Birds fly primarily because flight allows them to efficiently escape predators, find food, migrate across vast distances, and access diverse habitats. The evolutionary adaptation of flight in birds—driven by lightweight skeletons, specialized feathers, and powerful pectoral muscles—enables behaviors such as seasonal migration, aerial foraging, and complex mating displays. Understanding why do birds fly reveals not only the biomechanics of avian wings but also the ecological and survival advantages that flight provides across species worldwide.

Evolutionary Origins of Avian Flight

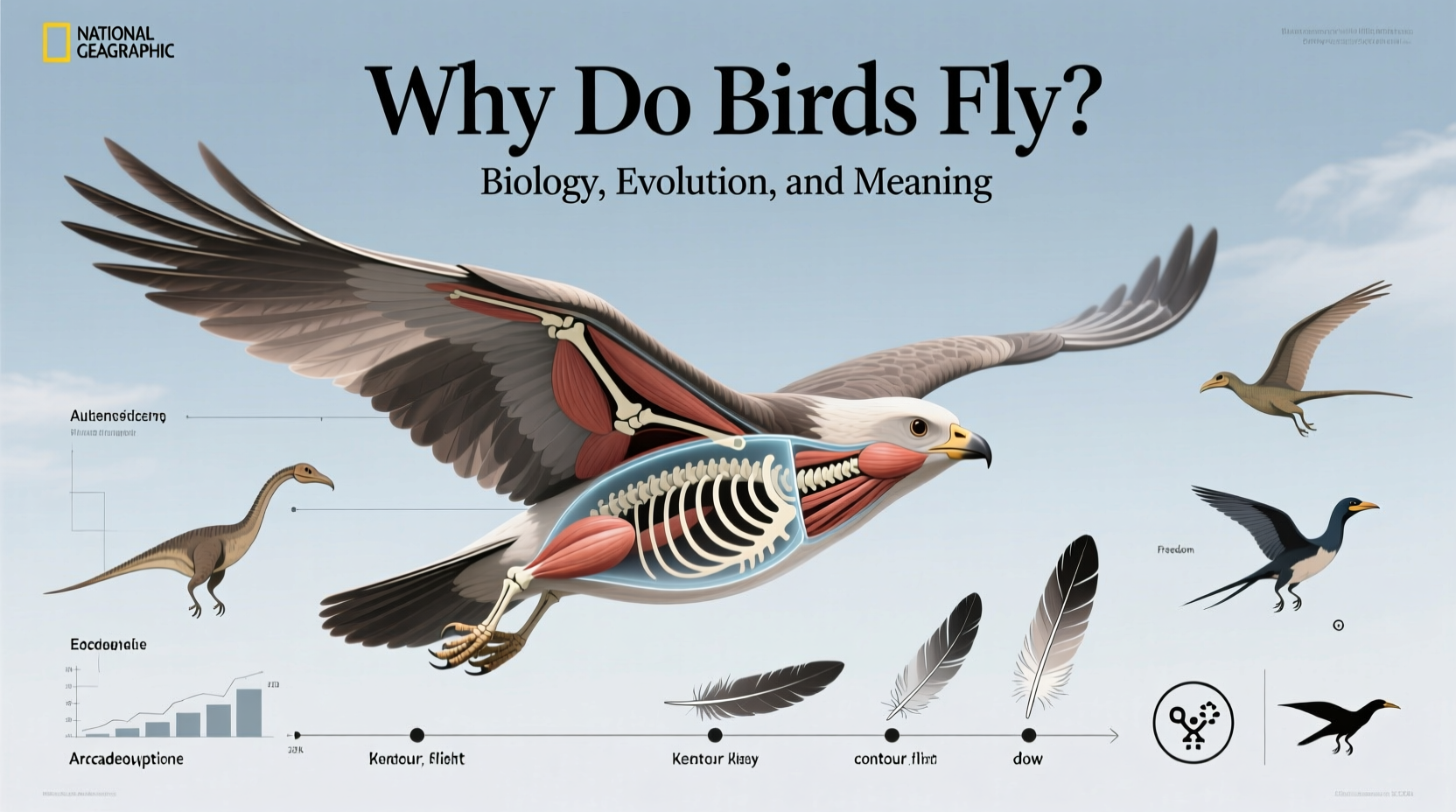

The ability to fly did not appear suddenly in birds but evolved over millions of years from small, feathered theropod dinosaurs. Fossils like Archaeopteryx, dating back approximately 150 million years, show a transitional form with both reptilian and avian features—teeth, a long bony tail, and feathered wings. Scientists debate two primary theories about how flight originated: the 'ground-up' hypothesis and the 'trees-down' hypothesis.

