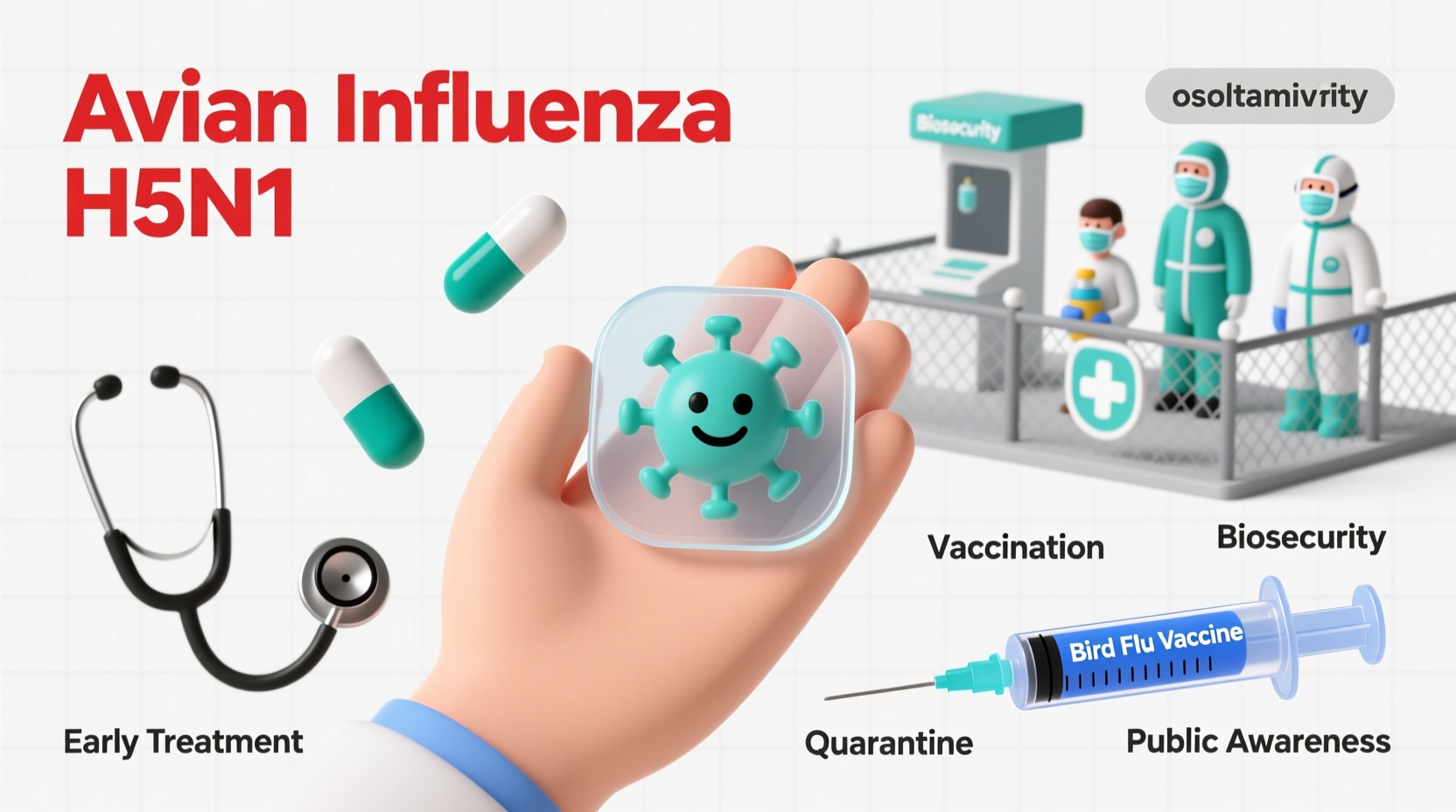

There is no specific cure for bird flu (avian influenza) in wild bird populations, and treatment primarily focuses on containment, prevention, and supportive care in domestic poultry and infected humans. A key strategy involves rapid culling of infected flocks to prevent the spread of the virus, combined with strict biosecurity measures such as disinfection of facilities, quarantine protocols, and movement restrictions—commonly referred to in agricultural circles as 'what is the treatment for bird flu outbreaks in commercial farms.' Antiviral medications like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) may be used in human cases exposed to infected birds, particularly during high-risk outbreaks. Vaccination of poultry is permitted in some countries but is not universally adopted due to concerns about virus surveillance and trade implications.

