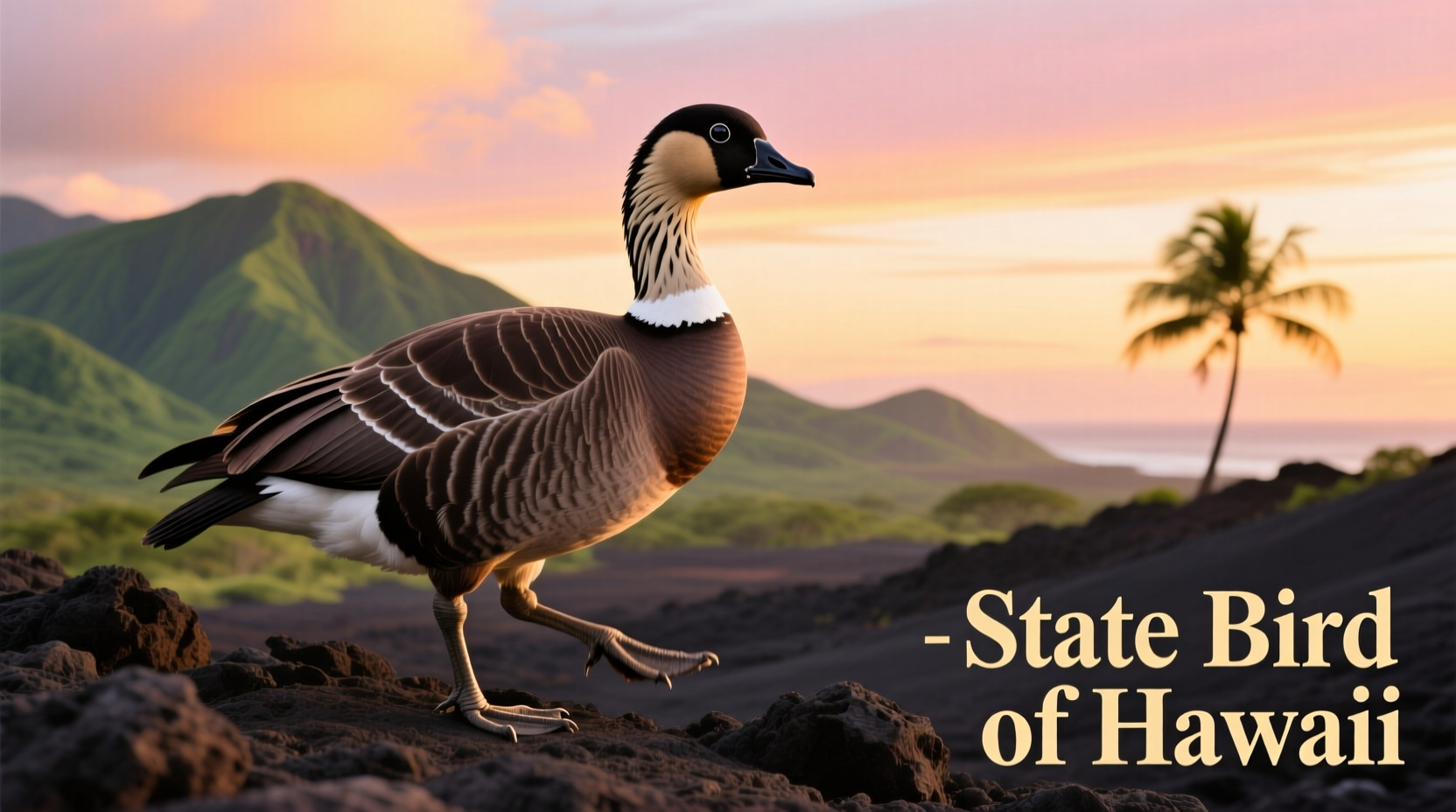

The state bird of Hawaii is the nene, also known as the Hawaiian goose (Branta sandvicensis). This unique waterfowl was officially designated as Hawaii’s state bird in 1957, making it a central symbol of the islands’ distinctive natural heritage. When searching for information on what is the state bird in Hawaii, many nature enthusiasts and students discover that the nene stands out not only for its cultural importance but also for its remarkable evolutionary journey from ancestral Canada geese to an endemic species adapted to volcanic landscapes. Unlike most geese, the nene spends much of its life on land, a trait shaped by centuries of isolation in the Hawaiian archipelago.

