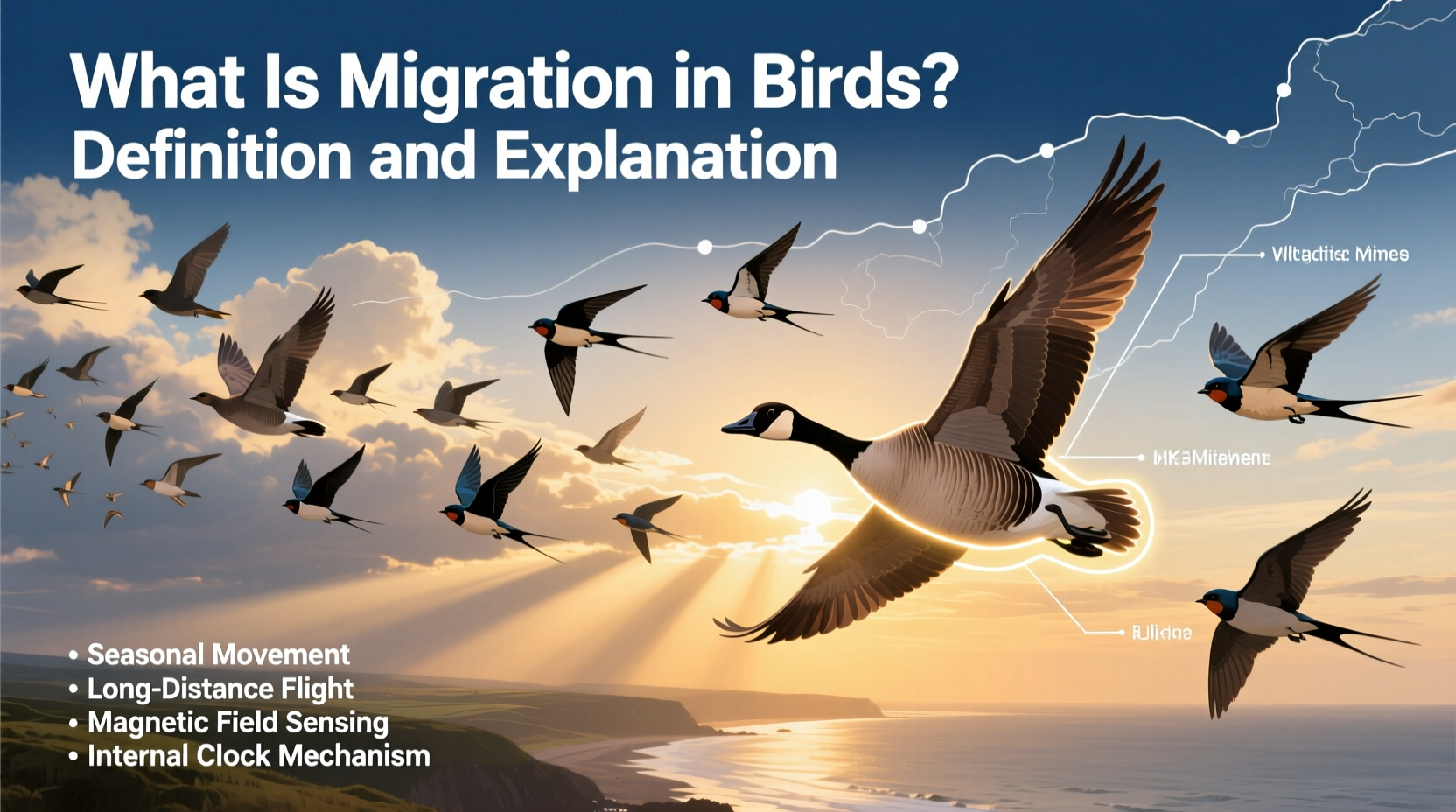

Bird migration is the regular, seasonal movement of bird species between breeding and wintering grounds, a phenomenon driven by changes in food availability, daylight, and temperature. This natural behavior, known as avian migration, ensures survival and reproductive success across diverse climates. Every year, millions of birds undertake incredible journeysâsome spanning thousands of milesâguided by innate navigation systems involving the sun, stars, Earth's magnetic field, and environmental cues. Understanding what is migration in birds reveals not only biological necessity but also evolutionary brilliance.

