Yes, birds are reptiles in the context of modern biological classification. This may sound counterintuitive because we typically think of reptiles as cold-blooded, scaly animals like lizards and snakes, while birds are warm-blooded, feathered, and capable of flight. However, from an evolutionary and phylogenetic standpoint, birds are classified within the reptile group due to shared ancestry and genetic lineage. The long-held distinction between birds and reptiles has been redefined by advances in cladistics and molecular biology, leading scientists to conclude that birds are, in fact, a specialized subgroup of reptilesâspecifically, they are members of the dinosaur clade Theropoda. This makes the question 'are birds reptiles' not just scientifically valid but essential for understanding vertebrate evolution.

Evolutionary Origins: How Birds Descended from Dinosaurs

The idea that birds evolved from dinosaurs was first proposed in the 19th century after the discovery of Archaeopteryx in 1861âa fossil creature with both avian and reptilian features such as feathers and teeth. Over the past several decades, paleontological discoveries in China and elsewhere have provided overwhelming evidence linking birds directly to small, bipedal theropod dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Deinonychus.

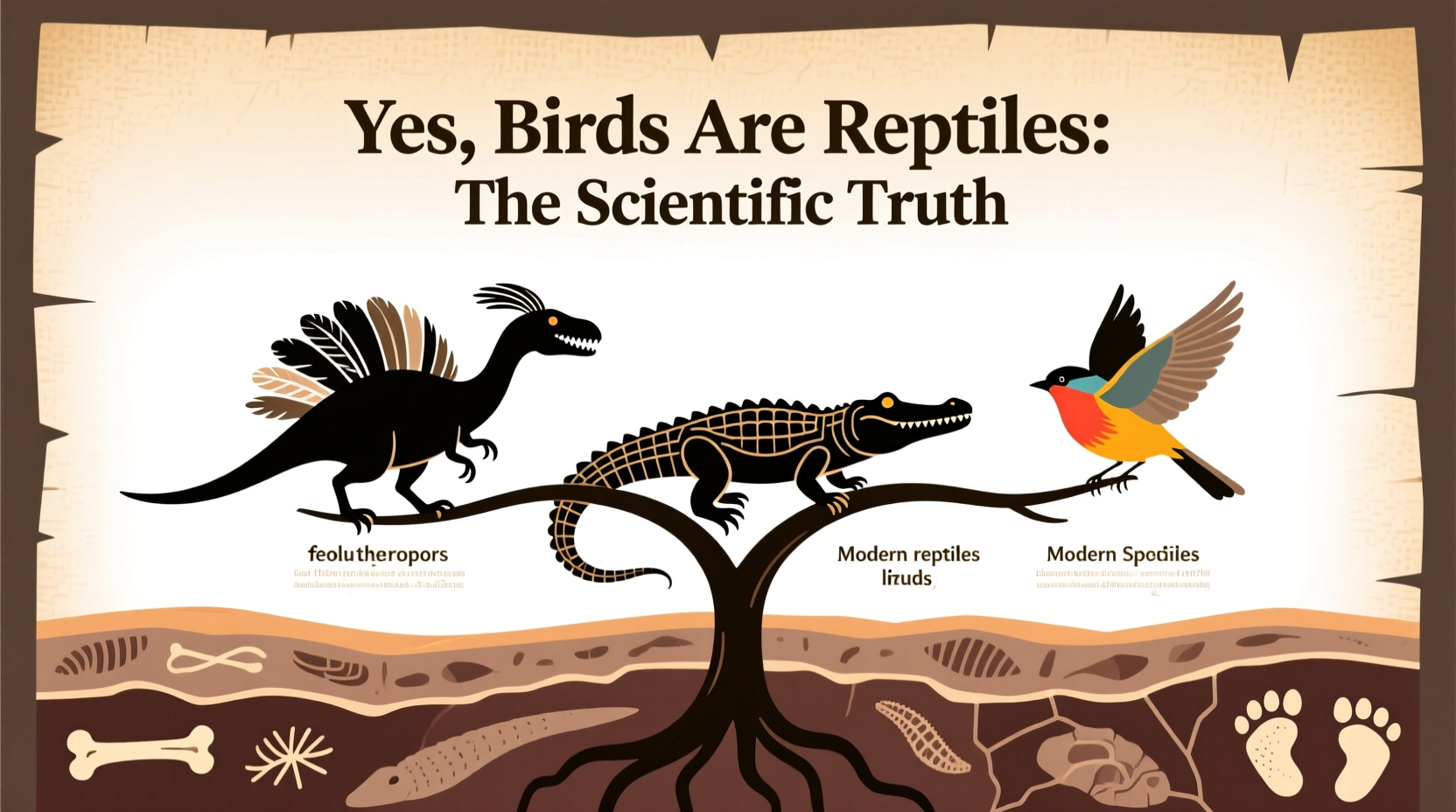

Modern phylogenetic taxonomy uses cladistics, which groups organisms based on common ancestry rather than physical traits alone. Under this system, any organism that descends from the most recent common ancestor of all reptilesâincluding crocodilians, turtles, lizards, snakes, and tuatarasâis considered part of Reptilia. Since birds share a more recent common ancestor with crocodiles than crocodiles do with lizards, birds are nested within the reptile clade. Therefore, when asking 'are birds reptiles according to evolutionary biology,' the answer is unequivocally yes.

Taxonomic Classification: Where Birds Fit in the Tree of Life

To understand why birds are reptiles, it's important to examine how biologists classify life today. Traditional Linnaean taxonomy separated birds (class Aves) from reptiles (class Reptilia), but modern systematics favors monophyletic groupsâclades that include an ancestor and all its descendants.

In this updated framework:

- Clade Sauropsida: Includes all modern reptiles and birds.

- Clade Archosauria: Includes crocodilians and birds (and their extinct relatives like pterosaurs and dinosaurs). \li>Clade Dinosauria: Birds fall under the subgroup Maniraptora within theropod dinosaurs.

This means that just as humans are mammalsâand more specifically primatesâbirds are reptiles and more specifically avian dinosaurs. Saying 'birds aren't reptiles' would be akin to saying 'bats aren't mammals' simply because they can fly.

