Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, is a highly contagious viral infection that primarily affects birds, including wild species and domestic poultry. The most common strains responsible for recent outbreaks are H5N1 and H7N9, which have raised global concern due to their potential to spread from birds to humans. Understanding what is the bird flu involves recognizing its biological origins, transmission patterns, impact on wildlife and agriculture, and public health implications. This article explores the science behind avian influenza, its historical context, symptoms in birds and people, prevention strategies, and practical advice for birdwatchers and poultry keepers.

What Causes Bird Flu?

The causative agents of bird flu are influenza A viruses, which naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds such as ducks, geese, swans, and shorebirds. These birds often carry the virus without showing symptoms, acting as reservoirs. However, when the virus spreads to domesticated birds like chickens, turkeys, and quails, it can cause severe illness and high mortality rates—especially in cases of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI).

Influenza A viruses are classified based on two surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, leading to various combinations such as H5N1, H7N9, and H9N2. Among these, H5N1 has been particularly concerning since its emergence in Asia in the late 1990s due to its ability to infect multiple species, including mammals and humans.

History and Global Spread of Avian Influenza

The first recorded outbreak of avian influenza dates back to 1878 in Italy, though it wasn't until the 1950s that scientists identified the causative virus. The modern era of bird flu awareness began in 1996 with the identification of the H5N1 strain in geese in China. Since then, this strain has undergone significant evolution and spread across continents through migratory bird routes.

Major global outbreaks occurred in 2003–2006, affecting over 50 countries in Asia, Europe, and Africa. More recently, starting in 2020 and intensifying through 2022–2024, an unprecedented wave of HPAI H5N1 swept across North America, Europe, and parts of South America. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), tens of millions of commercial and backyard birds were culled to prevent further spread.

This ongoing circulation highlights the importance of international surveillance and rapid response systems. Migratory birds play a key role in long-distance transmission, especially during seasonal movements between breeding and wintering grounds.

Symptoms of Bird Flu in Birds

Clinical signs vary depending on the virus strain and host species. Low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) may cause mild respiratory issues, decreased egg production, or ruffled feathers. In contrast, HPAI strains like H5N1 can lead to sudden death with little warning.

Common symptoms in infected birds include:

- Sudden death without prior signs

- Swelling of the head, eyelids, comb, wattles, and legs

- Purple discoloration of wattles, combs, and legs

- Respiratory distress (coughing, sneezing, nasal discharge)

- Decreased food and water intake

- Reduced egg production or soft-shelled/abnormal eggs

- Neurological signs such as tremors, lack of coordination, or twisting of the neck

Wild birds, particularly waterfowl and raptors, may show neurological impairment or die en masse. Observations of sick or dead birds should be reported to local wildlife authorities or veterinary services.

Can Humans Get Bird Flu?

Yes, although human infections are rare, they do occur—primarily among individuals with close contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. Most cases have involved people working in live bird markets, poultry farms, or those handling sick/dead birds without protective gear.

Human symptoms range from mild flu-like illness (fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches) to severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Case fatality rates for H5N1 in humans have historically been high—over 50% in some regions—but the total number of confirmed cases remains low globally.

There is currently no sustained human-to-human transmission of bird flu, which limits pandemic risk. However, scientists monitor the virus closely because genetic reassortment (mixing of viral genes) could potentially create a strain capable of efficient human spread—a major public health concern.

