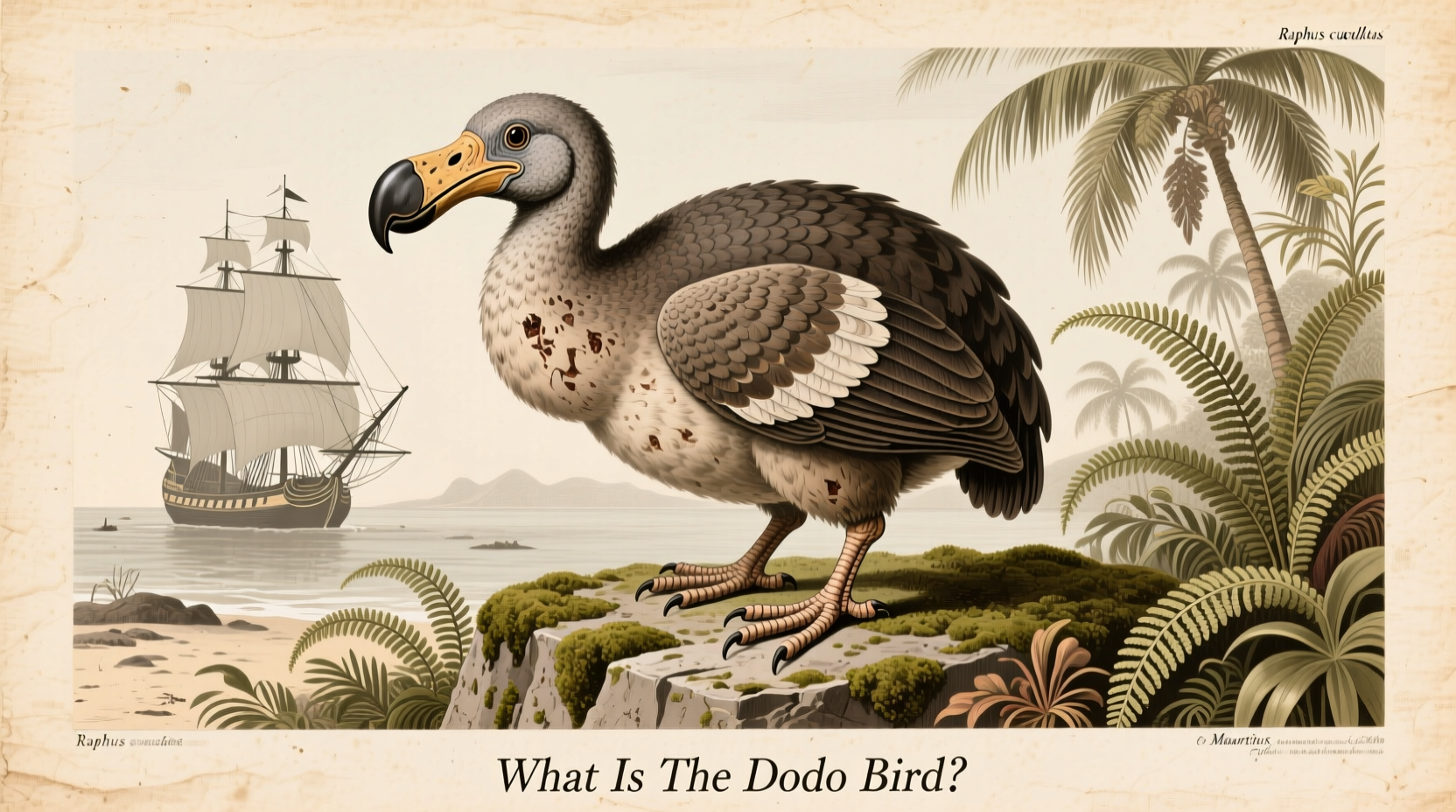

The dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) was a flightless bird endemic to the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, now famously extinct and often cited in discussions about human-driven extinction events. What is the dodo bird if not one of the most iconic symbols of ecological loss in modern history? This large, plump bird, unable to fly due to evolutionary adaptations on an isolated island with no natural predators, fell victim to human colonization, invasive species, and habitat destruction in the late 17th century. Understanding what the dodo bird was—and why it disappeared—offers critical insights into conservation biology, island ecosystems, and the long-term consequences of human activity on vulnerable species.

