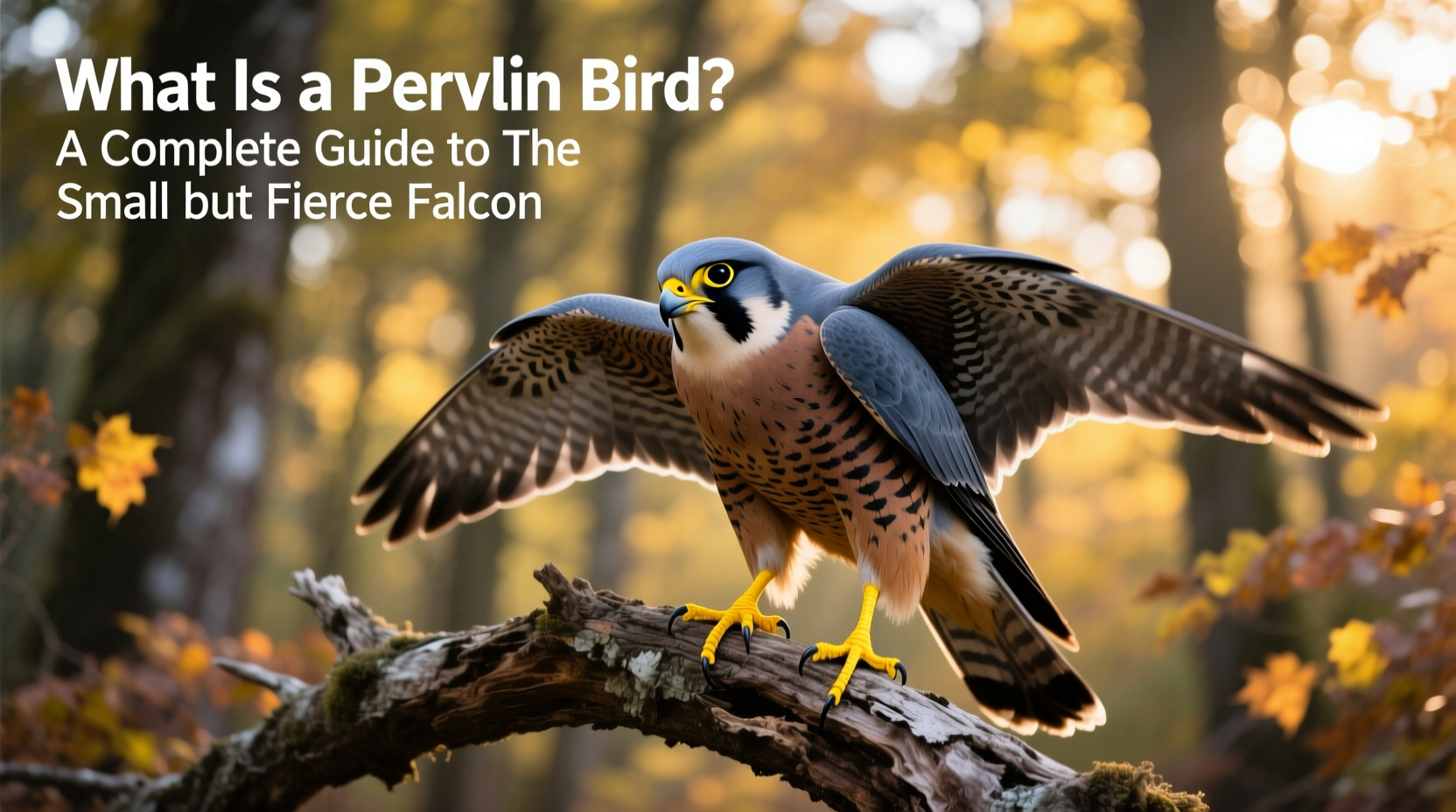

A merlin bird is a small but powerful falcon species known scientifically as Falco columbarius, renowned for its speed, agility, and fierce hunting behavior despite its compact size. Often described as a 'pocket predator' among raptors, the merlin is a widespread bird of prey found across North America, Europe, and Asia. This medium-sized falcon belongs to the family Falconidae and exhibits striking sexual dimorphism, with males and females differing in both coloration and size. If you're wondering what is a merlin bird and how it compares to other falcons like the peregrine or kestrel, this comprehensive guide will explore its physical characteristics, habitat preferences, migration patterns, ecological role, and even its symbolic meaning in various cultures.

Physical Characteristics and Identification

The merlin is a stocky, short-winged falcon that typically measures between 9 to 12 inches (23–30 cm) in length, with a wingspan ranging from 20 to 27 inches (51–69 cm). It weighs anywhere from 5.6 to 8.5 ounces (160–245 grams), making it slightly larger than the American kestrel but significantly smaller than the peregrine falcon.

