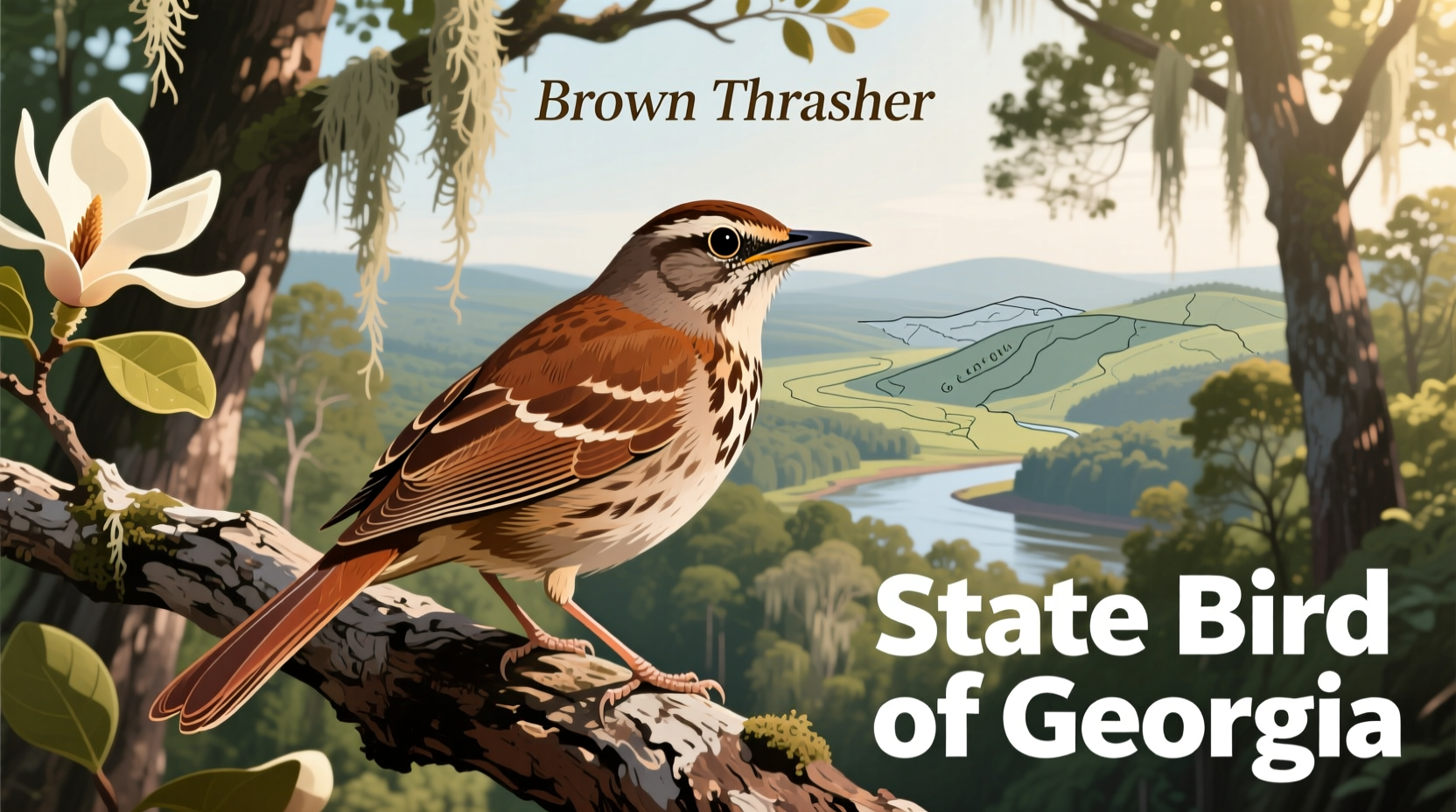

The state bird of Georgia is the brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum), a songbird known for its rich reddish-brown plumage, bold streaking, and remarkable vocal range. Officially designated in 1970, the brown thrasher stands as a symbol of Georgia’s natural heritage and ecological diversity. As one of the most frequently searched avian symbols in the southeastern United States, the state bird of Georgia captures both cultural pride and biological interest among residents, educators, and birdwatchers alike.