Historical Discovery and Early Encounters

The dodo bird was first encountered by humans in the early 1598 when Dutch sailors landed on the island of Mauritius during exploratory voyages to the East Indies. At the time, the island was uninhabited and teemed with unique wildlife that had evolved in isolation for millions of years. The dodo, having no fear of humans due to the absence of predators, was easily captured and killed. Early accounts from sailors describe the bird as clumsy, fat, and unpalatable, though it was still hunted for food. These initial encounters marked the beginning of the end for the species.

By the mid-1600s, just over 60 years after its discovery, the dodo was effectively extinct in the wild. The last widely accepted sighting of a live dodo was recorded around 1662, although some evidence suggests individuals may have survived into the 1680s. Unlike many extinct animals known only through fossils, the dodo is documented through written descriptions, drawings, and even a few preserved remains—including a skull and partial skeleton held at Oxford University and a nearly complete skeleton found in a cave in the 19th century.

Biological Characteristics of the Dodo

Scientifically classified as Raphus cucullatus, the dodo belonged to the family Columbidae, making it a close relative of modern pigeons and doves. Despite its bulky appearance, genetic studies conducted in the 2000s confirmed that the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) is its closest living relative. This evolutionary link highlights how island isolation can lead to dramatic morphological changes over relatively short geological timescales.

Adult dodos stood about three feet (90 cm) tall and weighed between 20 to 30 pounds (9–14 kg), with stout legs, small wings unsuitable for flight, and a large, hooked beak. Its feathers were grayish, and it possessed a distinctive tufted tail. Due to the lack of predation pressure, the dodo evolved to become flightless—a common trait among island birds such as the kiwi, kakapo, and moa. It fed primarily on fruits, seeds, nuts, and possibly roots, playing a vital ecological role as a seed disperser in Mauritius’s forests.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Raphus cucullatus |

| Family | Columbidae (pigeons and doves) |

| Height | Approximately 90 cm (3 ft) |

| Weight | 9–14 kg (20–30 lbs) |

| Diet | Fruits, seeds, nuts, roots |

| Flight Capability | None – fully flightless |

| Extinction Date | Mid-to-late 17th century (~1662–1680s) |

| Habitat | Tropical forests of Mauritius |

Causes of Extinction

The extinction of the dodo bird was not caused by a single factor but rather a cascade of interrelated threats introduced by human activity. While hunting contributed to population decline, it was not the primary driver of extinction. More devastating were the invasive species brought to Mauritius by settlers—such as rats, pigs, dogs, and crab-eating macaques—that preyed on dodo eggs and competed for food resources. These animals thrived in the new environment, rapidly multiplying and disrupting the fragile island ecosystem.

In addition, deforestation for agriculture and settlement destroyed much of the dodo’s natural habitat. With limited range and low reproductive rates—likely laying only one egg per clutch—the species could not adapt quickly enough to these sudden environmental changes. The combination of predation on eggs and juveniles, habitat loss, and direct human exploitation sealed the fate of the dodo within less than a century of contact with Europeans.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Although the dodo vanished centuries ago, its cultural legacy endures. The phrase “dead as a dodo” has entered common usage to signify something obsolete or completely extinct. In literature, the dodo gained renewed fame through Lewis Carroll’s *Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland* (1865), where a comical, self-important dodo appears in the Caucus Race. While Carroll’s portrayal added whimsy, it also cemented the bird’s image in popular imagination as odd, clumsy, and slightly foolish—misconceptions that obscure its true ecological importance.

In contemporary discourse, the dodo serves as a powerful symbol of human-caused extinction and environmental negligence. It is frequently used in educational materials, conservation campaigns, and scientific discussions about biodiversity loss. As climate change and habitat destruction accelerate global extinction rates, the story of the dodo remains a cautionary tale: even seemingly abundant species can disappear rapidly when faced with unchecked anthropogenic pressures.

Modern Scientific Research and Rediscovery Efforts

In recent decades, advances in paleontology, genetics, and digital reconstruction have allowed scientists to learn more about the dodo than ever before. CT scans of existing skulls and bones have enabled researchers to create accurate 3D models of the bird’s anatomy, revealing details about its brain size, sensory capabilities, and posture. Studies suggest the dodo had a well-developed sense of smell—unusual among birds—which may have helped it locate fruit in dense forests.

Genetic analysis using DNA extracted from museum specimens has clarified the dodo’s evolutionary lineage, confirming its placement within the pigeon family tree. These findings challenge outdated notions of the dodo as a poorly adapted evolutionary failure. Instead, modern science portrays it as a highly specialized species perfectly suited to its niche—until that niche was abruptly destroyed.