Anatomical and Genetic Evidence Linking Birds to Reptiles

Beyond fossils, numerous anatomical and genetic similarities support the bird-reptile connection:

- Skeletal Structure: Birds retain many skeletal features seen in theropod dinosaurs, including hollow bones, a single middle ear bone, and a distinctive hip structure (three-pronged pelvis).

- Egg-Laying: Like reptiles, birds lay amniotic eggs with hard shells, a key trait of terrestrial vertebrates adapted to land reproduction.

- Genetic Markers: DNA studies show that birds share closer genetic sequences with crocodilians than with any other living non-avian reptile.

- Developmental Biology: Embryonic development in birds mirrors that of reptiles, particularly in early stages involving limb formation and organ layout.

Even behaviors like nest-building and parental care are observed in both birds and some reptiles (e.g., crocodile mothers guarding nests), further reinforcing evolutionary continuity.

Why the Misconception Persists: Cold-Blooded vs. Warm-Blooded Debate

One of the most persistent reasons people resist the idea that birds are reptiles is thermoregulation. Reptiles are traditionally described as ectothermic ('cold-blooded'), relying on external heat sources, whereas birds are endothermic ('warm-blooded'), generating internal body heat.

However, this distinction isn't absolute:

- Some reptiles exhibit regional endothermy (e.g., certain large tuna-like fish and even leatherback sea turtles maintain elevated body temperatures).

- Fossil evidence suggests that many non-avian dinosaurs may have had intermediate or even full endothermy.

- Endothermy likely evolved within the dinosaur lineage before modern birds appeared, meaning it arose within reptiles, not outside them.

Thus, being warm-blooded doesnât exclude birds from being reptilesâit simply shows that metabolic strategies can evolve within lineages. The presence of feathers, once thought unique to birds, has now been found in dozens of dinosaur species, blurring the line even further.

Cultural and Symbolic Perceptions of Birds vs. Reptiles

Culturally, birds and reptiles occupy vastly different symbolic spaces. Birds are often associated with freedom, spirituality, and transcendenceâthink of doves representing peace or eagles symbolizing national strength. In contrast, reptiles like snakes and crocodiles are frequently depicted as dangerous, sneaky, or primitive.

These cultural biases influence public perception and contribute to the reluctance to accept birds as reptiles. For example:

- In religious texts, birds are messengers (Noahâs dove), while serpents represent temptation.