Historical Background: How the Nene Became Hawaii’s State Bird

The designation of the nene as the official state bird of Hawaii occurred on June 2, 1957, through legislative action that recognized both its rarity and symbolic value. At the time, the species was already facing severe population decline due to habitat loss, predation by introduced species such as mongooses and feral cats, and hunting pressures during earlier settlement periods. The move to name the nene the state bird was not merely ceremonial—it served as an early conservation signal, drawing public attention to the bird’s precarious status.

Prior to European contact, the nene was more widespread across several Hawaiian islands, including Maui, Kaua‘i, and O‘ahu. Fossil records indicate that the species evolved over 500,000 years ago from the Canada goose (Branta canadensis), which likely arrived in Hawaii via storm-driven migration. Over millennia, the nene adapted to island life: its webbing between toes reduced for better traction on lava fields, its neck markings became distinctively patterned, and its call evolved into a softer, more nasal tone compared to its continental relatives.

Biological Characteristics of the Nene

The nene is a medium-sized bird, measuring about 25 inches in length with a wingspan reaching up to 36 inches. Males typically weigh around 4.5 pounds, while females are slightly smaller. Its plumage features a mix of soft gray-brown feathers on the back, a black head and neck with elegant buff-colored stripes running down the sides of the cheeks and neck—markings that resemble a ruffled collar. These visual traits help distinguish it from other geese species.

One of the most notable adaptations of the nene is its partially webbed feet. While still capable of swimming, the reduced webbing allows it to walk efficiently across rugged terrain like hardened lava flows, grasslands, and shrublands—habitats common in its current range on Hawai‘i Island, Maui, and Moloka‘i. Another adaptation is its diet: primarily herbivorous, feeding on leaves, seeds, berries, and grasses, often foraging in open areas near native plants such as ‘ākala (Hawaiian raspberry) and pūkiawe.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Branta sandvicensis |

| Length | Approximately 25 inches |

| Wingspan | Up to 36 inches |

| Weight (Male) | Average 4.5 lbs |

| Habitat | Volcanic slopes, grasslands, shrublands |

| Diet | Leaves, seeds, berries, grasses |

| Conservation Status | Threatened (U.S. Federal List) |

Cultural and Symbolic Significance in Hawaiian Tradition

In Native Hawaiian culture, the nene holds spiritual and ecological significance. Known as nēnē in the Hawaiian language—a name derived from the bird’s distinctive call—the species appears in oral traditions and chants as a symbol of resilience and aloha ‘āina (love of the land). Some legends describe the nene as a kinolau, or physical manifestation, of Lono, the god associated with fertility, agriculture, rainfall, and peace.

Historically, high-ranking ali‘i (chiefs) were sometimes presented with nene as gifts, reflecting their esteemed status. However, strict kapu (taboos) once protected certain birds, including the nene, from overharvesting. With the breakdown of traditional governance systems after Western contact, these protections eroded, contributing to population declines.

Today, the nene serves as a living emblem of Hawaiian identity and environmental stewardship. It appears on educational materials, state tourism campaigns, and even local artwork, reinforcing its role not just as a biological entity but as a cultural touchstone.

Conservation Efforts and Recovery Progress

By the mid-20th century, the nene population had plummeted to fewer than 30 individuals in the wild, largely due to invasive predators, habitat destruction, and human activity. In response, intensive conservation programs began in the 1940s, led by figures such as Sir Peter Scott at Slimbridge Wildfowl Reserve in England, who pioneered captive breeding techniques. Eggs and live birds were transported overseas and bred successfully, with offspring later reintroduced into protected habitats in Hawaii.

Domestic efforts followed, involving agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW), and nonprofit organizations like the Pacific Rim Conservation. Strategies included predator control, habitat restoration, captive rearing, and public education. Fencing off critical nesting zones and installing motion-sensor cameras have helped monitor nests and deter mongoose incursions.

