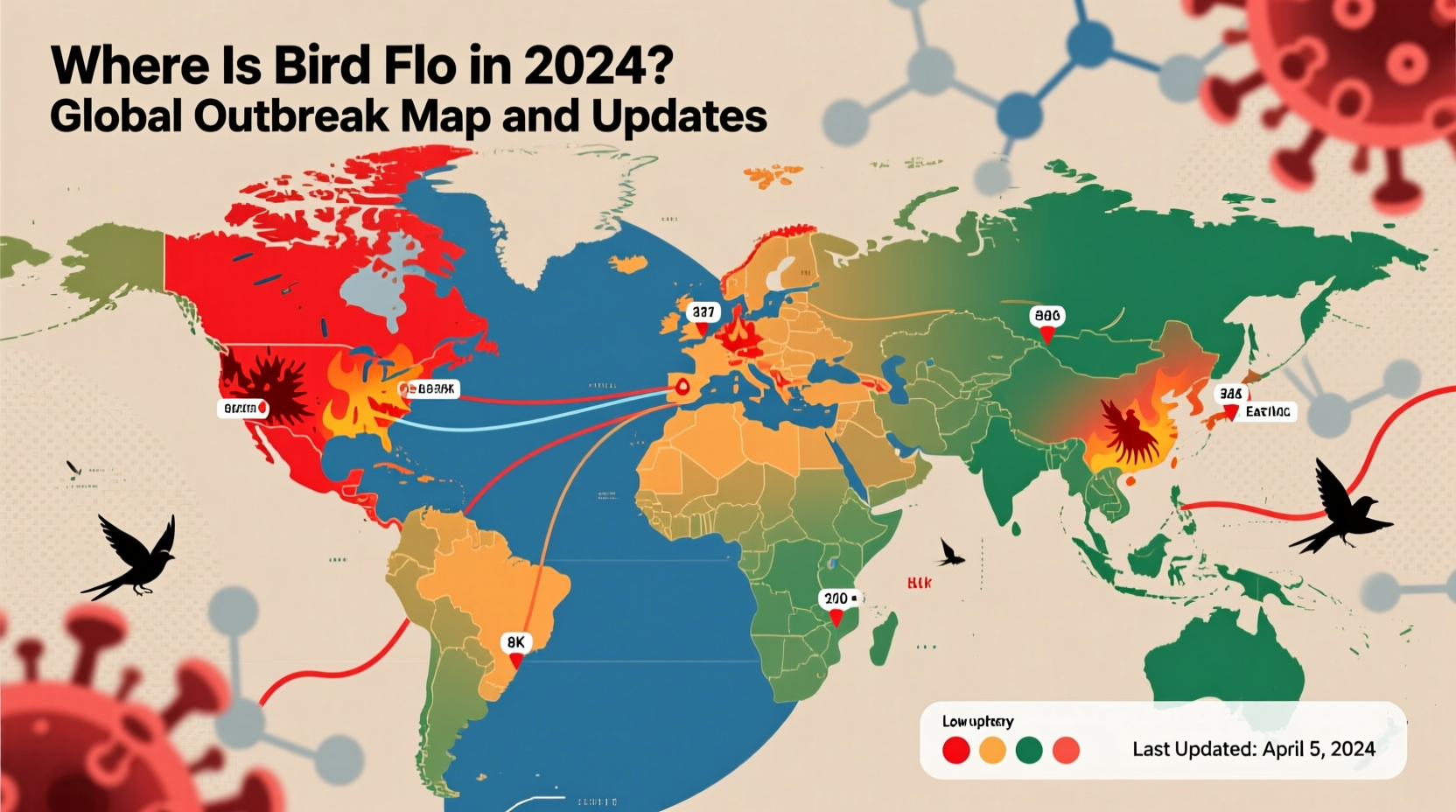

Bird flu, also known as avian influenza, is currently present in numerous regions across the globe, including parts of North America, Europe, and Asia. The virus primarily affects wild birds and poultry, with outbreaks reported in both commercial farms and backyard flocks. As of 2024, highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 remains widespread, particularly in migratory bird populations, which contribute to the geographic spread of where bird flu is active at any given time. Monitoring efforts by organizations such as the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) help track real-time data on where bird flu outbreaks are occurring.