- In mythology, phoenixes and thunderbirds signify rebirth and power, whereas dragonsâthough sometimes reveredâare often portrayed as monstrous.

- In children's media, birds are friendly protagonists; reptiles are villains or comic relief.

This symbolic divide reinforces the false notion that birds are fundamentally different from reptiles, despite scientific consensus to the contrary.

Implications for Birdwatching and Conservation

Understanding that birds are reptiles isn't just academicâit has real-world implications for conservation and ecological awareness. Recognizing birds as part of the larger reptilian lineage helps emphasize their vulnerability to environmental changes that also affect other reptiles.

For birdwatchers and naturalists, this knowledge enhances appreciation of avian diversity. When observing a red-tailed hawk soaring overhead, one might reflect that this animal is not merely 'like' a dinosaurâit is a dinosaur, in the same way that humans are apes.

Conservation efforts benefit from this unified perspective. Habitat loss, climate change, and pollution impact reptiles and birds similarly. Protecting wetlands helps herons and egrets (birds) as much as it does alligators and turtles (reptiles). Viewing these animals through an evolutionary lens fosters holistic ecosystem management.

Practical Tips for Observing Avian Reptiles in Nature

Whether you're a seasoned birder or new to wildlife observation, recognizing birds as reptiles can deepen your field experience. Here are practical tips:

- Visit Dinosaur-Rich Regions: Areas like the Morrison Formation (Western U.S.) or Liaoning Province (China) offer opportunities to learn about prehistoric ancestors while spotting modern birds in similar habitats.

- Compare Locomotion: Watch how birds walkâmany ground-dwelling species (e.g., roadrunners, ostriches) move with a horizontal spine posture reminiscent of dinosaurs.

- Observe Nesting Behavior: Look for birds building nests with vegetation and guarding youngâbehaviors mirrored in crocodilian parenting.

- Use Field Guides with Evolutionary Context: Choose guides that include evolutionary timelines or phylogenetic trees to better understand relationships between species.

- Attend Paleontology Exhibits: Museums with dinosaur-bird transition displays help visualize the link between T. rex and a sparrow.

Common Misunderstandings About Birds and Reptiles

Several myths persist about the relationship between birds and reptiles:

| Misconception | Scientific Reality |

|---|---|

| Birds evolved from reptiles. | Birds evolved within reptiles; they didn't come from reptiles as a separate groupâthey are reptiles. |

| Feathers make birds completely different. | Feathers evolved in non-avian dinosaurs; many had plumage but couldn't fly. |

| All reptiles are cold-blooded. | Body temperature regulation varies; some reptiles show warm-blooded traits, and birds inherited endothermy from dinosaur ancestors. |

| If birds are reptiles, shouldnât they have scales? | They do! Bird legs are covered in scutes (scaled skin), and feathers are modified scales at the genetic level. |

Frequently Asked Questions

- Are birds technically dinosaurs?

- Yes, birds are considered modern-day dinosaurs, specifically descended from small theropod dinosaurs. They are the only dinosaur lineage to survive the mass extinction 66 million years ago.

- If birds are reptiles, why are they in a separate class (Aves)?

- Class Aves is still used informally, but in modern cladistics, formal ranks like 'class' are less emphasized. Birds are nested within Reptilia phylogenetically, even if traditional classifications keep them separate.

- Do all scientists agree that birds are reptiles?

- The vast majority of evolutionary biologists and paleontologists accept this view based on fossil, genetic, and developmental evidence. It is the dominant position in peer-reviewed science.

- Does calling birds reptiles change how we protect them?

- It encourages integrated conservation strategies that recognize shared vulnerabilities among reptiles and birds, especially regarding habitat and climate threats.

- Can birds interbreed with reptiles?

- No. Despite shared ancestry, birds and non-avian reptiles diverged too far genetically to produce viable offspring. Reproductive isolation is expected after millions of years of evolution.

In conclusion, the answer to 'are birds reptiles' is a firm yes when viewed through the lens of evolutionary biology. While everyday language and traditional categories may separate birds from reptiles, science reveals a continuous lineage stretching back over 300 million years. Embracing this truth enriches our understanding of nature, deepens our respect for biodiversity, and reminds us that classification is not about appearancesâbut about ancestry.

浙公网安备

33010002000092号

浙公网安备

33010002000092号 浙B2-20120091-4

浙B2-20120091-4