Bird flu in chickens, also known as avian influenza, is a highly contagious viral infection caused by influenza A viruses that primarily affect poultry and wild birds. Understanding what is bird flu in chickens is essential for farmers, backyard flock owners, and public health officials alike, as outbreaks can lead to massive economic losses and, in rare cases, pose zoonotic risks to humans. The most virulent strain, H5N1, has been responsible for numerous poultry culls worldwide and continues to circulate in both domestic and wild bird populations.

Understanding Avian Influenza: The Biology Behind Bird Flu

Avian influenza viruses belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family and are categorized based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 16 H subtypes and 9 N subtypes, but the most concerning for poultry are H5 and H7. These viruses are further classified into low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) and high pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). While LPAI may cause mild symptoms or go unnoticed, HPAIâparticularly H5N1âcan spread rapidly through chicken flocks, causing severe illness and mortality rates approaching 90â100% within days.

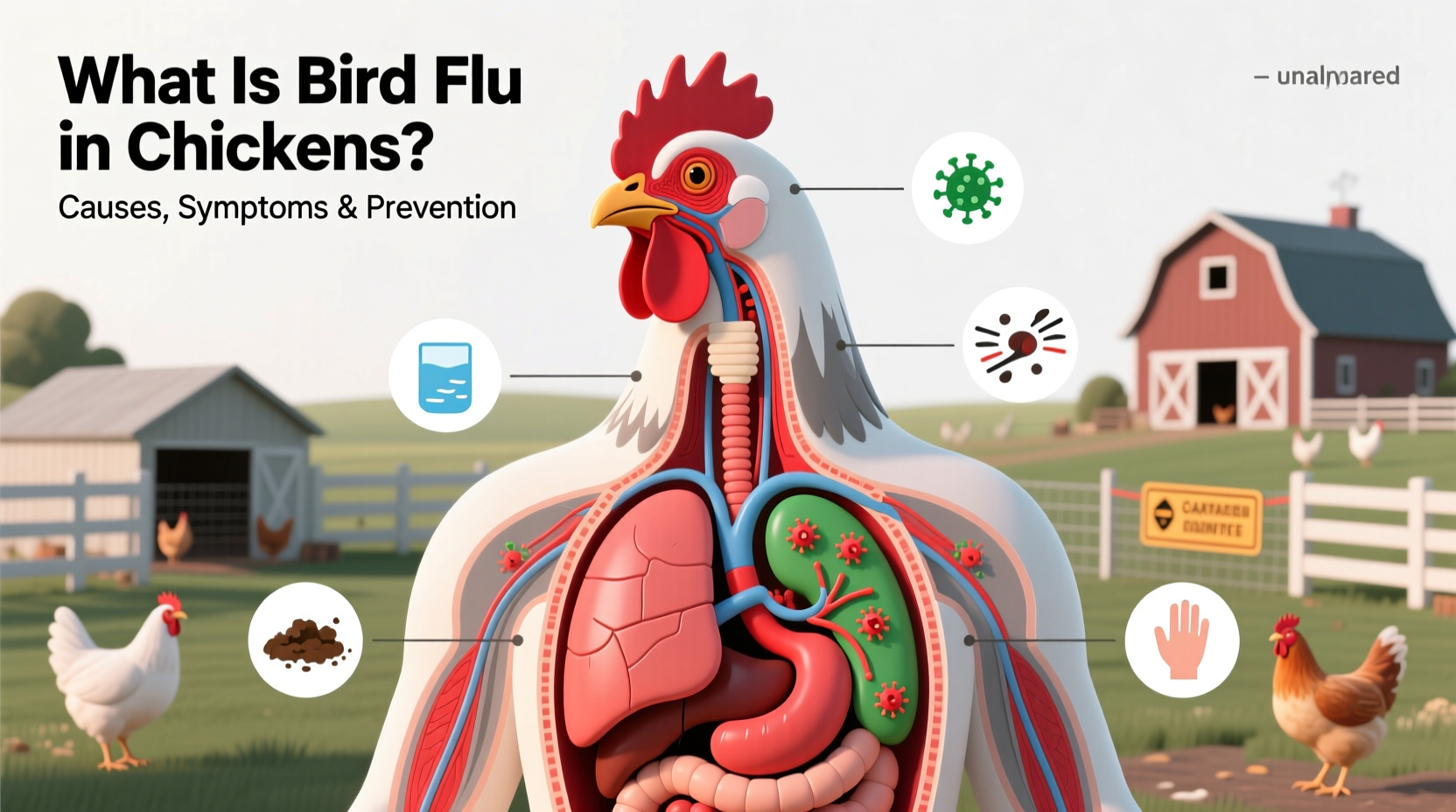

The virus spreads through direct contact with infected birds, contaminated feces, respiratory secretions, feed, water, equipment, and even clothing or footwear of handlers. Wild migratory birds, especially waterfowl like ducks and geese, often carry the virus asymptomatically and introduce it into commercial or backyard poultry operations during migration seasons.

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Chickens

Recognizing early signs of bird flu in chickens is critical for containment. Clinical manifestations vary depending on the strain but commonly include:

- Sudden death without prior symptoms

- Decreased food and water intake

- Ruffled feathers and lethargy

- Swelling of the head, eyelids, comb, wattles, and hocks

- Purple discoloration of wattles, combs, and legs

- Soft-shelled or misshapen eggs

- Drop in egg production

- Neurological signs such as tremors or lack of coordination

- Nasal discharge, coughing, and sneezing

In milder cases caused by LPAI strains, symptoms might be subtleâsuch as reduced appetite or minor respiratory issuesâmaking surveillance challenging without laboratory testing.

Transmission Pathways and Risk Factors

Bird flu transmission in chickens occurs through multiple vectors. Key risk factors include:

- Proximity to wild birds: Farms near wetlands or migratory routes are at higher risk.

