All birds are members of the class Aves, a diverse group of warm-blooded vertebrates characterized by feathers, beaks, the ability to lay hard-shelled eggs, and—most notably—for their capacity for flight, although not all species can fly. This fundamental understanding of what is all birds reveals a unifying biological framework that distinguishes them from mammals, reptiles, and other animal classes. The phrase 'what is all birds' may seem broad, but in scientific and ecological contexts, it refers to the shared evolutionary traits and taxonomic classification that define every avian species on Earth. From the tiniest hummingbird to the towering ostrich, all birds share key anatomical and physiological features such as a lightweight skeleton, efficient respiratory system, and high metabolic rate.

Defining Characteristics of Birds

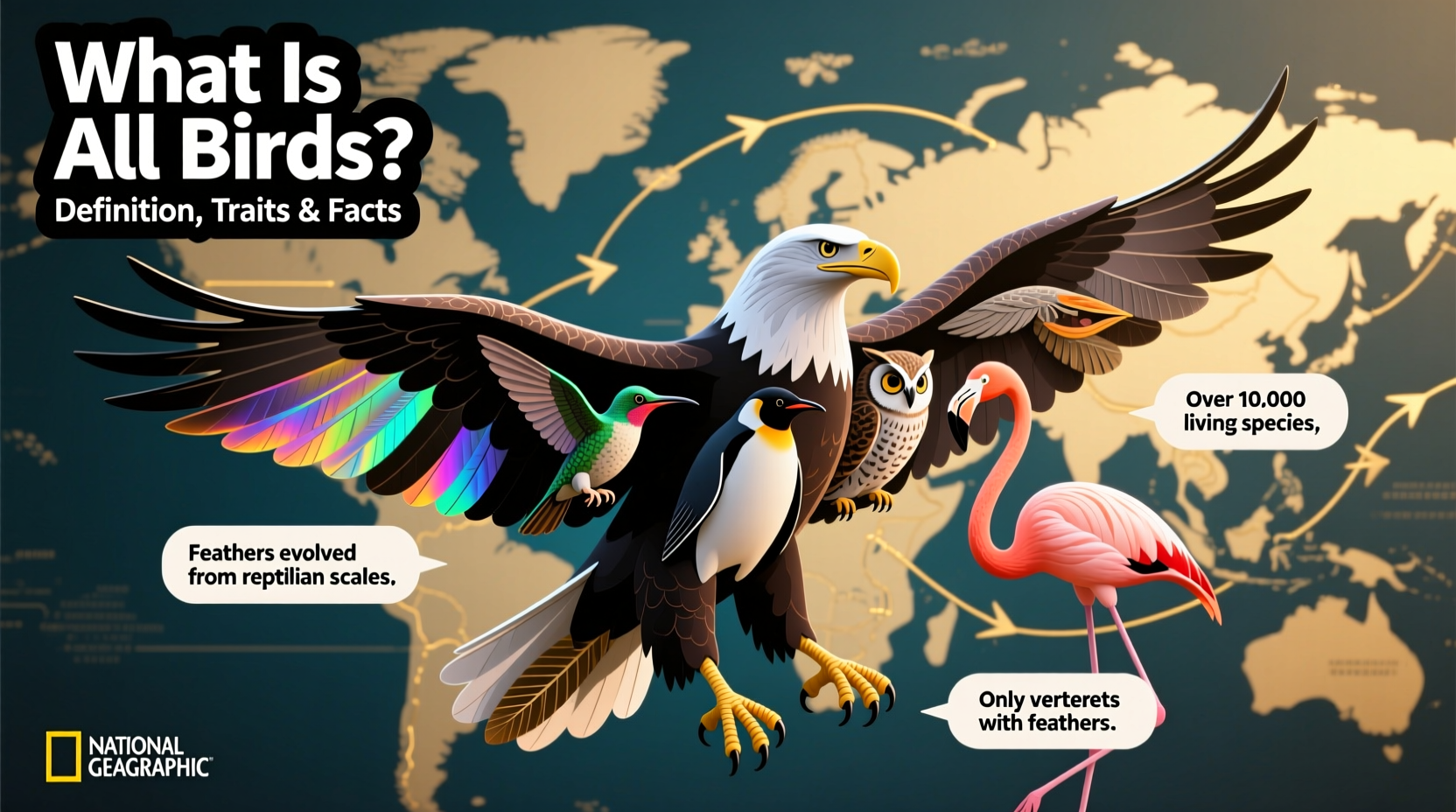

The biological definition of birds centers around several unmistakable traits. First and foremost, feathers are exclusive to birds and serve multiple functions including insulation, display, and flight. No other animal group possesses true feathers, making this feature a definitive marker of avian identity. Feathers evolved from reptilian scales and have undergone significant specialization across species—from the stiff flight feathers of eagles to the downy insulation of penguins.