The ground-up theory suggests that running ancestors used flapping motions to gain lift while pursuing prey or escaping threats, gradually developing true flight. In contrast, the trees-down model proposes that gliding from elevated perches—such as tree branches—led to the evolution of powered flight. Evidence from modern bird development and fossil records supports elements of both, indicating that flight may have emerged through a combination of these behaviors.

Over time, natural selection favored anatomical changes that enhanced flight efficiency. Hollow bones reduced weight without sacrificing strength; fused skeletal structures increased rigidity during wingbeats; and the keeled sternum provided a large surface area for the attachment of flight muscles. These adaptations illustrate why do birds fly with such precision and endurance compared to other flying animals.

Anatomy Behind Bird Flight

The physical structure of birds is uniquely suited to flight. Key components include wings, feathers, respiratory systems, and musculature—all working in concert to generate lift, thrust, and control.

Bird wings are airfoils: their curved upper surface causes air to move faster above than below, creating lower pressure on top and generating lift. Wing shape varies significantly among species based on flight style. For example, albatrosses have long, narrow wings ideal for dynamic soaring over oceans, while hummingbirds possess short, rapidly beating wings allowing hovering and backward flight.

Feathers play a crucial role beyond insulation and display. Contour feathers streamline the body and form the wing surface, while down feathers provide warmth. During flight, asymmetrical flight feathers on the wings and tail help control direction and stability. Molting ensures worn feathers are replaced regularly, maintaining aerodynamic performance.

The avian respiratory system is highly efficient, featuring air sacs that allow continuous oxygen flow during both inhalation and exhalation. This supports the high metabolic demands of sustained flight. Additionally, birds have a four-chambered heart and rapid circulation, delivering oxygen-rich blood quickly to flight muscles.

Pectoralis major muscles power the downstroke, accounting for up to 25% of a bird’s body mass in strong fliers like pigeons. Supracoracoideus muscles enable the upstroke via a pulley-like tendon system beneath the shoulder joint—an arrangement unique to birds.

| Bird Species | Wing Shape | Flight Style | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bald Eagle | Broad, rounded | Soaring, gliding | Hunting, scavenging |

| Peregrine Falcon | Narrow, pointed | High-speed diving | Aerial predation |

| Hummingbird | Short, stiff | Hovering, agile | Flower feeding |

| Albatross | Long, slender | Dynamic soaring | Oceanic travel |

| Sparrow | Rounded | Flap-gliding | Short-distance movement |

Ecological and Behavioral Reasons Why Birds Fly

Flight offers birds unparalleled access to resources and safety mechanisms. One of the most significant reasons why do birds fly is migration—a behavior exhibited by nearly 40% of bird species. Each year, billions of birds undertake long-distance journeys between breeding and wintering grounds, often navigating thousands of miles using celestial cues, Earth's magnetic field, and landmarks.

Migratory patterns vary by region and species. Arctic Terns hold the record, traveling up to 44,000 miles annually between the Arctic and Antarctic. Such movements allow birds to exploit seasonal food abundance and avoid harsh climates. Bar-tailed Godwits make nonstop flights of over 7,000 miles across the Pacific Ocean, relying on fat stores and favorable winds.

Beyond migration, flight enables foraging flexibility. Hawks soar at high altitudes to spot prey, while swallows catch insects mid-air with acrobatic maneuvers. Some birds, like crows and jays, use flight to transport food to cached locations, enhancing survival during scarcity.

Escape from predators is another critical function. Ground-nesting birds such as plovers rely on sudden takeoffs to evade danger. Many species also use flight in social and reproductive contexts—male birds perform elaborate aerial displays to attract mates, as seen in sky-larking larks or courtship dives of Anna’s Hummingbirds.

Cultural and Symbolic Interpretations of Flight

Human fascination with bird flight spans cultures and centuries. Across mythologies, birds symbolize freedom, transcendence, and spiritual connection. In ancient Egypt, the Ba—a human-headed bird—represented the soul’s ability to journey between worlds. Native American traditions often view eagles as messengers between humans and the divine.

