An osprey bird, also known as Pandion haliaetus, is a large fish-eating raptor found on every continent except Antarctica. Often referred to as the 'fish hawk,' the osprey is uniquely adapted to hunting live fish, making it one of the most specialized birds of prey in the world. This remarkable bird of prey has evolved distinctive physical and behavioral traits that set it apart from other raptors, such as reversible outer toes, closable nostrils for diving, and a dense layer of oily feathers to repel water. Understanding what is osprey bird behavior, migration patterns, nesting habits, and ecological role provides valuable insight into both avian biology and environmental health.

Physical Characteristics and Identification

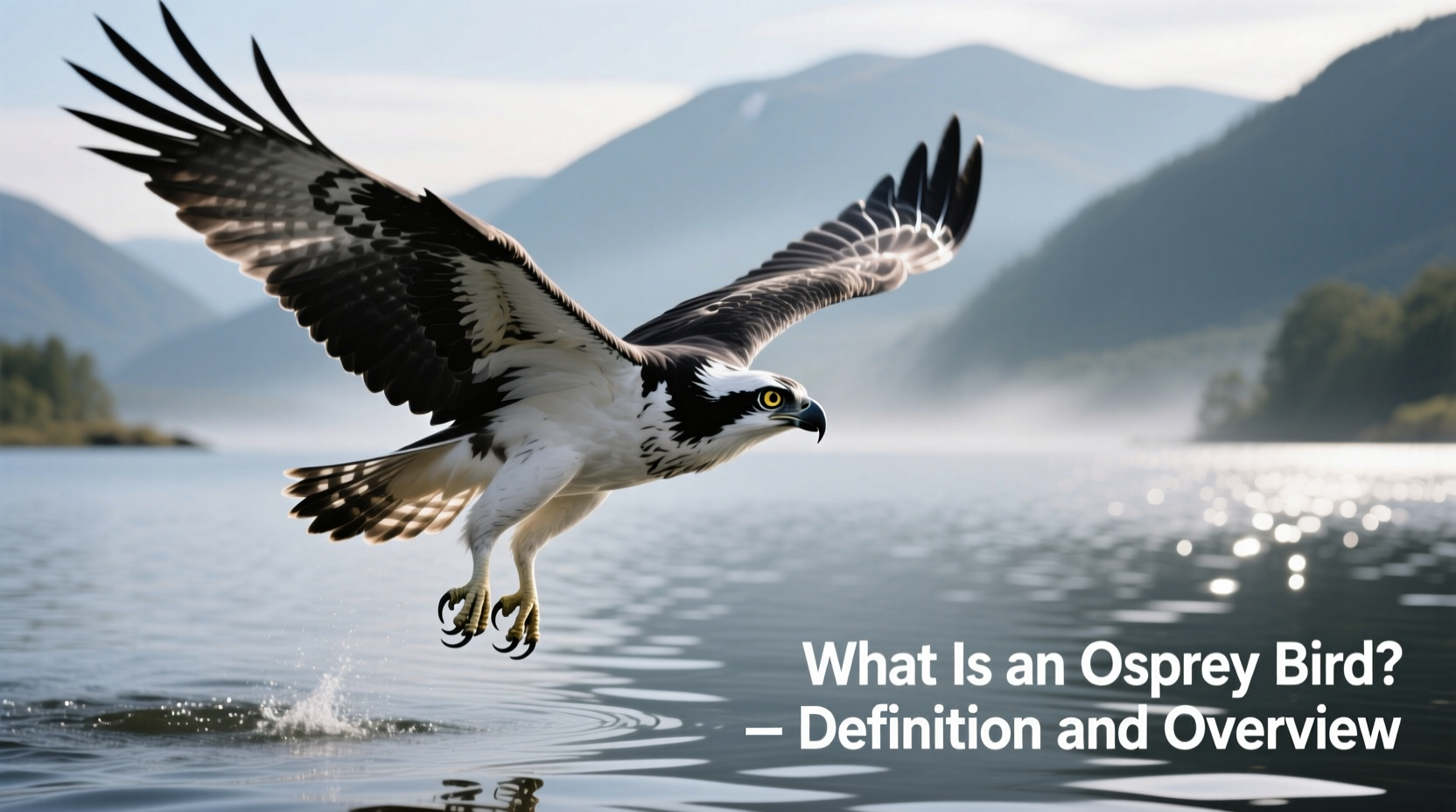

The osprey is a striking bird with a wingspan ranging from 59 to 70 inches (150–180 cm), making it slightly smaller than an eagle but larger than most hawks. Adults typically weigh between 3 to 4 pounds (1.4–2 kg). They have a distinctive appearance: dark brown upperparts, pure white underparts, and a prominent black eye stripe that runs across each side of the head. Their sharp, hooked beak and strong talons are perfectly designed for catching slippery fish.