Another defining trait is the presence of a beak or bill, which lacks teeth in modern birds (though ancient species like Archaeopteryx did have them). Beaks are highly adapted to diet and environment: crossbills use theirs to extract seeds from cones, while pelicans employ large pouches to scoop fish. These adaptations reflect the evolutionary success of birds across nearly every terrestrial habitat.

Birds are also endothermic (warm-blooded), allowing them to maintain a constant internal temperature regardless of external conditions. This enables sustained activity levels and supports the high energy demands of flight. Coupled with this is a four-chambered heart, similar to mammals, which efficiently separates oxygenated and deoxygenated blood.

Reproduction in birds involves laying amniotic eggs with hard shells, typically calcium-based. Most species exhibit parental care, with incubation and feeding behaviors varying widely—from altricial hatchlings that require extensive care to precocial young that can walk or swim shortly after hatching.

Evolutionary Origins: From Dinosaurs to Modern Avians

One of the most profound discoveries in paleontology is that birds are direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs. Fossils such as Archaeopteryx, discovered in the 19th century, show a mosaic of reptilian and avian traits—teeth, long bony tails, and feathered wings. This transitional fossil provided early evidence linking birds to dinosaurs.

Modern genetic and morphological studies confirm that birds belong within the dinosaur clade Maniraptora. In fact, many scientists consider birds to be the only living lineage of dinosaurs. This means that when we observe a sparrow flitting through a backyard or a hawk soaring above mountains, we are witnessing the continued existence of dinosaurs in a modified form.

The mass extinction event 66 million years ago wiped out non-avian dinosaurs, but small, feathered ancestors of modern birds survived. Over millions of years, they diversified into over 10,000 known species today, occupying niches ranging from deep ocean dives (penguins) to high-altitude migrations (bar-headed geese).

Biodiversity and Classification of Bird Species

What is all birds if not an incredibly varied assemblage of life? The class Aves is divided into approximately 40 orders, each representing a major evolutionary branch. Some of the most well-known include:

- Passeriformes – Perching birds, including sparrows, robins, and crows (over 5,000 species)

- Falconiformes – Birds of prey such as hawks, eagles, and falcons

- Strigiformes – Owls, known for nocturnal hunting and silent flight

- Psittaciformes – Parrots and cockatoos, famed for intelligence and vocal mimicry

- Anseriformes – Ducks, geese, and swans

- Sphenisciformes – Penguins, flightless seabirds adapted to aquatic life

This diversity reflects adaptive radiation—where a single ancestor gives rise to multiple species suited to different environments. For example, Darwin’s finches in the Galápagos Islands evolved distinct beak shapes based on available food sources, illustrating natural selection in action.

| Order | Common Name | Key Traits | Example Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passeriformes | Perching Birds | Three toes forward, one back; complex songs | American Robin |

| Falconiformes | Raptors | Sharp talons, hooked beaks, keen vision | Bald Eagle |

| Strigiformes | Owls | Nocturnal, facial disks, silent flight | Great Horned Owl |

| Psittaciformes | Parrots | Zygodactyl feet, strong bills, vocal learners | Blue-and-Gold Macaw |

| Sphenisciformes | Penguins | Flightless, flipper-like wings, marine lifestyle | Emperor Penguin |

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Birds

Beyond biology, birds hold deep cultural, spiritual, and symbolic meanings across human societies. In many traditions, they represent freedom, transcendence, and the soul’s journey. For instance:

- In Native American cultures, the eagle symbolizes strength, courage, and divine connection.

- In Christianity, the dove represents peace and the Holy Spirit.

- In ancient Egypt, the Bennu bird (a precursor to the phoenix) embodied rebirth and immortality.

- In Chinese symbolism, cranes signify longevity and wisdom.

