The cloaca in birds is a single posterior opening that serves as the exit point for the digestive, urinary, and reproductive systems. Often referred to as the 'avian vent' or 'common chamber,' the cloaca is a defining anatomical feature of birds, playing a crucial role in waste elimination, mating, and egg-laying. Understanding what is cloaca in birds reveals not only key aspects of avian biology but also highlights evolutionary adaptations that distinguish birds from mammals. This multifunctional structure enables birds to maintain lightweight bodies—essential for flight—by consolidating multiple physiological processes into one efficient system.

Basic Anatomy of the Avian Cloaca

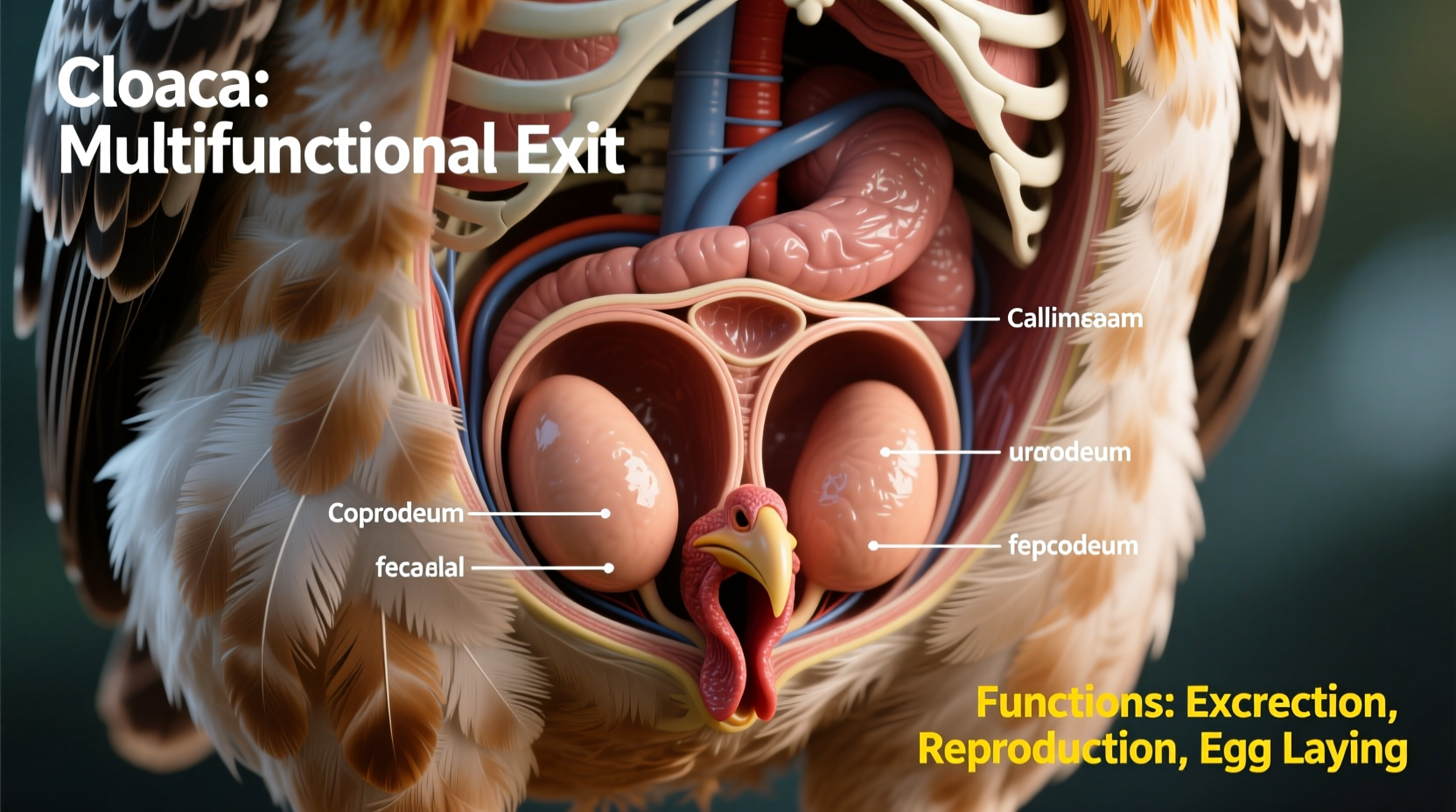

The cloaca is located at the base of the tail, just below the uropygial gland (preen gland) in most bird species. It is divided into three distinct chambers: the coprodeum, urodeum, and proctodeum.