The Biological Basis of Bird Migration

At its core, bird migration is an adaptive strategy shaped by evolution. Birds migrate to exploit favorable environments for feeding and reproduction. The primary trigger for migration is photoperiodâthe length of daylightâwhich influences hormonal changes that prepare birds physiologically for long flights. These preparations include fat accumulation, muscle strengthening, and even partial organ shrinkage to reduce weight.

Species such as the Arctic Tern exemplify extreme endurance, traveling up to 44,000 miles annually from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back. In contrast, some North American warblers may fly only several hundred miles but still face significant challenges like crossing the Gulf of Mexico on nonstop flights lasting over 24 hours.

Migratory patterns are often genetically encoded. Young birds making their first journey do so without guidance from experienced adults in many species, relying instead on internal compasses and inherited flight routes. Scientists have demonstrated this through experiments with captive-reared birds showing directional preferences during migration seasons.

Types of Migration Patterns

Bird migration varies widely in distance, timing, and route. Researchers classify migrations into several types:

- Complete migration: All members of a population leave the breeding area.

- Partial migration: Only some individuals (often younger or female birds) migrate while others remain. \li>Leapfrog migration: Northern populations migrate farther south than southern ones, effectively "leapfrogging" over them.

- Irruptive migration: Irregular movements caused by food shortages rather than seasonal change, seen in species like crossbills and snowy owls.

These variations reflect ecological pressures and resource distribution. For example, irruptive migration cannot be predicted annually, unlike fixed schedules followed by ducks or geese.

Navigation Mechanisms: How Birds Find Their Way

One of the most fascinating aspects of what is migration in birds lies in how they navigate vast distances with remarkable precision. Multiple sensory systems contribute:

- Celestial cues: Birds use the position of the sun during the day and star patterns at night. Experiments show that depriving birds of starlight disrupts orientation.

- Magnetic sensing: Evidence suggests birds detect Earthâs magnetic field via specialized receptors in their eyes or beaks, possibly involving quantum-level processes in cryptochrome proteins.

- Landmarks: Rivers, coastlines, mountain ranges, and even urban lights help birds orient during daytime or nocturnal flights.

- Olfactory cues: Some seabirds, like petrels, rely heavily on smell to locate nesting islands after months at sea.

Recent studies using miniaturized GPS trackers have revealed previously unknown stopover sites and detours influenced by wind patterns and weather events. These tools are revolutionizing our understanding of migration pathways and conservation needs.

Seasonal Timing and Environmental Triggers

The timing of bird migration is tightly linked to environmental conditions. Spring migration typically occurs from late February through May in the Northern Hemisphere, when increasing daylight signals the return to breeding grounds. Fall migration spans August to November, allowing birds to reach warmer regions before food becomes scarce.

However, climate change is altering these patterns. Many species now initiate migration earlier in spring due to warmer temperatures and advanced insect emergence. While this flexibility can benefit some birds, mismatches between arrival times and peak food availability pose risks, especially for insectivorous species dependent on brief hatching periods.

For instance, European Pied Flycatchers arriving too late miss caterpillar peaks in forests, reducing chick survival rates. Such phenological shifts underscore the vulnerability of migratory systems to global warming.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance of Migration

Beyond biology, bird migration holds deep cultural resonance across human societies. In many traditions, the return of swallows to San Juan Capistrano or the flight of cranes over rural Asia symbolizes renewal, hope, and the passage of seasons.

In Native American lore, geese represent teamwork and communication, reflecting their V-formation flying style. Similarly, in Chinese poetry, migrating wild geese evoke themes of longing and separation, often used metaphorically for exiled scholars or absent lovers.

Religious texts also reference migration. The Quran mentions Solomonâs correspondence with the Queen of Sheba and notes birdsâ orderly movements under divine command. These symbolic interpretations highlight humanityâs long-standing fascination with avian journeys as metaphors for spiritual or emotional transitions.