Birds frequently appear in literature and art as metaphors for aspiration and escape. Poets like Emily Dickinson and Alfred Lord Tennyson used birds to explore themes of mortality and beauty. Even in modern media, characters like Big Bird or Hedwig carry emotional resonance rooted in our collective fascination with avian life.

Are Birds Mammals? Clarifying Common Misconceptions

A frequent question related to 'what is all birds' is whether birds are mammals. The answer is no. While both groups are warm-blooded and have four-chambered hearts, birds differ fundamentally in reproduction (laying eggs vs. live birth), body covering (feathers vs. hair/fur), and skeletal structure (lightweight bones adapted for flight).

Another misconception is that flight defines all birds. However, several species—including ostriches, emus, kiwis, and penguins—are flightless. Their inability to fly does not exclude them from being birds; rather, it illustrates evolutionary adaptation to specific environments where flight was less advantageous than running or swimming.

Practical Guide to Birdwatching: Tips for Beginners

Understanding what is all birds isn’t just academic—it can enrich outdoor experiences. Birdwatching (or birding) is a growing hobby that combines nature appreciation with scientific observation. Here are practical tips for getting started:

- Get a field guide or app: Resources like the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Merlin Bird ID app help identify species by sight, sound, or location.

- Use binoculars: A good pair (8x42 magnification recommended) enhances visibility without added weight.

- Visit local hotspots: Parks, wetlands, and nature reserves often host diverse species. Check eBird.org for real-time sightings.

- Listen to calls and songs: Many birds are heard before seen. Learning common sounds improves detection.

- Keep a journal: Record species, behaviors, weather, and locations to track patterns over time.

- Respect wildlife: Maintain distance, avoid playback calls excessively, and follow local conservation guidelines.

Timing matters: early morning hours (dawn to mid-morning) are peak activity periods for most birds due to cooler temperatures and higher insect availability.

Conservation Challenges Facing Birds Today

Despite their adaptability, birds face unprecedented threats. Habitat loss, climate change, pollution, and invasive species contribute to population declines worldwide. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), over 1,400 bird species are threatened with extinction.

Notable examples include:

- The Kakapo, a flightless parrot from New Zealand, reduced to fewer than 250 individuals due to predation by introduced mammals.

- The North American migratory songbirds, whose numbers have dropped by nearly 3 billion since 1970, according to a 2019 study published in Science.

- The Vultures of South Asia, decimated by diclofenac poisoning from livestock carcasses.

Individuals can support bird conservation by creating bird-friendly yards (native plants, avoiding pesticides), participating in citizen science projects like the Christmas Bird Count, and supporting organizations like Audubon Society or BirdLife International.

Regional Variations in Bird Diversity

Bird distribution varies significantly by region. Tropical zones near the equator—such as the Amazon rainforest, Congo Basin, and Southeast Asian jungles—host the highest avian biodiversity due to stable climates and abundant resources. In contrast, polar regions have fewer species, though some like the Arctic Tern undertake extraordinary migrations between hemispheres.

Urbanization affects bird communities differently depending on geography. In North America, generalist species like pigeons and starlings thrive in cities, while native specialists decline. In Europe, urban green spaces support higher bird diversity due to intentional planning and preservation efforts.

Migration patterns also vary regionally. North American warblers travel thousands of miles between breeding grounds in Canada and wintering areas in Central and South America. Meanwhile, Australian birds tend to be more sedentary, with limited seasonal movements.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are all birds capable of flight?

- No, not all birds can fly. Flightless birds include ostriches, emus, cassowaries, kiwis, and penguins. These species evolved in environments where flight was unnecessary or disadvantageous.

- How many bird species exist worldwide?

- There are approximately 10,000 to 11,000 recognized bird species globally, with new species still being discovered, especially in remote tropical regions.

- Do birds sleep?

- Yes, birds do sleep, often with one hemisphere of the brain awake (unihemispheric slow-wave sleep), particularly during migration or in vulnerable environments.

- What makes birds different from reptiles?

- While birds evolved from reptiles, they are distinguished by feathers, endothermy, more efficient lungs, and advanced neurological development, especially in social and vocal learning abilities.

- Can birds recognize humans?

- Yes, many bird species, especially corvids (crows, ravens) and parrots, can recognize individual human faces and voices, demonstrating complex cognitive processing.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4