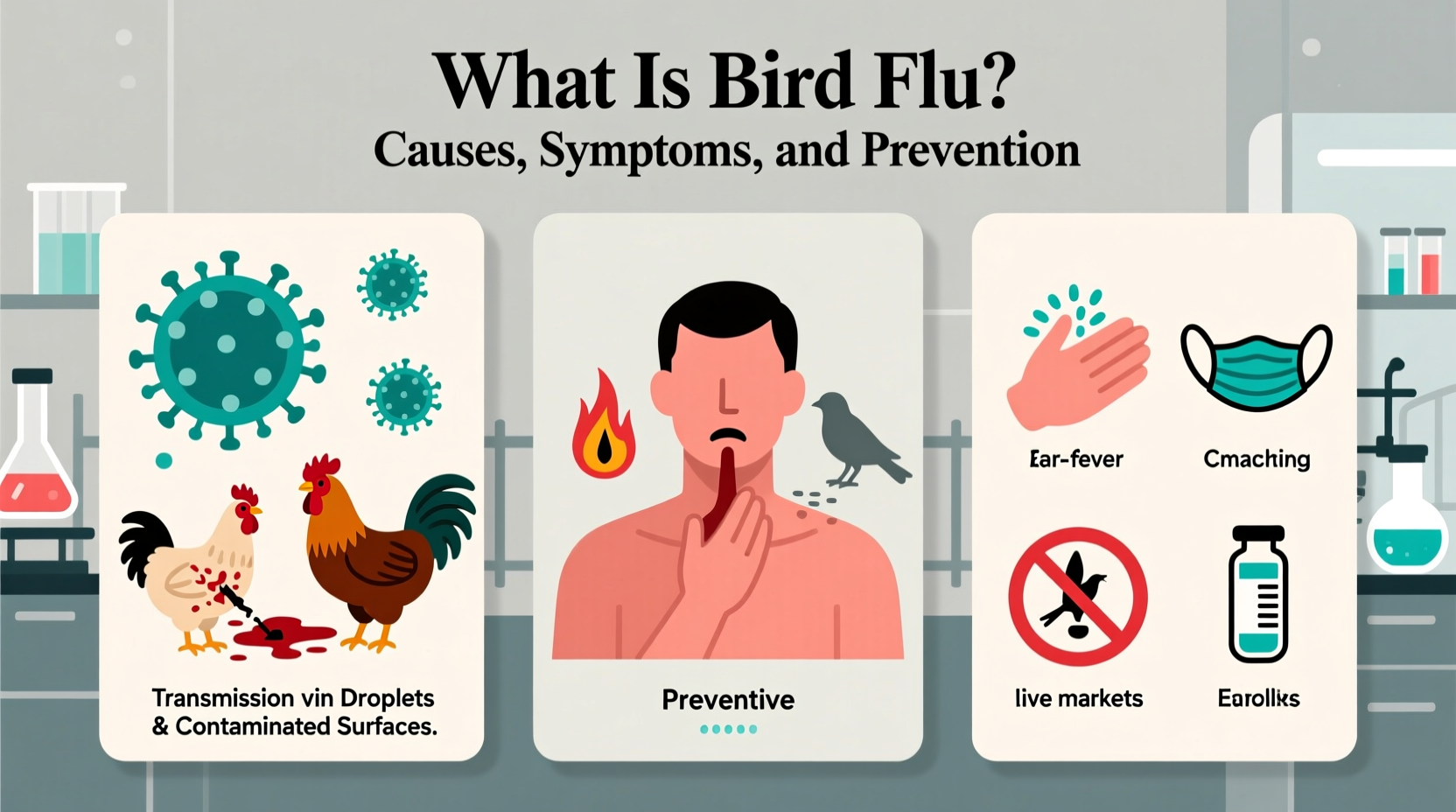

Transmission Pathways and Risk Factors

Bird flu spreads through direct contact with infected birds or indirect exposure to contaminated surfaces, feces, saliva, or respiratory secretions. The virus can survive in cool, moist environments for extended periods, making biosecurity critical.

Key transmission routes include:

- Contact with infected wild or domestic birds

- Contaminated equipment, clothing, footwear, or vehicles

- Airborne particles in enclosed spaces (e.g., barns)

- Water sources shared by wild and domestic birds

Risk factors for spillover into humans include:

- Handling sick or dead birds

- Visiting live bird markets

- Consuming undercooked poultry products (though properly cooked meat poses no risk)

- Lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) in high-risk settings

To reduce risk, avoid touching wild birds, especially if found dead or ill. Report sightings to local agencies such as state wildlife departments or national hotlines.

Impact on Wildlife and Ecosystems

The current H5N1 strain has had devastating effects on wild bird populations worldwide. Seabird colonies, including puffins, gannets, and albatrosses, have experienced mass die-offs. Raptors such as eagles and owls are also vulnerable, likely due to scavenging infected carcasses.

