Bird flu in humans, also known as avian influenza, is a rare but serious viral infection that can be transmitted from infected birds to people. The most common strain responsible for human cases is the H5N1 virus, which has caused sporadic outbreaks since its emergence in 1997. While bird flu primarily affects poultry and wild birds, certain strains have demonstrated the ability to cross the species barrier and infect humans, typically through direct contact with infected birds or contaminated environments. Understanding what is the bird flu in humans involves recognizing both its biological mechanisms and public health implications, including symptoms, transmission risks, prevention strategies, and global surveillance efforts.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Evolution

The first documented case of human infection with the H5N1 strain occurred in Hong Kong in 1997, marking a pivotal moment in infectious disease research. Since then, various subtypes—including H7N9, H5N6, and H9N2—have emerged across Asia, Europe, and Africa. These viruses belong to the influenza A family, characterized by surface proteins hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). There are 18 known H subtypes and 11 N subtypes, but only a few have shown the capacity to infect humans.

Wild aquatic birds, particularly ducks and geese, serve as natural reservoirs for avian influenza viruses. They often carry the virus without showing symptoms, shedding it through feces, saliva, and nasal secretions. When these pathogens spread to domestic poultry farms, they can mutate into highly pathogenic forms, leading to mass bird deaths and increased risk of zoonotic transmission—the process by which diseases jump from animals to humans.

How Does Bird Flu Spread to Humans?

Transmission of bird flu to humans typically occurs through close contact with infected live or dead birds, especially in backyard flocks or live bird markets. People working in poultry farming, veterinary services, or wildlife handling are at higher occupational risk. Contaminated surfaces, such as cages, feed, or water sources, can also harbor the virus. However, there is currently no sustained human-to-human transmission of H5N1 or other major avian strains, which limits large-scale outbreaks.

It's important to clarify a common misconception: eating properly cooked poultry or eggs does not transmit bird flu. The virus is destroyed at temperatures above 70°C (158°F), so thorough cooking eliminates any potential risk. Nevertheless, cross-contamination during food preparation remains a concern if utensils or surfaces come into contact with raw infected meat.

Symptoms and Health Risks in Humans

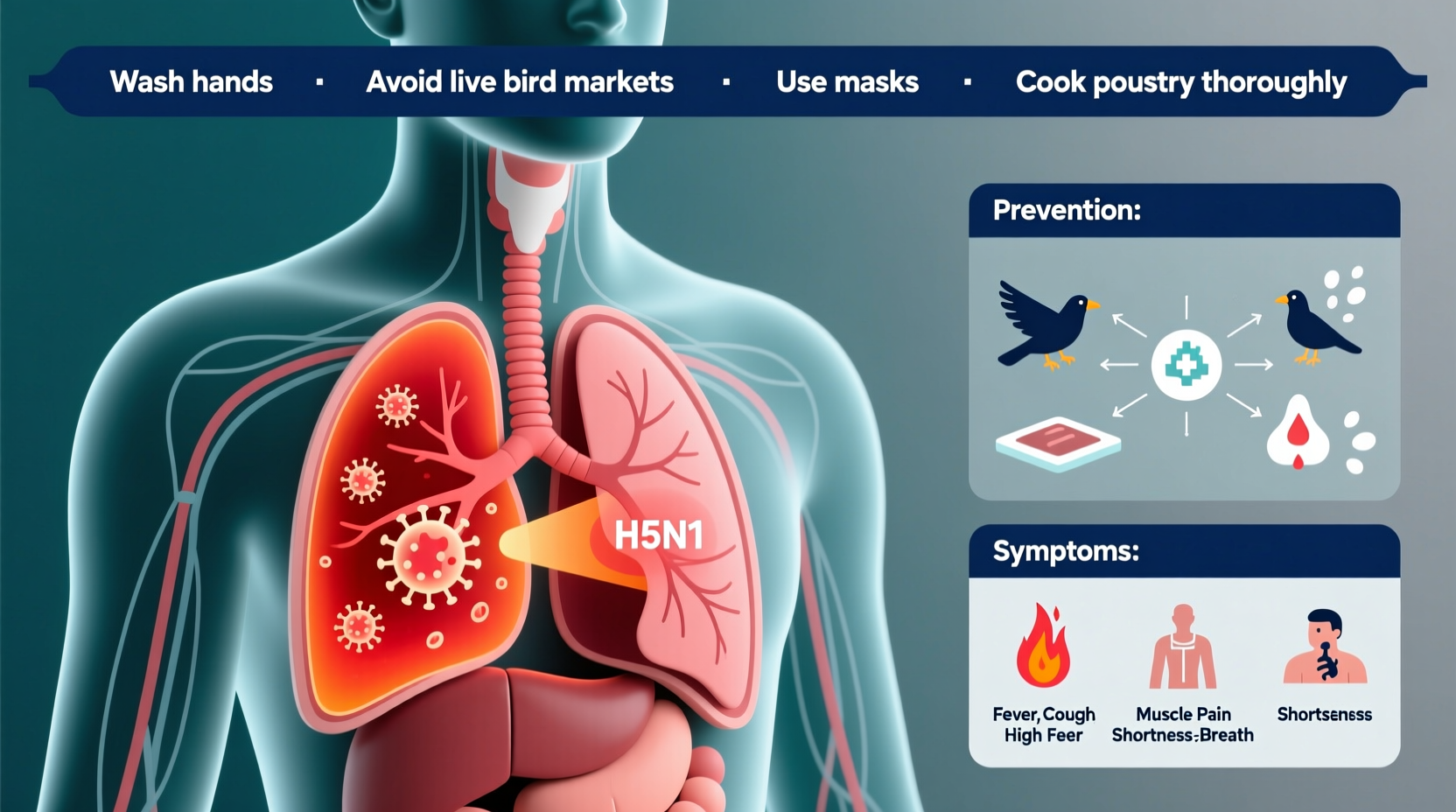

In humans, bird flu symptoms can range from mild respiratory illness to severe pneumonia and multi-organ failure. Early signs resemble seasonal flu—fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches—but may rapidly progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), especially with H5N1 infections. Case fatality rates vary by strain; H5N1 has historically had a mortality rate exceeding 50% in confirmed cases, though this figure may be skewed due to underreporting of milder infections.