Merlins exhibit three primary color morphs depending on their geographic location: taiga, prairie, and Pacific. The taiga merlin (F. c. columbarius) is the most widespread in North America and features dark gray upperparts with barred underparts. Females tend to be browner, while males have a bluish-gray back and orange-tinted underparts. The prairie merlin (F. c. richardsonii) has a pale, almost white underside with heavy barring, giving it a ghostly appearance in flight. The Pacific merlin (F. c. suckleyi) is darker overall, nearly black in some cases, especially in coastal British Columbia and Alaska.

One of the easiest ways to identify a merlin in flight is by its rapid wingbeats and low, direct flight path just above treetops or open fields. Unlike the hovering behavior of kestrels, merlins rely on surprise attacks, chasing down prey in swift pursuit. Their calls are high-pitched and repetitive—often described as a sharp kik-kik-kik-kik—frequently heard during territorial disputes or nesting season.

Habitat and Geographic Range

Merlins are highly adaptable birds that inhabit a wide range of environments, from boreal forests and tundra edges to grasslands, coastal dunes, and even urban areas. During the breeding season, they are primarily found in northern regions, including Canada, Alaska, Scandinavia, and Siberia. These habitats provide ample cover for nesting and abundant populations of small birds—their preferred prey.

In winter, many merlin populations migrate southward into the United States, southern Europe, and parts of Asia. Some individuals remain year-round in milder climates, particularly along the Pacific Coast and in the UK. Urban adaptation has been increasingly observed, with merlins nesting on skyscrapers and hunting pigeons in city parks—a behavior similar to peregrine falcons.

| Morph Type | Region | Coloration | Size Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taiga Merlin | Northern North America, Canada | Gray male, brown female; barred underparts | Medium |

| Prairie Merlin | Great Plains, central U.S. | Pale body, heavy barring | Slightly larger |

| Pacific Merlin | Coastal Pacific Northwest | Dark to blackish plumage | Largest subspecies |

Diet and Hunting Behavior

Merlins are carnivorous predators whose diet consists mainly of small birds such as sparrows, finches, larks, and shorebirds. They are also known to consume large insects, bats, and occasionally small mammals like voles. What sets the merlin apart from other raptors is its aggressive, fast-paced hunting style. Rather than soaring at great heights like eagles or using thermal currents extensively, merlins often fly close to the ground, using terrain and vegetation for cover before launching sudden aerial ambushes.

This 'hit-and-run' strategy allows them to catch prey off guard. They rarely scavenge and almost never hover like kestrels. Instead, they rely on speed and maneuverability, reaching bursts of up to 40 mph (64 km/h) when diving after prey. Their short, pointed wings and long tail give them exceptional control in tight spaces, enabling them to weave through trees and shrubs during chases.

Interestingly, merlins sometimes employ a technique called 'stooping,' though not as dramatically as peregrines. They may chase birds in level flight rather than from a high perch, using persistence and surprise over sheer velocity.

Breeding and Reproduction

The breeding season for merlins begins in late spring, typically between May and July, depending on latitude. Unlike many raptors, merlins do not build their own nests. Instead, they are opportunistic nesters, commonly taking over abandoned crow, magpie, or hawk nests located in coniferous or mixed woodlands. In more open landscapes, they may use rock crevices or even ground sites in treeless tundra.

The female lays 3 to 5 eggs, which she incubates for about 28 to 32 days while the male provides food. Chicks hatch covered in white down and are entirely dependent on parental care. Both parents feed the young, which fledge after approximately 25 to 30 days. Even after fledging, juveniles remain near the nest site for several weeks, learning to hunt under parental supervision.

Nest site fidelity varies; some pairs return to the same area annually, while others relocate based on prey availability and human disturbance. Nesting success can be affected by predation (from owls, raccoons, or larger raptors), weather conditions, and habitat fragmentation.

Migration Patterns and Seasonal Movements

Merlins are partial migrants, meaning that while some populations are resident year-round, others undertake significant seasonal migrations. Northern breeders in Canada and Alaska travel thousands of miles to wintering grounds in the southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America. Migration typically occurs from September through November in the fall and March through May in the spring.

During migration, merlins follow major flyways, including the Atlantic, Mississippi, and Pacific coasts. They are often seen along coastlines, mountain ridges, and large lakes where rising thermals assist their flight. Birdwatchers frequently spot them during hawk watches at sites like Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania or Cape May in New Jersey.