In North America, the USDA and U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have documented widespread mortality in over 100 species. Some conservationists fear long-term ecological disruptions, particularly in island ecosystems where seabirds play vital roles in nutrient cycling.

Monitoring programs use laboratory testing of dead birds and environmental sampling to track virus distribution. Citizen scientists and birdwatchers contribute valuable data through platforms like eBird and iNaturalist, helping detect early signs of outbreaks.

| Bird Species | Susceptibility to H5N1 | Observed Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Ducks and Geese | Moderate to High | Carriers; may show mild to severe symptoms |

| Chickens and Turkeys | Very High | High mortality; rapid spread in flocks |

| Seabirds (e.g., Gannets) | Extremely High | Mass mortality events observed |

| Raptors (e.g., Eagles) | High | Fatal infections linked to scavenging |

| Passerines (songbirds) | Low to Moderate | Limited reports; less commonly affected |

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures

Preventing bird flu requires coordinated efforts at individual, farm, and governmental levels. For backyard poultry owners and small-scale farmers, implementing strict biosecurity practices is essential:

- Isolate domestic birds from wild birds

- Use dedicated clothing and footwear when handling birds

- Disinfect cages, feeders, and waterers regularly

- Avoid visiting other poultry farms or bird markets unnecessarily

- Report any unusual bird deaths immediately

Commercial operations must follow enhanced protocols, including surveillance, quarantine zones, and controlled transport. Vaccination is used in some countries but is not universally adopted due to challenges in distinguishing vaccinated from infected birds (DIVA principle).

For wild bird enthusiasts, maintaining distance from wildlife and avoiding feeding birds in areas with known outbreaks helps minimize risks. Binoculars and spotting scopes allow safe observation while supporting conservation monitoring.

Current Outbreak Status and Regional Variations (2024)

As of 2024, avian influenza remains active in many regions. The United States continues to report sporadic outbreaks in commercial and backyard flocks, particularly in the Midwest and Western states. Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, and parts of West Africa also face ongoing challenges.

Regional differences stem from climate, bird migration patterns, farming density, and surveillance capacity. Cold climates prolong virus survival, increasing transmission risk during winter months. Countries with dense poultry industries may experience faster spread unless stringent controls are enforced.

Public health agencies recommend checking official sources such as the CDC (U.S.), DEFRA (UK), or FAO (global) for real-time updates. Local agricultural extensions often provide region-specific guidance for farmers and bird owners.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Misconception: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Properly cooked poultry and eggs are safe. Heat destroys the virus. - Misconception: All sick birds have bird flu.

Fact: Many diseases mimic bird flu symptoms. Lab testing is required for confirmation. - Misconception: Pet birds are at high risk from casual outdoor exposure.

Fact: Indoor pet birds face minimal risk unless exposed to infected wild birds or contaminated materials. - Misconception: There’s a human pandemic imminent.

Fact: No evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission exists as of 2024.

Practical Tips for Birdwatchers and Nature Enthusiasts

If you enjoy observing birds in nature, consider the following precautions during active bird flu periods:

- Do not touch sick or dead birds.

- Wash hands thoroughly after outdoor activities near wetlands or bird habitats.

- Disinfect binoculars, cameras, and gear after visits to high-risk areas.

- Participate in citizen science projects that help track disease spread.

- Follow local advisories regarding park closures or restrictions on bird feeding.

Supporting habitat protection and clean water initiatives indirectly reduces stress on bird populations, improving their resilience to diseases like avian influenza.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Can dogs or cats get bird flu?

Yes, though rare. Cats can become infected by eating infected birds. Dogs are less susceptible but should avoid contact with dead wildlife.

Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

A pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine exists in limited supply for emergency use, but it is not available to the general public. Seasonal flu vaccines do not protect against bird flu.

How long does the bird flu virus survive in the environment?

It can last several days in water or moist soil, up to weeks in cold conditions. Sunlight and drying reduce viability.

Should I stop feeding backyard birds?

If your area has confirmed outbreaks, experts recommend pausing bird feeding and cleaning feeders weekly with a 10% bleach solution.

Where can I report a dead wild bird?

Contact your state wildlife agency, local veterinarian, or national hotline such as the USDA's toll-free number or equivalent in your country.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4