One of the most notable features of the osprey is its reversible outer toe—a rare adaptation among birds. This allows the osprey to grasp fish with two toes in front and two behind, creating a secure grip. Additionally, their feet are covered in spiny footpads called spicules, which further enhance their ability to hold onto struggling prey. When in flight, ospreys often hold their wings in a distinct M-shape, especially when soaring over water bodies.

Habitat and Global Distribution

Ospreys are cosmopolitan in distribution, meaning they can be found on nearly every continent where suitable aquatic habitats exist. They inhabit coastal regions, lakes, rivers, reservoirs, and wetlands—anywhere fish are abundant. The species breeds in North America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, and parts of South America. During winter months, many northern populations migrate long distances to warmer climates. For example, ospreys breeding in Canada and the northern United States often fly to Central and South America for the non-breeding season.

This wide geographic range makes the osprey an excellent subject for international conservation efforts and citizen science projects like eBird and GCBO (Great Canadian Bird Observatory). Because they rely heavily on clean water ecosystems, osprey populations serve as bioindicators—scientists monitor their numbers and nesting success to assess environmental contamination and ecosystem health.

Diet and Hunting Behavior

Unlike most raptors that hunt small mammals, reptiles, or other birds, the osprey is almost exclusively piscivorous—its diet consists of more than 99% live fish. They typically target fish weighing between 6 to 12 ounces (170–340 grams), though they can catch larger prey up to 4 pounds. Common fish species include trout, mullet, bass, flounder, and perch, depending on regional availability.

Hunting usually occurs during daylight hours, particularly in the early morning and late afternoon. Ospreys soar at heights of 30 to 100 feet above the water, scanning for movement below. Once a fish is spotted, the bird hovers momentarily before plunging feet-first into the water with great precision. Their dive can submerge them entirely, and they use powerful wingbeats to lift themselves—and their catch—back into the air.

Their success rate in catching fish is surprisingly high, estimated at around 50% per attempt, far exceeding many other predatory birds. This efficiency stems from evolutionary adaptations such as nasal valves that prevent water intake, backward-facing scales on the talons, and oily plumage that sheds water quickly after a dive.

Nesting and Breeding Habits

Ospreys are monogamous and often mate for life. Pairs return to the same nesting site year after year, adding new material to the existing structure. Nests are large platforms made of sticks, lined with softer materials like seaweed, grass, or plastic debris (a growing concern due to pollution).

Nesting sites are typically located near water and placed in elevated positions—treetops, cliffs, utility poles, or man-made platforms specifically erected by conservation groups. In recent decades, artificial nesting platforms have played a crucial role in osprey recovery, especially in areas where natural nesting trees have been lost.

Females lay 2 to 4 eggs per clutch, which are incubated for about 35 to 42 days. Both parents share incubation duties, though the female spends more time on the nest. Chicks fledge at approximately 8 weeks old but remain dependent on their parents for several weeks afterward while learning to hunt.

Migratory Patterns and Seasonal Movements

Many osprey populations are highly migratory. Birds breeding in temperate zones must travel thousands of miles to reach tropical or subtropical wintering grounds. Satellite tracking studies have revealed incredible journeys—some individuals fly over 10,000 miles round-trip annually.

For instance, ospreys from New England may migrate through the eastern U.S., cross the Caribbean Sea, and winter in Venezuela or Brazil. European ospreys often travel down the West African coast. These migrations are timed with seasonal changes in food availability and weather conditions.

Migrants typically begin their southward journey in late summer or early fall (August to October), returning north in spring (March to May). Juvenile birds make their first migration alone, without parental guidance, relying on innate navigation abilities likely tied to Earth's magnetic field, celestial cues, and landscape features.