Thanks to decades of coordinated work, the wild population has rebounded to approximately 3,500 birds as of 2023, though the species remains listed as threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Continued threats include vehicle strikes (especially on roads cutting through Haleakalā National Park), climate change impacts on alpine ecosystems, and disease transmission from non-native birds.

Where to See the Nene in the Wild

For visitors and birdwatchers seeking to observe the state bird of Hawaii in its natural environment, several locations offer reliable sightings:

- Haleakalā National Park (Maui): The subalpine shrublands above 7,000 feet provide prime habitat. Early morning drives along the Haleakalā Highway often yield views of nene pairs grazing near park entrances or nesting on cinder cones.

- Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park (Big Island): Look for nene near Kīlauea Visitor Center, Devastation Trail, and along Crater Rim Drive. Rangers frequently report sightings during dawn patrols.

- Mauna Kea Access Road (Big Island): Despite elevation challenges, this area supports a growing population, particularly near the Onizuka Center for International Astronomy.

- James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge (O‘ahu): A successful reintroduction site where guided tours may allow viewing opportunities.

When observing nene, maintain a respectful distance—ideally at least 50 feet—and avoid sudden movements or loud noises. Never feed wildlife, as human food can harm their digestive systems and alter natural behaviors. Use binoculars or a telephoto lens for close-up views without disturbance.

Common Misconceptions About the Nene

Despite being widely recognized as Hawaii’s state bird, several misconceptions persist:

- Misconception: The nene is just a regular goose. Reality: While related to Canada geese, the nene is a distinct species with specialized adaptations to island life, including reduced webbing and terrestrial nesting habits.

- Misconception: It's commonly seen throughout all Hawaiian islands. Reality: Populations remain concentrated on Hawai‘i, Maui, and Moloka‘i, with only small, managed groups on O‘ahu and Kaua‘i.

- Misconception: The nene swims frequently like other geese. Reality: Though capable, the nene prefers dryland habitats and only visits water sources occasionally for drinking or cooling off.

Tips for Responsible Birdwatching in Hawaii

If you're planning a trip to spot the nene or other native birds such as the ‘apapane or ‘i‘iwi, consider these practical tips:

- Check seasonal patterns: Breeding season runs from September to March. During this time, nene are more territorial and visible near nest sites.

- Respect restricted zones: Some areas are closed during nesting months to prevent disturbance. Always follow posted signs and ranger instructions.

- Use quiet observation methods: Turn off car engines when scanning for birds and speak softly to minimize stress.

- Support conservation: Donate to local groups working on nene recovery or participate in citizen science projects like eBird to contribute data.

- Verify access details: Road conditions and visitor regulations vary by location and can change due to weather or volcanic activity. Check official park websites before visiting.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Why did Hawaii choose the nene as its state bird?

- Hawaii selected the nene in 1957 because it is a unique, endemic species that symbolizes the state’s rich biodiversity and cultural heritage. Its endangered status at the time also highlighted the need for conservation awareness.

- Is the nene found only in Hawaii?

- Yes, the nene is endemic to Hawaii, meaning it is naturally found nowhere else in the world. All wild populations exist exclusively within the Hawaiian Islands.

- Can the nene fly?

- Yes, the nene can fly, though it does so less frequently than many waterfowl. It uses flight primarily for escaping predators or moving between feeding and nesting areas.

- How can I help protect the nene?

- You can help by supporting habitat preservation initiatives, respecting wildlife viewing guidelines, reporting injured birds to authorities, and spreading awareness about its conservation needs.

- Are there any festivals or events celebrating the nene?

- While no major statewide festival focuses solely on the nene, environmental education programs during Hawaiian Goose Awareness Month (observed informally in November) promote its story through school activities and park talks.

In summary, understanding what is the state bird in Hawaii leads to a deeper appreciation of the nene—not just as a legal designation, but as a testament to ecological adaptation, cultural reverence, and ongoing conservation success. Whether you're researching for academic purposes, planning a birding adventure, or simply curious about Hawaiian symbols, the nene offers a compelling narrative of survival against the odds. By learning about its biology, history, and current challenges, we become better stewards of this irreplaceable part of Hawaii’s natural legacy.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4