Understanding Bird Flu: The Biological Basis

Bird flu, or avian influenza, is caused by Type A influenza viruses that naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds, particularly ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, serving as reservoirs for transmission. The virus spreads through saliva, nasal secretions, and feces. While over a dozen subtypes exist, H5N1 and H7N9 are among the most pathogenic strains affecting both poultry and humans.

The virus can mutate rapidly, leading to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) strains that cause severe disease and high mortality in domestic birds such as chickens and turkeys. Unlike seasonal human flu, bird flu does not spread easily from person to person, but zoonotic transmission—when humans contract the virus directly from infected birds—is a serious public health concern.

Historical Context and Global Outbreaks

The first major outbreak of H5N1 was reported in Hong Kong in 1997, when 18 people were infected and six died. Since then, bird flu has re-emerged in multiple waves across Asia, Africa, Europe, and more recently, North and South America. In 2022 and 2023, an unprecedented global spread of H5N1 affected millions of commercial and backyard birds, prompting mass culling events and international travel advisories for live birds.

These recurring outbreaks highlight the limitations of current treatment strategies. Because there is no practical way to treat wild birds at scale, control relies heavily on monitoring migratory patterns, early detection via laboratory testing, and preemptive vaccination in certain regions. The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), along with national agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), coordinates global surveillance efforts.

Prevention Over Cure: Biosecurity Measures

Since effective treatment options are limited, especially in large-scale farming operations, prevention remains the cornerstone of managing bird flu. Key biosecurity practices include:

- Limiting access to poultry farms by visitors and vehicles

- Using dedicated clothing and footwear for farm workers

- Regular cleaning and disinfection of coops and equipment

- Isolating new or sick birds immediately

- Preventing contact between domestic flocks and wild birds

Farmers are encouraged to develop a biosecurity plan tailored to their operation. The USDA offers free resources and assessments through its Biosecurity for Birds program. In backyard settings, simple steps like covering feed storage and using netted enclosures can significantly reduce risk.

Vaccination: A Controversial Tool

Vaccination against avian influenza is permitted under WOAH guidelines but only as part of a comprehensive control strategy. Countries must report vaccinated flocks, as vaccines do not always prevent infection—they may only reduce symptoms and viral shedding. This complicates surveillance because vaccinated birds might still carry and transmit the virus silently.

Some nations, including China and parts of Southeast Asia, use preventive vaccination in poultry. Others, like the United States and most of the European Union, prefer a 'stamp-out' policy—rapid depopulation of infected flocks—because it allows for clearer disease tracking and facilitates international trade. Trade restrictions often follow confirmed outbreaks, making transparency crucial.

| Strategy | Used In | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Culling | USA, EU, Canada | Effective containment; clear disease status | Economically costly; animal welfare concerns |

| Vaccination + Surveillance | China, Egypt, Vietnam | Reduces mortality; protects livelihoods | Risk of undetected spread; trade barriers |

| Monitoring Only (Wild Birds) | Global | No intervention needed; ecological balance | No treatment possible; ongoing transmission risk |

Treatment in Humans: When Exposure Occurs

While bird flu does not spread efficiently between humans, those who work closely with infected poultry—farmers, veterinarians, slaughterhouse workers—are at higher risk. If exposure is suspected, antiviral drugs such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), or peramivir (Rapivab) may be prescribed prophylactically or therapeutically.