- Poor biosecurity: Shared equipment, unclean boots, or visitors can introduce pathogens. \li>Movement of live birds: Transporting infected poultry between markets or farms accelerates spread.

- Contaminated water sources: Ponds or open water tanks exposed to wild bird droppings serve as infection hubs.

- Live bird markets: High-density environments where birds from various sources mix increase transmission likelihood.

Seasonality plays a role; outbreaks often spike during fall and winter when migratory birds travel south, increasing contact opportunities with domestic flocks.

Economic and Public Health Impact

An outbreak of bird flu in chickens can devastate local and national economies. Entire flocks are typically culled to prevent further spread, leading to supply chain disruptions, increased egg and poultry prices, and export restrictions. For example, the 2022â2023 H5N1 outbreak in the United States led to the depopulation of over 58 million birds across 47 states, marking it one of the worst animal health crises in U.S. history.

While human infections remain rare, they do occurâusually among individuals with close, prolonged contact with infected birds. Symptoms in humans range from conjunctivitis to severe respiratory disease and, in some cases, death. The World Health Organization monitors these zoonotic events closely due to concerns about potential pandemic strains emerging if the virus gains efficient human-to-human transmissibility.

| Strain Type | Pathogenicity | Typical Symptoms in Chickens | Zoonotic Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| H5N1 (HPAI) | High | Sudden death, swelling, neurological signs | Moderate (rare human cases) |

| H7N9 (HPAI) | High | Respiratory distress, decreased laying | Higher (more human cases reported) |

| H9N2 (LPAI) | Low | Mild respiratory signs, slight drop in production | Low, but can reassort with other viruses |

Diagnosis and Laboratory Testing

Confirming bird flu in chickens requires laboratory analysis. Common diagnostic methods include:

- RT-PCR (Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction): Detects viral RNA quickly and accurately.

- Virus isolation: Grows the virus in embryonated eggs for definitive identification.

- Serological tests: ELISA tests detect antibodies indicating past exposure.

Farmers suspecting an outbreak must report it immediately to veterinary authorities. Rapid response teams collect samples from sick or dead birds for analysis at certified labs. Early detection enables faster containment and reduces the risk of regional spread.