History and Designation of Georgia's State Bird

The journey to selecting the brown thrasher as Georgia’s official state bird began decades before its formal adoption. In 1928, the Georgia General Assembly considered several candidates, including the northern mockingbird and the cardinal, but no final decision was made at the time. It wasn’t until 1938 that the brown thrasher was informally recognized through a vote by schoolchildren, reflecting early public sentiment toward native wildlife.

However, it took more than three decades for this informal choice to become law. On March 20, 1970, Governor Lester Maddox signed House Bill 651, officially naming the brown thrasher the state bird of Georgia. This legislative act replaced the previous symbolic designation—the northern mockingbird—which had been adopted in 1928 but never formally codified. The clarification solidified the brown thrasher’s status and resolved longstanding confusion about Georgia’s avian emblem.

Why the Brown Thrasher Was Chosen

Several factors contributed to the selection of the brown thrasher as Georgia’s state bird. First and foremost is its prevalence throughout the state. Unlike migratory species that only pass through seasonally, the brown thrasher is a year-round resident across much of Georgia, commonly found in woodlands, suburban gardens, and thickets.

Beyond its abundance, the bird’s distinctive song played a significant role in its popularity. With over 1,100 recorded song types—more than any other North American bird—the brown thrasher exhibits extraordinary vocal complexity. Its habit of repeating phrases twice (“whisper-wing, whisper-wing, see-me, see-me”) makes it recognizable even to casual listeners. This musical talent resonated with Georgians who value tradition, expression, and regional identity.

Culturally, the brown thrasher embodies resilience and adaptability—traits often associated with the spirit of the South. Though shy and ground-foraging by nature, it fiercely defends its nest, sometimes dive-bombing intruders. This protective instinct mirrors values of family, home, and territorial pride deeply rooted in Southern culture.

Biological Profile: What Makes the Brown Thrasher Unique?

Scientifically classified as Toxostoma rufum, the brown thrasher belongs to the family Mimidae, which includes mockingbirds and catbirds. These birds are renowned for their mimicry abilities, and the brown thrasher is no exception. While not all of its songs are imitations, it frequently incorporates snippets of other birds’ calls into its lengthy, improvisational performances.

Physical Characteristics:

- Size: Approximately 9–11.5 inches (23–29 cm) long, with a wingspan of about 12 inches (30 cm)

- Weight: Around 2.1–3.1 ounces (60–89 grams)

- Coloration: Rich rufous-brown upperparts, pale underparts with heavy dark streaking, bright yellow eyes, and a long, curved bill ideal for probing leaf litter

- Flight Pattern: Undulating and low to the ground, often disappearing quickly into dense brush

The brown thrasher’s diet consists primarily of insects, spiders, snails, berries, and seeds. It uses its strong bill to sweep aside debris while foraging, making scratching sounds that can alert sharp-eared birdwatchers to its presence even when hidden from view.

Habitat and Distribution Across Georgia

Brown thrashers thrive in edge habitats—areas where forests meet open spaces such as fields, roadsides, or residential backyards. They prefer environments with ample shrub cover for nesting and protection. In Georgia, they are widespread from the coastal plains to the piedmont and lower mountain regions.

While present year-round, their activity levels vary seasonally. During spring and summer breeding months (April through July), males sing persistently from elevated perches like fence posts or treetops. In winter, they become quieter and more secretive, relying on dense vegetation for shelter against cold snaps and predators.

Urbanization has impacted some populations, but brown thrashers have shown adaptability to human-altered landscapes. Backyard bird feeders offering mealworms, suet, or cracked corn may attract them, especially during colder months. However, they tend to avoid highly manicured lawns lacking understory vegetation.

Conservation Status and Environmental Challenges

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the brown thrasher is currently listed as Least Concern. However, data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey indicate a moderate population decline since the 1960s—estimated at nearly 40% over five decades. Potential causes include habitat loss due to land development, pesticide use reducing insect prey, and increased predation by domestic cats.

In Georgia, conservation efforts focus on preserving mixed woodland edges and promoting native plant landscaping. Organizations like the Georgia Ornithological Society and the Atlanta Audubon Society advocate for responsible land management practices that support native bird species.