Understanding Avian Influenza: Origins and Types

Avian influenza is caused by type A influenza viruses, which naturally circulate among wild aquatic birds like ducks, gulls, and shorebirds. These species often carry the virus without showing symptoms, making them silent carriers. There are many subtypes of avian influenza based on combinations of surface proteins—hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). The most concerning subtype in recent years has been H5N1, though others such as H7N9 and H5N8 have also caused significant outbreaks.

The first known identification of avian influenza dates back to the early 20th century, but it wasn’t until the late 1990s that global attention intensified following a fatal human case in Hong Kong linked to H5N1. Since then, the virus has evolved into multiple clades and strains, some of which have demonstrated increased transmissibility and pathogenicity in both birds and, occasionally, mammals—including humans.

Global Distribution of Bird Flu Outbreaks in 2024

In 2024, bird flu continues to be detected in over 60 countries. Key areas where bird flu is currently spreading include:

- North America: The United States and Canada have experienced widespread outbreaks in wild birds and commercial poultry operations, especially in the Midwest and Northeastern states.

- Europe: Countries such as Germany, France, the Netherlands, and the UK report seasonal spikes during fall and winter migration periods.

- Asia: China, India, Japan, and South Korea continue surveillance due to dense poultry farming and overlapping migratory flyways.

- Africa: Sporadic outbreaks occur in Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa, often linked to local trade and movement of domestic birds.

- South America: Limited but growing cases in countries like Chile and Argentina highlight southward expansion.

Data from WOAH’s WAHIS (World Animal Health Information System) shows that migratory patterns play a critical role in determining where bird flu appears seasonally. Spring and autumn migrations correlate strongly with new detections, especially along major flyways such as the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways in North America.

How Bird Flu Spreads: Transmission Pathways

The transmission of avian influenza occurs through several mechanisms:

- Direct contact between infected and healthy birds.

- Fecal-oral route: Virus shed in feces contaminates water sources or soil.

- Fomites: Equipment, clothing, vehicles, or footwear can carry the virus from one location to another.

- Airborne particles: In enclosed spaces like poultry houses, aerosolized virus may transmit short distances.

- Predation/scavenging: Mammals consuming infected birds have tested positive, raising concerns about cross-species transmission.

Notably, the current H5N1 strain has shown unusual behavior by infecting a range of non-avian species, including foxes, seals, sea lions, and even dairy cattle in the U.S., suggesting broader environmental persistence and adaptation potential.

Biological Impact on Birds and Poultry

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) causes severe illness and high mortality rates in domestic poultry such as chickens and turkeys. Symptoms include sudden death, decreased egg production, swelling of facial tissues, and neurological signs. In contrast, low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) may cause mild respiratory issues or go unnoticed.

Wild birds, particularly waterfowl, often survive infection but serve as reservoirs. This dual dynamic makes eradication extremely difficult. Once introduced into a commercial farm, entire flocks may require depopulation to prevent further spread—a devastating economic consequence for farmers.

| Region | Recent Outbreak Status (2024) | Primary Affected Species | Reporting Agency |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Widespread in wild birds; recurring poultry outbreaks | Ducks, geese, chickens, turkeys | USDA APHIS |

| European Union | Seasonal peaks during migration seasons | Wild waterfowl, farmed poultry | ECDC / EFSA |

| China | Ongoing surveillance; localized outbreaks | Chickens, ducks, pigeons | Ministry of Agriculture |

| Australia | No HPAI H5N1 detection in 2024 | Monitoring only | Department of Agriculture |

Human Risk and Public Health Implications

While bird flu does not easily spread from birds to humans, sporadic infections have occurred, usually among individuals with close contact with infected poultry. As of mid-2024, fewer than 900 human cases of H5N1 have been reported globally since 2003, with a fatality rate exceeding 50%. However, no sustained human-to-human transmission has been confirmed, which limits pandemic risk—for now.