Tracking studies using satellite telemetry have shown that individual merlins may follow consistent routes each year, stopping at familiar refueling points. However, younger birds tend to be more variable in their paths, suggesting a learning component to navigation.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

The merlin has held symbolic importance in various cultures throughout history. In medieval Europe, it was a favored bird among noblewomen for falconry due to its manageable size and spirited temperament. Known as the 'lady's hawk,' the merlin was associated with grace, independence, and quiet strength. Its use in falconry dates back to at least the 12th century, particularly in France, England, and Scandinavia.

In modern symbolism, the merlin represents focus, precision, and resilience. Some Native American traditions view the merlin as a messenger between worlds, embodying keen perception and swift action. Its ability to thrive in diverse environments—from Arctic tundra to bustling cities—makes it a symbol of adaptability and survival.

In literature and art, the merlin often appears as a metaphor for vigilance and determination. Poets and naturalists alike have praised its no-nonsense hunting style and fearless nature, contrasting it with the more flamboyant peregrine falcon.

Conservation Status and Threats

The merlin is currently listed as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), thanks to its broad distribution and stable population trends. However, localized threats persist. Habitat loss due to deforestation, wetland drainage, and urban expansion can reduce nesting and foraging opportunities.

Pesticide use, particularly legacy chemicals like DDT, historically impacted merlin populations by thinning eggshells and reducing reproductive success. While DDT has been banned in many countries, newer pesticides and rodenticides still pose risks through bioaccumulation in the food chain.

Climate change may also affect merlin distribution in the long term. Warming temperatures could shift breeding ranges northward, potentially leading to competition with other raptors or mismatches in prey availability. On the positive side, increasing urbanization has created new niches for merlins, especially in cities where pigeon populations offer a reliable food source.

How to Observe Merlins: Tips for Birdwatchers

Spotting a merlin in the wild can be a thrilling experience for birdwatchers. Here are practical tips to increase your chances:

- Look in open areas: Check grasslands, marshes, coastal dunes, and agricultural fields, especially during migration seasons.

- Scan for fast, low flight: Merlins often fly just above the ground or treetops with rapid wingbeats and minimal gliding.

- Listen for calls: Their sharp, staccato kik-kik-kik call is distinctive and often precedes visual detection.

- Use binoculars or spotting scopes: Due to their small size and speed, optical aids are essential for proper identification.

- Visit hawk watch sites: During fall migration, head to established observation points along major flyways.

- Compare with similar species: Differentiate merlins from sharp-shinned hawks (slimmer, longer tail) and peregrine falcons (larger, different flight pattern).

Photographing merlins requires patience and quick reflexes. Use a telephoto lens (300mm or longer) and set your camera to continuous autofocus and burst mode to capture their rapid movements.

Common Misconceptions About Merlin Birds

Several myths surround the merlin. One common misconception is that it is simply a 'small peregrine falcon.' While they are closely related, merlins differ significantly in behavior, habitat preference, and hunting technique. Another myth is that merlins are rare. In reality, they are fairly common across their range but often overlooked due to their secretive nature and fast flight.

Some people confuse merlins with accipiters like the sharp-shinned hawk. Key distinguishing features include the merlin’s broader wings, squarer tail, and more direct flight. Additionally, merlins lack the accipiter’s characteristic flap-flap-glide flight pattern.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- What does a merlin bird look like?

- A merlin is a small, robust falcon with short wings and a long tail. Coloration varies by subspecies but generally includes gray, brown, or dark plumage with barred underparts. Males have bluish-gray backs, while females are browner.

- Where can I see a merlin bird?

- Merlins can be found in open woodlands, grasslands, coastal areas, and increasingly in cities. Look for them during migration at hawk watch sites or in winter across much of the United States and southern Canada.

- Is a merlin a type of hawk?

- No, a merlin is not a hawk. It is a true falcon (genus Falco), distinguished by its pointed wings, notched beak, and faster, more direct flight compared to hawks.

- Do merlins migrate?

- Yes, many merlin populations migrate seasonally. Northern breeders move south to the U.S., Mexico, and Central America in winter, while some coastal and temperate populations remain resident year-round.

- Can merlins be kept as pets?

- No, merlins cannot be kept as pets. They are wild raptors protected under laws such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in the U.S. Only licensed falconers may possess them for hunting under strict regulations.

In conclusion, understanding what is a merlin bird reveals a fascinating blend of biological prowess and cultural resonance. From its lightning-fast hunts to its historical role in falconry, the merlin stands out as a dynamic and resilient member of the avian world. Whether you're a seasoned birder or a curious observer, learning to identify and appreciate this agile raptor enriches our connection to nature’s intricate web.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4