Children and individuals with weakened immune systems appear more vulnerable to complications. Because the virus targets deep lung tissues rather than upper airways, standard flu treatments like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) may be less effective unless administered early. Rapid diagnostic testing and immediate antiviral therapy are critical for improving outcomes.

Global Surveillance and Outbreak Response

Given the pandemic potential of avian influenza, international organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintain robust monitoring systems. These agencies track outbreaks in birds and humans, share genetic sequence data, and support vaccine development. For instance, the CDC’s Influenza Division operates the Global Virome Project to detect emerging strains before they gain human transmissibility.

Recent years have seen an increase in H5N1 detections among wild birds and commercial poultry across North America, Europe, and Africa. In 2022, the United States experienced one of its largest-ever avian flu outbreaks, affecting over 58 million birds. This led to temporary restrictions on poultry movement and heightened biosecurity measures. Public health officials closely monitor such events for signs of adaptive mutations that could enable efficient human-to-human spread.

Prevention Strategies for At-Risk Populations

For those living in or traveling to regions with active bird flu outbreaks, several precautions reduce exposure risk:

- Avoid visiting live bird markets or poultry farms.

- Wear protective gear (masks, gloves) when handling birds or cleaning coops.

- Practice frequent handwashing with soap and water after outdoor activities in rural areas.

- Report sick or dead birds to local authorities instead of handling them directly.

Vaccination plays a dual role: protecting poultry flocks and preparing for potential human pandemics. While routine vaccination of humans against bird flu is not currently recommended, candidate vaccines for H5N1 and H7N9 are stockpiled by some governments as part of pandemic preparedness plans. Seasonal flu shots do not protect against avian strains but are still advised to reduce overall influenza burden on healthcare systems.

Differences Between Bird Flu and Seasonal Influenza

Although both are caused by influenza A viruses, bird flu and seasonal flu differ significantly in origin, transmission, and impact. Seasonal flu circulates annually among humans, spreads easily via respiratory droplets, and affects millions worldwide each year. In contrast, bird flu originates in birds, rarely infects humans, and lacks sustained person-to-person transmission.

Another key distinction lies in immunity. Most adults have partial immunity to seasonal flu due to prior infections or vaccinations. However, because avian influenza strains are antigenically distinct, humans generally lack pre-existing immunity, making them potentially more dangerous if they acquire the ability to spread efficiently between people.

| Feature | Bird Flu (e.g., H5N1) | Seasonal Flu |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Birds (zoonotic) | Human circulation |

| Transmission to Humans | Rare, requires direct contact | Easily spreads person-to-person |

| Mortality Rate | High (~50% for H5N1) | Low (<0.1%) |

| Vaccine Availability | Limited stockpiles | Annual vaccines available |

| Pandemic Risk | High if mutation occurs | Low (predictable patterns) |

Current Status and Ongoing Research

As of 2024, no widespread human epidemic of bird flu has occurred, but isolated cases continue to emerge, particularly in countries with dense poultry populations and limited veterinary oversight. Scientists are actively studying how avian viruses adapt to mammalian hosts by analyzing genetic changes in circulating strains. One area of focus is the PB2-E627K mutation, which allows the virus to replicate more efficiently at human body temperature (37°C vs. bird body temperature of ~41°C).

Researchers are also exploring universal influenza vaccines that target conserved regions of the virus, potentially offering protection across multiple strains—including avian variants. Such advancements could revolutionize pandemic preparedness and reduce reliance on strain-specific formulations.

Travel Advisories and Regional Considerations

Travelers should consult national health advisories before visiting regions experiencing avian flu outbreaks. The CDC and WHO issue travel notices recommending avoidance of high-risk areas, such as affected farms or wet markets. Some countries implement temporary import bans on poultry products from outbreak zones, impacting trade and consumer availability.

Regional differences in reporting accuracy and healthcare access influence case detection. High-income nations tend to have better surveillance and diagnostic capabilities, while low-resource settings may miss mild cases or lack laboratory confirmation. This variability underscores the need for global cooperation in disease tracking and response coordination.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza. One is that all bird species pose equal risk—however, songbirds and raptors are far less likely to carry or transmit H5N1 compared to waterfowl and gallinaceous birds like chickens and turkeys. Another myth is that bird flu is airborne like measles; in reality, transmission requires close proximity to infected material, not casual airborne exposure.

Additionally, some believe that pet birds are a major source of infection. While possible, household pets like parrots or canaries are unlikely to contract or spread the virus unless exposed to infected wild birds or uncooked poultry.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Can bird flu spread from person to person?

No sustained human-to-human transmission has been documented. Rare instances involve very close, prolonged contact, but the virus does not spread easily between people. - Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

Candidate vaccines exist for H5N1 and H7N9 and are held in emergency stockpiles, but they are not commercially available for general use. - What should I do if I find a dead bird?

Do not touch it. Contact local wildlife or public health authorities who can safely collect and test the specimen. - Are migratory birds responsible for spreading bird flu?

Yes, wild migratory waterfowl play a key role in dispersing the virus across continents, especially along flyways used during seasonal migrations. - How long can the bird flu virus survive in the environment?

The virus can remain infectious for days in cool, moist conditions—up to two weeks in water and several days on surfaces like soil or feces.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4