Conservation Status and Environmental Impact

The osprey was once severely threatened by the widespread use of DDT and other pesticides in the mid-20th century. These chemicals caused eggshell thinning, leading to reproductive failure and population declines. By the 1970s, osprey numbers had plummeted across North America and Europe.

Following the ban of DDT and implementation of conservation measures—including nest protection, pollution control, and public education—the species has made a remarkable recovery. Today, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the osprey as Least Concern globally, though local populations may still face threats from habitat loss, power line electrocution, and climate change.

Because ospreys sit atop the aquatic food chain, they accumulate toxins such as mercury and PCBs, making them important sentinels for monitoring water quality. Scientists regularly analyze blood and feather samples to track contaminant levels in various regions.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Beyond its biological importance, the osprey holds symbolic value in many cultures. In Native American traditions, the osprey is seen as a symbol of determination, vision, and spiritual clarity. Its ability to dive beneath the surface represents insight into hidden truths.

In Celtic mythology, the osprey was associated with wisdom and protection. Some maritime communities historically viewed osprey sightings as omens of good fishing or favorable winds. In modern times, the bird has become a mascot for environmental awareness and resilience, frequently featured in nature documentaries and wildlife rehabilitation campaigns.

Sports teams, including Major League Baseball’s Baltimore Orioles (whose name references another bird but shares regional association), and outdoor brands often use osprey imagery to convey strength, focus, and connection to nature.

How to Observe Ospreys: Tips for Birdwatchers

Observing ospreys in the wild can be a rewarding experience for amateur and experienced birders alike. Here are practical tips to increase your chances of spotting one:

- Visit coastal estuaries, lakeshores, or riverbanks—especially during spring and fall migration periods.

- Look for large stick nests on poles or dead trees near water; these are often reused year after year.

- Use binoculars or a spotting scope to observe feeding behavior without disturbing the birds.

- Listen for their high-pitched whistling calls, especially during courtship or when defending territory.

- Join local birding groups or attend guided wetland tours to learn from experts and contribute to citizen science databases.

Photographers should maintain a respectful distance and avoid using flash near nests. Disturbing nesting ospreys is illegal under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in the United States and similar laws in other countries.

Common Misconceptions About Ospreys

Despite growing awareness, several myths persist about ospreys:

- Myth: Ospreys are eagles.

Fact: While they resemble eagles in size and flight pattern, ospreys belong to their own taxonomic family, Pandionidae, separate from Accipitridae (which includes hawks, eagles, and kites). - Myth: Ospreys eat birds or mammals.

Fact: Over 99% of their diet is live fish; they rarely consume other prey unless fish are unavailable. - Myth: All ospreys migrate.

Fact: Populations in tropical and subtropical regions, such as Florida or the Caribbean, may be resident year-round if food is plentiful.

Osprey vs. Other Raptors: Key Differences

| Feature | Osprey | Bald Eagle | Red-Tailed Hawk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | Almost entirely fish | Fish, carrion, small animals | Rodents, rabbits, snakes |

| Wing Shape in Flight | M-shaped dihedral | Flat or slightly raised | Broad with splayed fingers |

| Foot Adaptations | Reversible outer toe, spicules | Strong talons, no reversibility | Standard raptor feet |

| Nesting Location | Near water, often on platforms | Near water, large trees or cliffs | Woodlands, urban areas |

| Vocalization | High-pitched whistle | Weak chirps, not eagle-like screams | Distinctive descending scream |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What is the difference between an osprey and an eagle?

- While both are large raptors, ospreys are specialized fish hunters with reversible toes and oily feathers, whereas eagles have broader diets and lack these specific adaptations. Ospreys also have a more pronounced M-shaped wing profile in flight.

- Do ospreys attack humans?

- No, ospreys do not attack humans. They are generally shy and avoid human contact. However, they may become defensive if approached too closely at a nest site, especially during breeding season.

- How long do osprey birds live?

- In the wild, ospreys typically live 15 to 20 years, though some individuals have lived over 25 years. Longevity depends on food availability, predation risks, and exposure to pollutants.

- Can ospreys swim?

- Ospreys don’t truly swim, but they can paddle with their wings to reach shore after a deep dive. Their buoyant feathers help keep them afloat temporarily.

- Why are ospreys coming back to my area?

- Increased osprey sightings often indicate improving water quality and fish populations. The installation of nesting platforms and reduced pesticide use have also contributed to their comeback in many regions.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4