- Coprodeum: The first chamber receives feces from the rectum. It acts as a temporary holding area before waste is expelled.

- Urodeum: This middle section connects to the ureters and genital ducts. In females, it receives the oviduct; in males, the vas deferens. It handles uric acid (the semi-solid form of nitrogenous waste) and reproductive cells.

- Proctodeum: The final chamber leads to the external opening. It stores waste temporarily and controls expulsion through muscular sphincters.

Unlike mammals, which have separate openings for urine, feces, and reproduction, birds rely on this unified structure. This adaptation reduces body weight and streamlines internal anatomy—critical advantages for flight efficiency.

Functions of the Cloaca in Birds

The cloaca performs several vital biological functions, making it central to avian survival and reproduction.

Digestive and Excretory Role

Birds do not produce liquid urine like mammals. Instead, they excrete nitrogenous waste in the form of uric acid, which combines with fecal matter in the cloaca. This mixture is expelled as a semi-solid white paste—commonly seen on car windshields or sidewalks. The cloaca reabsorbs water efficiently, helping birds conserve fluids, especially important during long flights or in arid environments.

Reproductive Function

In both male and female birds, the cloaca plays a pivotal role in reproduction. During mating, birds engage in a brief contact known as the 'cloacal kiss.' The male and female press their cloacas together, allowing sperm transfer from male to female without the need for external genitalia. This method is quick and minimizes exposure to predators.

In females, the egg passes through the oviduct and into the cloaca before being laid. The cloaca ensures that the egg does not come into contact with fecal material, reducing contamination risk—a remarkable feat given the shared pathway.

Immune and Microbial Regulation

Recent studies suggest the cloaca hosts a complex microbiome that contributes to immune function. Some birds, such as chickens and waterfowl, have lymphoid tissues associated with the cloaca (e.g., cloacal bursa), which are essential for B-cell development—an important part of the adaptive immune system.

Evolutionary Significance of the Cloaca

The presence of a cloaca is not unique to birds; it is also found in reptiles, amphibians, fish, and monotremes (like the platypus). This suggests an ancient evolutionary origin. In birds, the cloaca represents a streamlined solution to physiological challenges posed by flight.

By combining excretory and reproductive tracts into one opening, birds reduce internal complexity and body mass. This contrasts sharply with placental mammals, which evolved separate systems for greater control over reproduction and waste management.

Interestingly, despite lacking external genitalia, some bird species—such as ducks, geese, and swans—have evolved penises within the cloaca. These structures allow for internal fertilization in aquatic environments where a 'cloacal kiss' might be less reliable due to water displacement.

Cloaca Across Bird Species: Variations and Adaptations

While all birds possess a cloaca, its size, shape, and function can vary significantly across species depending on ecology and reproductive strategies.

| Bird Group | Cloacal Features | Special Adaptations |

|---|---|---|

| Passerines (e.g., sparrows) | Small, compact cloaca | Rapid cloacal kiss during mating; minimal external exposure |

| Anatidae (ducks, geese) | Larger, with erectile tissue | Internal penis-like structure for forced insemination in some species |

| Raptors (e.g., hawks) | Moderate size, muscular walls | Efficient waste expulsion during high-altitude flight |

| Flightless birds (e.g., ostrich) | Large and robust | Handles higher volume of fibrous plant waste |

These variations reflect how evolutionary pressures shape even internal anatomy. For example, ducks exhibit some of the most complex cloacal morphologies in the animal kingdom, with spiral-shaped vaginas and corkscrew penises—an evolutionary arms race driven by mating competition.

Cloaca in Avian Health and Disease

The cloaca is not just a functional organ—it can also be a site of medical concern. Cloacal disorders are relatively common in captive birds and may include:

- Prolapse: When the cloaca or parts of the oviduct protrude externally. Often caused by egg-binding, obesity, or chronic straining.

- Cloacal papillomas: Benign growths linked to viral infections, particularly in psittacine birds (parrots).