Individuals can contribute by minimizing chemical use in gardens, keeping outdoor cats indoors, and planting native shrubs such as blackberry, sumac, and hawthorn that provide food and shelter for brown thrashers.

How to Identify the Brown Thrasher: Tips for Birdwatchers

Spotting a brown thrasher requires patience and attention to behavioral cues. Here are practical tips for identifying this elusive songster:

- Listen for the Song: The most reliable way to detect a brown thrasher is by sound. Listen for long sequences of varied phrases, each repeated exactly twice. Compare it to the mockingbird, which repeats phrases three or more times and mimics a wider array of sounds.

- Look for Movement on the Ground: Watch leaf litter beneath bushes for rapid sweeping motions caused by the bird’s foraging behavior.

- Check for Physical Markings: Look for the long tail, curved bill, and heavily streaked breast. Distinguish it from the smaller, less streaked wood thrush or the uniformly gray catbird.

- Observe Nesting Behavior: Nests are typically built 3–5 feet off the ground in thorny shrubs. Both parents participate in feeding young, so repeated trips to a dense bush may signal a nearby nest.

Best times for observation are early morning hours during spring and late afternoon in fall. Use binoculars with close-focus capability to observe details without disturbing the bird.

Symbolism and Cultural Significance in Georgia

The brown thrasher holds deeper meaning beyond its biological traits. As Georgia’s official state bird, it appears on educational materials, license plates, and environmental campaigns. Schools often incorporate the bird into lessons about local ecology and civic symbols.

In literature and folklore, the thrasher represents vigilance and voice—its loud, complex songs interpreted as messages of warning or storytelling. Some Native American traditions associate brown-plumaged birds with earth energy and grounding, though specific tribal references to the brown thrasher are limited in historical records.

Interestingly, Emory University in Atlanta adopted the brown thrasher as its mascot, affectionately known as “Bill the Thrasher.” This reinforces the bird’s role as a symbol of intellectual curiosity and spirited defense—qualities admired in academic and athletic contexts.

Common Misconceptions About the State Bird

Despite its official status, several misconceptions persist about Georgia’s state bird:

- Misconception 1: “The northern mockingbird is Georgia’s state bird.” – False. Although once considered, the brown thrasher replaced it formally in 1970.

- Misconception 2: “Brown thrashers are rare.” – Incorrect. They are common across suitable habitats, though their secretive habits make them seem scarce.

- Misconception 3: “They migrate out of Georgia.” – Mostly false. Most individuals remain in the state year-round, especially in southern counties.

- Misconception 4: “It’s just another brown bird.” – Misleading. Among North American songbirds, few match its combination of size, vocal repertoire, and bold streaking.

Comparison with Other State Birds in the Southeast

Understanding Georgia’s choice becomes clearer when compared with neighboring states:

| State | State Bird | Year Adopted | Notable Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Georgia | Brown Thrasher | 1970 | Most song types of any bird; ground forager |

| Florida | Northern Mockingbird | 1927 | Master mimic; sings at night |

| Alabama | Northern Flicker (Yellowhammer) | 1927 | Woodpecker; Civil War nickname origin |

| Tennessee | Northern Mockingbird | 1933 | Dual state bird with Florida |

| South Carolina | Carolina Wren | 1948 | Loud singer despite small size |

This regional context highlights how each state emphasizes different aspects of avian life—from mimicry to historical symbolism—shaping unique identities through their official birds.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: When did Georgia officially adopt the brown thrasher as its state bird?

A: Georgia officially adopted the brown thrasher as its state bird on March 20, 1970.

Q: Does the brown thrasher migrate from Georgia?

A: Most brown thrashers in Georgia are non-migratory and remain in the state year-round, particularly in warmer southern areas.

Q: How can I attract brown thrashers to my backyard?

A: Provide dense shrubbery, leaf litter for foraging, and offer mealworms or suet in platform feeders placed near cover.

Q: Why is the brown thrasher called a 'thrasher'?

A: The name comes from its habit of vigorously thrashing through dead leaves and debris while searching for insects.

Q: Is the brown thrasher protected by law?

A: Yes, like all native birds in the U.S., it is protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, making it illegal to harm, capture, or possess them without a permit.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4