There have been speculative discussions about de-extinction technologies potentially bringing back the dodo using CRISPR gene-editing techniques and stem cell manipulation. However, such efforts remain theoretical and face significant ethical, logistical, and ecological hurdles. Even if technically feasible, reintroducing a resurrected dodo would require a restored and protected habitat—an outcome that currently does not exist on Mauritius.

Ecological Lessons from the Dodo’s Extinction

The extinction of the dodo offers several enduring lessons for conservation biology and environmental policy:

- Island ecosystems are especially vulnerable. Species that evolve in isolation without predators often lack defensive behaviors or physical adaptations to survive introduced threats.

- Secondary impacts matter. Even moderate levels of hunting can become catastrophic when combined with invasive species and habitat fragmentation.

- Extinction is irreversible. Once lost, a species cannot be recovered through conventional means, underscoring the importance of proactive protection.

- Public awareness drives action. The dodo’s symbolic status helps raise awareness about current extinction crises affecting species like the vaquita, northern white rhino, and numerous amphibians.

How the Dodo Compares to Other Extinct Flightless Birds

The dodo was not unique in its evolutionary path. Many islands hosted flightless birds that evolved similarly due to predator-free environments. Examples include:

- Moa (New Zealand): Giant flightless birds, some reaching over 12 feet tall; hunted to extinction by Māori settlers by the 15th century.

- Kakapo (New Zealand): A critically endangered nocturnal parrot, still alive today thanks to intensive conservation efforts.

- Great Auk (North Atlantic): A flightless seabird hunted extensively for its feathers and oil; last confirmed sighting in 1844.

- Elephant Bird (Madagascar): One of the largest birds ever, standing up to 10 feet tall; went extinct around 1000 CE, likely due to human activity.

These cases reinforce the pattern: human arrival on ecologically naïve islands often leads to rapid faunal collapse unless protective measures are implemented immediately.

Where to Learn More About the Dodo Today

While no living dodos exist, several museums house original remains and reconstructions:

- Oxford University Museum of Natural History: Holds the only known soft tissue remains (a head and foot).

- Natural History Museum, London: Features skeletal mounts and historical illustrations.

- Mauritius Institute: Displays local fossils and educational exhibits on native species.

- Interactive Exhibits: Institutions like the Smithsonian and the American Museum of Natural History include the dodo in broader evolution and extinction exhibits.

For those interested in deeper study, peer-reviewed journals such as *Nature*, *Science*, and *Journal of Zoology* regularly publish research on dodo biology, paleoecology, and conservation implications.

Common Misconceptions About the Dodo

Several myths persist about the dodo bird:

- Myth: The dodo was stupid or poorly evolved.

Truth: It was well-adapted to its environment; its traits were maladaptive only after human disruption. - Myth: It was hunted to extinction directly.

Truth: Hunting played a role, but invasive species and habitat loss were far more significant. - Myth: The dodo was slow and clumsy.

Truth: Recent biomechanical studies suggest it was likely quite agile in forest terrain. - Myth: We have complete skeletons of many individuals.

Truth: Only a handful of partial remains exist; most knowledge comes from subfossils and historical records.

Frequently Asked Questions

- When did the dodo bird go extinct?

- The dodo bird is believed to have gone extinct by the late 17th century, with the last confirmed sighting around 1662. Some evidence suggests isolated populations may have survived until the 1680s.

- Why couldn't the dodo fly?

- The dodo evolved on an island with no natural predators and abundant food, so flight became unnecessary. Over generations, its wings reduced in size while its body grew larger—a common evolutionary trend in island birds.

- Is the dodo related to dinosaurs?

- No, the dodo is not a dinosaur, but all birds are considered modern descendants of theropod dinosaurs. The dodo itself was a type of pigeon, evolving tens of millions of years after non-avian dinosaurs went extinct.

- Could we bring the dodo back?

- While theoretical de-extinction projects exist, no viable plan to resurrect the dodo is currently underway. Challenges include incomplete DNA, lack of suitable surrogate species, and absence of a safe, restored habitat.

- What does the word 'dodo' mean?

- The origin of the name 'dodo' is uncertain. It may derive from the Dutch word 'dodoor,' meaning 'sluggard,' or from 'dodaars,' a term for a type of puffin, possibly due to visual similarities in early sketches.

In summary, the question 'what is the dodo bird?' extends beyond mere biological classification. It invites reflection on humanity’s role in shaping—and sometimes ending—life on Earth. As both a scientific subject and a cultural icon, the dodo continues to educate, inspire, and warn future generations about the fragility of nature when left unprotected.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4