- Infections: Bacterial or fungal infections can occur, especially in birds with poor hygiene or compromised immunity.

- Impaction: Build-up of urates or feces, sometimes due to dehydration or diet issues.

Veterinarians often perform cloacal exams to assess overall health, check for parasites, or collect samples for DNA sexing or disease testing. In wild bird studies, researchers may swab the cloaca to detect pathogens like avian influenza or West Nile virus.

Observing the Cloaca: Tips for Birdwatchers and Researchers

For amateur birdwatchers, the cloaca is rarely visible unless the bird is defecating, courting, or nesting. However, understanding its location and function enhances observational skills and appreciation of avian behavior.

Tips for identifying cloacal activity:

- Watch for defecation patterns: Many birds defecate immediately after takeoff. The white uric acid component is a telltale sign of cloacal output.

- Observe courtship behaviors: During breeding season, birds may briefly touch vents during mating. Look for close alignment and shuddering movements between pairs.

- Note nest sanitation: Parent birds often remove fecal sacs from chicks. These sacs originate in the cloaca and are carried away to keep nests clean.

- Use binoculars or telephoto lenses: To observe cloacal regions without disturbing birds, especially during sensitive times like nesting.

Researchers studying avian physiology or disease transmission often use non-invasive cloacal swabs. These provide valuable data on gut microbiota, hormone levels, and pathogen presence without harming the animal.

Common Misconceptions About the Cloaca in Birds

Several myths persist about the cloaca, often stemming from comparisons with mammalian anatomy.

- Misconception 1: 'Birds pee like mammals.' Reality: Birds don’t produce liquid urine. Uric acid is excreted with feces via the cloaca.

- Misconception 2: 'The cloaca is dirty or unsanitary.' Reality: Despite handling waste and eggs, the cloaca has mechanisms to prevent cross-contamination.

- Misconception 3: 'All birds mate with a cloacal kiss.' Reality: While most do, waterfowl use intromittent organs for internal fertilization.

- Misconception 4: 'The cloaca is the same as an anus.' Reality: It’s more complex—it integrates digestive, urinary, and reproductive tracts.

How the Cloaca Impacts Avian Flight and Survival

The cloaca contributes indirectly to flight efficiency. By eliminating the need for multiple external orifices, birds achieve a smoother body contour and reduced weight. Additionally, rapid waste expulsion helps lighten the load before flight—many birds defecate right before taking off.

In migratory species, this efficiency is critical. A streamlined cloacal system supports prolonged fasting and endurance flying by minimizing unnecessary metabolic demands and fluid loss.

Comparative Biology: Cloaca in Birds vs. Other Animals

Understanding what is cloaca in birds becomes richer when compared to other vertebrates.

- Mammals: Most have separate openings for urine (urethra), feces (anus), and reproduction (vagina or penis). Only monotremes (platypus and echidna) retain a cloaca.

- Reptiles: Like birds, reptiles have a cloaca used for excretion and reproduction. Some lizards and snakes also use it for pheromone release.

- Amphibians: Frogs and salamanders use the cloaca similarly, though some species practice external fertilization.

- Fish: Many fish have a cloaca, especially cartilaginous species like sharks.

This comparison underscores that the cloaca is not a primitive trait, but rather a highly adapted system suited to specific ecological niches.

FAQs About the Cloaca in Birds

Do all birds have a cloaca?

Yes, every bird species has a cloaca. It is a universal feature of avian anatomy, essential for excretion, reproduction, and digestion.

Can you see a bird's cloaca?

Typically, the cloaca is not visible unless the bird is defecating, laying an egg, or mating. It appears as a small slit beneath the tail feathers.

How do birds avoid contaminating eggs with waste?

The cloaca undergoes structural changes during egg-laying. The oviduct extends into the proctodeum, ensuring the egg bypasses fecal matter. Muscular contractions also help isolate pathways.

Do male and female bird cloacas look different?

Externally, they are nearly identical. Internally, males have connections to the testes via the vas deferens, while females connect to the ovary and oviduct.

Is the cloaca involved in bird communication?

Not directly, but some birds secrete pheromones or chemical signals through cloacal glands. These may play roles in mate selection or territorial marking, though research is ongoing.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4