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures

Preventing bird flu in chickens hinges on strict biosecurity protocols. Key strategies include:

- Isolate poultry: Keep domestic birds separated from wild birds using netted enclosures or indoor housing.

- Control access: Limit visitors and require protective clothing for workers.

- Sanitize equipment: Regularly clean coops, feeders, and waterers with disinfectants effective against enveloped viruses.

- Monitor health daily: Watch for behavioral changes or mortality spikes.

- Avoid sharing tools: Do not loan out crates, cages, or vehicles used around poultry.

- Quarantine new birds: Isolate incoming chickens for at least 30 days before integrating them into existing flocks.

Backyard flock owners should avoid feeding kitchen scraps that may have contacted raw poultry products and ensure children wash hands after handling birds.

Vaccination: Pros, Cons, and Global Practices

Vaccination against bird flu exists but is controversial. Some countries, including China and parts of Southeast Asia, use vaccines routinely to protect large poultry industries. However, vaccination does not eliminate the virusâit only reduces symptoms and shedding. This creates challenges:

- Vaccinated birds may still carry and transmit the virus silently.

- Differentiating infected from vaccinated animals (DIVA) requires specialized testing.

- Vaccines must match circulating strains, which evolve rapidly.

In contrast, the United States and European Union generally avoid routine vaccination, opting instead for surveillance, rapid culling, and movement controls during outbreaks. Vaccines are stockpiled for emergency use only.

Global Surveillance and Reporting Systems

International cooperation is vital in tracking bird flu in chickens. Organizations like the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintain global databases and issue alerts when new strains emerge. Countries are encouraged to report outbreaks transparently to enable timely interventions.

Satellite tracking of migratory birds, genomic sequencing of virus isolates, and real-time data sharing help predict hotspots and guide preventive actions. Farmers and veterinarians can access up-to-date information through national agricultural departments and international networks.

What to Do During an Outbreak

If you suspect bird flu in your flock:

- Do not move any birds, eggs, manure, or equipment off the property.

- Contact your veterinarian or state animal health authority immediately.

- Isolate sick birds and minimize human contact.

- Wear personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, masks, and goggles when handling birds.

- Follow official guidance regarding depopulation, disposal, cleaning, and downtime before restocking.

After depopulation, thorough disinfection of barns, soil (if applicable), and equipment is required. A downtime period of at least 21 days is typically mandated before introducing new birds.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu in Chickens

Several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Misconception: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and eggs pose no risk. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F). - Misconception: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Ducks, turkeys, quail, and many wild species are also susceptible. - Misconception: All bird flu strains are deadly to humans.

Fact: Most strains do not infect people. Human cases are rare and usually linked to intense exposure.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Ongoing research focuses on developing universal avian influenza vaccines, improving rapid diagnostics, and enhancing early warning systems using AI and environmental sampling. Scientists are also studying how climate change affects bird migration patterns and virus persistence in the environment, which could influence future outbreak dynamics.

Genomic surveillance helps track mutations that could increase transmissibility or virulence. Public awareness campaigns and farmer education programs remain crucial in reducing risks associated with bird flu in chickens.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can humans catch bird flu from eating chicken?

- No, consuming properly cooked chicken or eggs does not transmit bird flu. Always cook poultry to an internal temperature of 165°F (74°C) for safety.

- How fast does bird flu spread among chickens?

- In high-pathogenicity outbreaks, the virus can spread through a flock within 24â48 hours, often resulting in sudden mass deaths.

- Is there a cure for bird flu in chickens?

- There is no treatment. Infected flocks are usually depopulated to stop the spread. Antivirals are not used in poultry.

- Are backyard chickens at risk of bird flu?

- Yes, especially if they have outdoor access or come into contact with wild birds. Strict biosecurity is essential for small flocks.

- How often do bird flu outbreaks occur?

- Outbreaks happen annually, with larger epidemics every few years. H5N1 has been circulating globally since the late 1990s, with recurring waves.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4