Early administration—within 48 hours of symptom onset—is critical for effectiveness. Symptoms in humans resemble severe influenza: high fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and in serious cases, pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anyone experiencing these symptoms after contact with sick or dead birds should seek medical attention immediately and inform healthcare providers of potential exposure.

Role of Wildlife and Migration Patterns

Migratory birds play a central role in the global dispersion of avian influenza. Species such as the bar-headed goose and ruddy shelduck travel thousands of miles annually, crossing continents and introducing the virus to new regions. Wetlands, stopover sites, and shared water sources become hotspots for inter-species transmission.

Ornithologists and epidemiologists collaborate to track outbreaks using satellite telemetry and genetic sequencing of virus samples collected from dead birds. Citizen scientists also contribute through programs like the USGS National Wildlife Health Center’s mortality reporting system. Reporting unusual bird deaths helps authorities respond quickly and implement localized control measures.

Public Awareness and Misconceptions

A common misconception is that eating properly cooked poultry or eggs can transmit bird flu. According to the CDC and WHO, this is false—avian influenza is destroyed at cooking temperatures above 165°F (74°C). However, handling raw infected meat or eggs poses a risk, so proper hygiene is essential.

Another myth is that pet birds are safe from infection. While indoor-only birds have low risk, outdoor aviaries or free-flight birds can be exposed, especially during migration seasons. Owners should stay informed about local outbreaks and avoid taking birds to public exhibitions if cases are reported nearby.

Regional Differences in Response Strategies

Responses to bird flu vary widely depending on economic structure, regulatory frameworks, and cultural attitudes toward poultry farming. In industrialized nations, centralized veterinary services enable rapid response and compensation for culled flocks. In contrast, smallholder farmers in developing countries may hesitate to report outbreaks due to fear of financial loss, delaying containment.

In Africa, limited diagnostic infrastructure slows confirmation of cases. In Latin America, recent detections in wild birds have prompted increased surveillance but not yet widespread culling. International cooperation is vital to ensure equitable access to diagnostics, vaccines, and technical support.

How to Stay Informed and Prepared

Whether you're a backyard chicken keeper, a wildlife enthusiast, or a traveler visiting rural areas, staying updated on bird flu activity is important. Reliable sources include:

- CDC Avian Influenza page

- World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) reports

- National agriculture department bulletins

- Local wildlife agencies

Downloadable apps and email alerts are available in many countries to notify the public of new outbreaks. Hunters should check state regulations before harvesting waterfowl, and birdwatchers are advised to avoid handling sick or dead birds and to clean binoculars and gear after outings.

Future Outlook and Research Directions

Scientists are exploring next-generation vaccines that offer broader protection across multiple strains. Universal flu vaccines, long a goal in human medicine, could eventually be adapted for poultry. Gene-editing technologies like CRISPR are being studied to develop birds resistant to influenza infection.

Improved surveillance using environmental sampling—testing water from ponds and lakes for viral RNA—offers promise for early warning systems. Integrating data from human, animal, and environmental health sectors (the 'One Health' approach) is increasingly seen as essential for preventing future pandemics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can bird flu be treated in chickens?

No, there is no approved treatment for bird flu in chickens. Infected flocks are typically euthanized to prevent further spread.

Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

There is no commercially available human vaccine for bird flu, but candidate vaccines are stockpiled by some governments for emergency use during outbreaks.

How do I protect my backyard flock?

Practice strict biosecurity: limit visitor access, keep feed secure, isolate new birds, and monitor for signs of illness such as decreased egg production or sudden death.

Can I get bird flu from watching wild birds?

No, simply observing birds from a distance poses no risk. Avoid touching sick or dead birds and wash hands after outdoor activities.

What should I do if I find a dead bird?

Do not handle it barehanded. Report it to your local wildlife agency or health department for testing, especially if multiple birds are found dead in the same area.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4