Recent detections in U.S. dairy cattle and suspected cow-to-cow transmission have raised alarms. Two human cases were reported in 2024 linked to exposure to infected cattle, marking a shift in host range. Public health agencies emphasize vigilance, especially among agricultural workers, veterinarians, and those involved in live bird markets.

To reduce personal risk when visiting areas where bird flu is present:

- Avoid touching sick or dead birds.

- Wear gloves and masks when handling poultry.

- Cook poultry and eggs thoroughly (internal temperature ≥165°F).

- Report dead wild birds to local wildlife authorities.

Role of Migration in Determining Where Bird Flu Is Found

Migratory birds are central to understanding where bird flu spreads each year. Long-distance travelers follow established flyways, carrying the virus across continents. Satellite tracking studies show that ducks and shorebirds can transport the virus over thousands of miles, introducing it to new wetlands, farms, and urban parks.

Climate change may alter migration timing and routes, potentially affecting seasonal outbreak patterns. Warmer winters allow some birds to remain in northern latitudes longer, increasing local transmission windows. Additionally, habitat loss forces birds into closer proximity at remaining feeding sites, enhancing viral exchange.

Prevention and Biosecurity Measures

Effective prevention requires coordinated action at individual, farm, and national levels:

- Backyard flock owners: Keep birds indoors during outbreak alerts, secure feed from wild bird access, and quarantine new additions.

- Commercial farms: Implement strict biosecurity protocols, including vehicle disinfection, restricted personnel access, and routine testing.

- Government agencies: Fund surveillance programs, support rapid response teams, and promote international data sharing.

Vaccination remains controversial. While vaccines exist for certain strains, they do not always prevent infection or shedding, potentially masking disease presence. Some experts advocate for targeted vaccination in high-risk zones, while others stress stamping-out policies combined with improved monitoring.

Impact on Wildlife Conservation and Ecosystems

Bird flu poses a growing threat to endangered avian species. In 2023, mass die-offs were recorded in Caspian terns, common murres, and albatross colonies. Seabirds nesting in dense colonies are especially vulnerable due to rapid transmission. Similarly, raptors and scavengers may contract the virus by feeding on infected carcasses.

Conservationists urge caution in handling dead wildlife and recommend delaying relocation projects during active outbreaks. Protected areas are increasingly integrating disease surveillance into their management plans.

Where to Find Real-Time Information on Bird Flu Locations

For up-to-date information on where bird flu is currently detected, consult these authoritative sources:

- USDA APHIS Avian Influenza Page

- WOAH WAHIS Global Database

- ECDC Avian Influenza Surveillance

- CDC Avian Influenza Information

- FAO Global Framework for Controlling Avian Influenza

These platforms provide interactive maps, downloadable datasets, and weekly situation reports essential for researchers, farmers, and public health officials.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flu

Several myths persist about avian influenza:

- Myth: Eating chicken or eggs can give you bird flu.

Fact: Proper cooking destroys the virus. No human infections have been linked to properly prepared poultry products. - Myth: Only chickens get bird flu.

Fact: Over 100 bird species are susceptible, including songbirds, raptors, and waterfowl. - Myth: The virus is under control.

Fact: H5N1 is endemic in many wild bird populations and continues to evolve, requiring ongoing vigilance.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Is bird flu currently in the United States?

Yes, as of 2024, H5N1 is actively circulating in wild birds and has caused outbreaks in commercial and backyard poultry flocks across multiple states. - Can humans catch bird flu from wild birds?

Rarely. Most human cases involve direct, prolonged contact with infected poultry. Casual observation of wild birds poses negligible risk. - Are there travel restrictions due to bird flu?

No widespread travel bans exist, but travelers should avoid poultry farms and live bird markets in affected regions. - What should I do if I find a dead bird?

Do not touch it. Contact your local wildlife agency or health department for guidance on reporting and safe disposal. - Is there a vaccine for bird flu in humans?

A pre-pandemic H5N1 vaccine exists in limited supply for emergency use, but it is not available to the general public. Seasonal flu vaccines do not protect against avian influenza.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4