In literature and art, flight metaphorically represents aspiration and liberation. Icarus’ tragic attempt to fly toward the sun warns against hubris, yet his story underscores humanity’s enduring desire to conquer the skies. Modern idioms like “free as a bird” reflect deep-seated cultural associations between avian flight and personal freedom.

Religions incorporate birds as symbols of hope and renewal. Doves signify peace and the Holy Spirit in Christianity, while cranes represent longevity and wisdom in East Asian cultures. These symbolic meanings reinforce why do birds fly not just biologically, but within the human imagination—as embodiments of what lies beyond earthly limits.

Flightless Birds: Exceptions That Prove the Rule

Not all birds fly, which raises questions about when and why flight might be lost. Flightless birds—including ostriches, emus, kiwis, and penguins—evolved in environments with few terrestrial predators or where alternative survival strategies were more advantageous.

Ostriches, the largest living birds, inhabit African savannas where running at speeds up to 45 mph is more effective than flight for escaping predators. Their wings are used for balance and display rather than propulsion. Similarly, penguins traded aerial flight for underwater agility, using modified wings as flippers to 'fly' through water in pursuit of fish.

Island ecosystems often lead to flight loss due to isolation. The now-extinct dodo of Mauritius and New Zealand’s kakapo (a nocturnal parrot) evolved without mammalian predators, making energy-intensive flight unnecessary. However, human introduction of rats, cats, and dogs has made these species extremely vulnerable, highlighting how dependent flightless birds are on stable ecological conditions.

Genetically, flightlessness arises from mutations affecting muscle development, bone density, and feather structure. Yet even flightless birds retain vestigial features of their flying ancestors, such as small keels on the sternum or rudimentary wing bones, underscoring their shared evolutionary history with volant species.

Practical Tips for Observing Bird Flight

For birdwatchers and nature enthusiasts, observing flight patterns enhances identification and appreciation. Here are actionable tips:

- Learn Silhouettes: At a distance, wing shape and body profile are key identifiers. Raptors have broad wings and fan-shaped tails; swifts appear with sickle-shaped wings and minimal tails.

- Watch Flight Behavior: Does the bird flap continuously? Glide between flaps? Hover? Woodpeckers exhibit undulating flight, while swallows fly with erratic, sweeping motions.

- Note Timing: Migratory flights often occur at night. Using tools like radar ornithology apps (e.g., BirdCast) can reveal real-time migration intensity.

- Use Binoculars and Field Guides: Choose optics with wide fields of view for tracking fast-moving birds. Digital guides with audio calls aid recognition during flight.

- Visit Key Locations: Coastal headlands, mountain passes, and large lakes concentrate migrating birds. Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania and Cape May in New Jersey are renowned for fall raptor migrations.

Photographing flight requires fast shutter speeds (1/1000 sec or higher) and predictive autofocus. Practice panning techniques to capture sharp images of moving subjects.

Common Misconceptions About Bird Flight

Several myths persist about why birds fly. One common misconception is that all birds can fly. As discussed, around 60 extant species cannot. Another myth is that heavier birds shouldn’t be able to fly—yet swans and turkeys launch successfully due to powerful muscles and runway-like takeoffs.

Some believe birds fly south simply because it gets cold. In reality, food availability—not temperature alone—drives migration. Many ducks remain in northern regions if open water persists.

Another false idea is that birds migrate alone. While some do, many species travel in coordinated flocks, using V-formations to reduce drag and improve navigation. Geese honk to maintain group cohesion during flight.

FAQs About Why Birds Fly

Why do birds fly in flocks?

Birds fly in flocks for safety, navigation, and energy efficiency. The V-formation reduces wind resistance, allowing individuals to conserve energy during long migrations.

Do all birds migrate by flying?

No. Some migratory birds, like certain rail species, prefer walking or swimming over flying. Others, such as Emperor Penguins, migrate over ice on foot.

How do baby birds learn to fly?

Young birds develop flight skills through instinct and practice. Parents encourage fledglings to leave the nest, and repeated attempts strengthen muscles and coordination.

Can birds sleep while flying?

Yes, some seabirds like frigatebirds can sleep mid-flight using unihemispheric slow-wave sleep—one brain hemisphere rests while the other controls flight.

Why don't penguins fly?

Penguins lost the ability to fly as their wings adapted for swimming. Their dense bones and powerful pectoral muscles are optimized for diving, not aerial flight.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4