Conservation Challenges Facing Migratory Birds

Despite their resilience, migratory birds face growing threats. Habitat loss along flywaysâespecially wetlands, coastal zones, and tropical forestsâdisrupts critical stopover points where birds rest and refuel. Urban development, agricultural expansion, and deforestation compound these issues.

Collisions with buildings, communication towers, and wind turbines kill hundreds of millions of birds annually in North America alone. Light pollution disorients nocturnal migrants, leading to fatal exhaustion or crashes into illuminated structures.

Climate change further exacerbates risks by shifting habitat suitability and altering precipitation patterns. Species like the Red Knot, which depends on horseshoe crab eggs during a brief stop in Delaware Bay, suffer when spawning cycles fall out of sync with bird arrivals.

| Threat | Impact on Migratory Birds | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Habitat Loss | Reduces feeding and resting areas | Draining of wetlands in China affects spoon-billed sandpipers |

| Light Pollution | Disorients nocturnal migrants | Tower kills in Midwest U.S. during fall migration |

| Climate Shifts | Alters timing and food availability | Purple Martins arriving before insect emergence |

| Window Collisions | Major cause of bird mortality | Urban centers like Chicago report high collision rates |

How to Support Migratory Birds: Practical Tips for Observers

Individuals can play a role in protecting migratory species. Here are actionable steps:

- Participate in citizen science: Join programs like eBird or Project FeederWatch to contribute data on bird sightings and migration timing.

- Make windows safer: Apply decals, use netting, or install external screens to reduce reflections that attract birds.

- Turn off unnecessary lights: Especially during peak migration months (spring and fall), participate in Lights Out initiatives in cities.

- Plant native vegetation: Provide nectar, seeds, and shelter for migrating songbirds and pollinators.

- Avoid pesticides: Chemicals reduce insect populations essential for feeding chicks during breeding season.

Supporting protected areas and advocating for international agreements like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (U.S.) or the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA) strengthens legal frameworks for conservation.

Regional Differences in Migration Behavior

Migratory patterns differ significantly by region. In North America, four major flyways guide bird movements: Pacific, Central, Mississippi, and Atlantic. Each corridor follows geographic features like rivers or mountain ranges that aid navigation.

In Europe, many birds follow eastern and western routes around the Mediterranean, avoiding large water crossings. Meanwhile, Afro-Palearctic migrants travel between sub-Saharan Africa and Eurasia, facing desert crossings and hunting pressures in countries like Egypt and Lebanon.

Tropical regions see less dramatic latitudinal shifts but more altitudinal migration, where birds move up and down mountain slopes with seasonal changes. Andean hummingbirds, for example, descend to lower elevations during colder months.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Migration

Several myths persist about what is migration in birds:

- Myth: All birds migrate.

Reality: Many species, like cardinals or scrub jays, are non-migratory and remain in the same area year-round. - Myth: Birds migrate because it gets cold.

Reality: Cold itself isnât the main driver; lack of food is. Some birds thrive in freezing temperatures if food is available. - Myth: Migration happens overnight.

Reality: Most journeys involve multiple stops over weeks or months, not continuous flight. - Myth: Birds fly only during the day.

Reality: Over 70% of North American songbirds migrate at night to avoid predators and overheating.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What causes birds to start migrating?

- Changes in daylight trigger hormonal responses that prompt birds to feed more and prepare for flight. Food scarcity and temperature shifts reinforce the urge to move.

- How far do birds migrate?

- Distances vary: some travel just a few miles, while others, like the Arctic Tern, cover over 40,000 miles round-trip annually.

- Do all birds migrate south for winter?

- No. In the Southern Hemisphere, birds migrate northward. Others move east-west or altitudinally depending on regional climates.

- Can climate change affect bird migration?

- Yes. Warmer temperatures lead to earlier springs, causing some birds to migrate sooner. This can create mismatches with food sources.

- How can I observe bird migration?

- Visit key watchpoints during spring and fall, such as Cape May (NJ), Hawk Mountain (PA), or Point Pelee (ON). Use binoculars and field guides or apps like Merlin Bird ID.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4